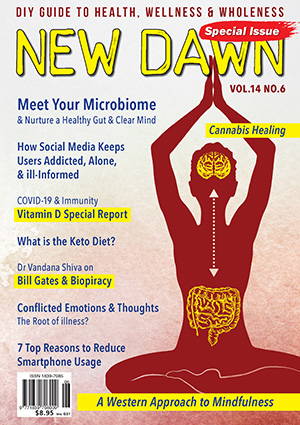

Bubbles of Hate: How Social Media Keeps Users Addicted, Alone, & Ill-Informed

BY DR TIM COLES

From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 14 No 6 (Dec 2020) Get the issue this article appears in

Get the issue this article appears in

Internet communication has gone from emails, messaging boards, and chatrooms, to sophisticated, all-pervasive networking. Social media companies build addictiveness into their products. The longer you spend on their sites and apps, the more data they generate. The more data, the more accurately they anticipate what you’ll do next and for how long. The better their predictions, the more money they make by selling your attention to advertisers.

Depressed and insecure about their value as human beings, the younger generations grow up knowing only digital imprisonment. Older users are trapped in polarised bubbles of political hate. As usual, the rich and powerful are the beneficiaries.

Masters of Manipulation

Humans are social animals. But big business wants us isolated, distracted, and susceptible to marketing. Using techniques based on classical conditioning, social media programmers bridge the gap between corporate profits and our need to communicate by keeping us simultaneously isolated and networked.

The Russian psychologist, Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936), pioneered research into conditioned reflexes, arguing that behaviour is rooted in the environment. His work was followed by the Americans John B. Watson (1878–1958) and B.F. Skinner (1904–90). Their often cruel conditioning experiments, conducted on animals and infants, laid the basis for gambling and advertising design. As early as the 1900s, slot machines were designed to make noises, like bell sounds, to elicit conditioned responses to keep the gambler fixed on the machine: just as Pavlov used a bell to condition his dogs to salivate. By the 1980s, slot machines had incorporated electronics to advantage particular symbols whilst giving the gambler the impression that they are near victory. “Stop buttons” gave the gambler the illusion of control. Sandy Parakilas, former Platform Operations Manager at Facebook, says: “Social media is very similar to a slot machine.”

Psychologist Watson’s experiments “set into motion industry-wide change” in TV, radio, billboard, and print advertising “that continued to develop until the present,” says historian Abby Bartholomew. Topics included emotional arousal in audiences (e.g., sexy actress → buy the product), brand loyalty (e.g., Disney is your family), and motivational studies (e.g., buy the product → look as good as this guy).

Many of these techniques involve stimulating so-called “feel good” chemicals like dopamine, endorphins, oxytocin, and serotonin. These are released when eating, exercising, having sex, and engaging in positive social interactions. Software designers learned that their release can be triggered by simple and unexpected things, like getting an email, being “friended,” seeing a retweet, and getting a like. The billionaire co-founder of Facebook and Napster, Sean Parker, said that the aim is to “give you a little dopamine hit every once in a while because someone liked or commented on a photo or a post.” But Parker also said of his company: “God only knows what it’s doing to our children’s brains.”

Facebook’s former Vice President of User Growth, Chamath Palihapitiya, doesn’t allow his children to use Facebook and says “we have created tools that are ripping apart the social fabric.” Tim Cook, the CEO of the world’s first trillion-dollar company Apple, on whose iPhones the addictions mainly occur, bluntly said of his young relatives: “I don’t want them on a social network.”

With the understanding that “the biggest companies in Silicon Valley have been in the business of selling their users” (technology investor, Roger McNamee), social media designers built upon the history of behaviourism and game addiction to keep users hooked. For example: In the good ol’ days, sites including the BBC and YouTube had page numbers (“pagination”), which gave users a sense of where they were in their search for an article or video. If the search results were poor, the user knew to skip to the last page and work backwards. But pages were phased out and replaced with “infinite scroll,” a feature designed in 2006 by Aza Raskin of Jawbone and Mozilla. Pagination, for instance, gives the user a stopping cue. Designers have systematically removed stopping cues. Likening infinite scroll to “behavioural cocaine,” Raskin said: “If you don’t give your brain time to catch up with your impulses, you just keep scrolling.”

With the understanding that “the biggest companies in Silicon Valley have been in the business of selling their users” (technology investor, Roger McNamee), social media designers built upon the history of behaviourism and game addiction to keep users hooked. For example: In the good ol’ days, sites including the BBC and YouTube had page numbers (“pagination”), which gave users a sense of where they were in their search for an article or video. If the search results were poor, the user knew to skip to the last page and work backwards. But pages were phased out and replaced with “infinite scroll,” a feature designed in 2006 by Aza Raskin of Jawbone and Mozilla. Pagination, for instance, gives the user a stopping cue. Designers have systematically removed stopping cues. Likening infinite scroll to “behavioural cocaine,” Raskin said: “If you don’t give your brain time to catch up with your impulses, you just keep scrolling.”

How They Do It & How It Hurts

Users think that they have control over their social media habits and the information being fed to them, including news and suggested webpages, are coming to them organically. But, unbeknownst to them, the framework is calculated. The US Deep State, for instance, helped to develop social networks. Sergey Brin and Larry Page developed their web crawling software, which they later turned into Google, with money from the US Defense Research Projects Agency. Referring to the Massive Digital Data Systems, the CIA-funded Dr Bhavani Thuraisingham confirmed that “[t]he intelligence community’s MDDS program essentially provided Brin seed-funding.”

Consider how the technologies were commercialised. “Growth” means advertising money accrued from sites visited, content browsed, links clicked, pages shared, etc. “Growth hackers” are described by former Google design ethicist Tristan Harris as “engineers whose job is to hack people’s psychology so they can get more growth.” Designers build applications into software that manipulate users’ unconscious behavioural cues to lead them in certain directions.

To give an example: The feel-good chemical oxytocin is released during positive social interactions. It is likely stimulated when social media companies send an email alert that family have shared a new photo. Other human foibles include novelty-seeking (for potential rewards) and temptation (fear of missing out or FOMO). These are linked to the feel-good chemical dopamine. Rather than including the new family photo in the email, the email is designed with a URL feature to tempt the user to click the link which directs them to the social media site in order to see the new photo. The chemical-reward response chain is as follows: family (oxytocin) → novelty/new photo (dopamine), temptation to click/FOMO → reward from positive social interaction after clicking and seeing the new photo (oxytocin-dopamine stimulation).

This convoluted chain of events is designed to sell the user’s attention to advertisers. The more time spent doing these things, the more adverts can be directed at the user and the more money for the social media company. Harris says “you are being programmed at a deeper level.”

In addition, tailored psychological profiles of users are secretly built, bought from, and sold to data brokers, like Experian. User behavioural patterns feed deep learning programmes which aim to predict the user’s next online move according to their personal tastes and previous browsing patterns. The more accurate the prediction, the more likely their attention is drawn to an advert and the more money social media firms accrue. Says former Mozilla’s Raskin: “They’re competing for your attention.” He asks: “How much of your life can we get you to give to us?”

Instagram was developed in 2010 by Facebook as a photo and video sharing service. It is used by a billion people globally and, unlike the teen-loving Snapchat, is used mainly by 18-44-year-olds. Instagram falls into the so-called “painkiller app” category. One designer explains that such apps “typically generate a stimulus, which usually revolves around negative emotions such as loneliness or boredom.”

Snapchat is a messaging app designed in 2011 that stores pictures (“Snaps”) for a short period of time. The app is used by 240 million people per day. Unlike YouTube, most of whose users are male, the majority of Snapchat users are female. Only 17 per cent of users are over 35. Its model is Snapstreak: a tracker that counts the days since the user replied to the Snap. Designers built FOMO (noted above) into Snapchat. The longer the user’s non-reply, the greater their credit score decline. This can lead to addiction because, unlike Facebook, Snapchat tags are “strong ties” (e.g., close friends, family), so the pressure to reply is greater.

In addition to the harmful content of social media – sexualised children, impossible and ever-changing beauty standards, cyberbullying, gaming addiction, loss of sleep, etc. – the very design of social media hurts young users. We all need to love ourselves and to feel loved by a small circle of others: friends, family, and partners. Young people are particularly susceptible to self-loathing and questioning whether someone loves them.

The introduction of social media has been devastating. A third of all teens who spend at least two hours a day on social media, i.e., the majority, have at least one suicide risk factor. The percentage increases to nearly half for those who spend five hours or more. A study of 14-year-olds found that those with fewer social media likes than their peers experienced depressive symptoms. Teens who are already victimised at school or within their peer-group were the worst-affected.

Divided & Conquered

Another feature built into social media is the polarisation of users along political lines; a phenomenon that mainly concerns people of voting age. One of the many human foibles exploited by social media designers is homophily: our love of things and people similar and familiar to us. Homophily makes us feel safe, understood, validated, and positively reinforced. It stimulates feel-good chemicals and, in social media contexts, is exploited to keep us inside an echo-chamber so that our biases are constantly reinforced, and we stay online for longer. But is this healthy?

Referring to Usenet group discussions, the lawyer Mike Godwin formulated the Rule of Hitler Analogies (or Godwin’s Law), which correctly posits that the longer an online discussion, the higher the probability that a user will compare others to Hitler. The formula was a reflection of users’ lack of tolerance toward the views of others.

A projection published in 2008 asked if people will be more tolerant due to the internet. Nearly six in 10 participants disagreed, compared to just three in 10 who agreed. In many ways, the industry specialists were fatalistic. Internet architect, Fred Baker of Cisco Systems, said: “Human nature will not have changed. There will be wider understanding of viewpoints, but tolerance of fundamental disagreement will not have improved.” Philip Lu of Wells Fargo Bank Internet Services said: “Just as social networking has allowed people to become more interconnected, this will also allow those with extreme views… to connect to their ‘kindred’ spirits.” Dan Larson of the PKD Foundation said: “The more open and free people are to pass on their inner feelings about things/people, especially under the anonymity of the Internet – will only foster more and more vitriol and bigotry.”

Users can artificially inflate their importance and the strength of their arguments by creating multiple accounts with different names (“sock puppets”). Some websites sell “followers” to boost users’ profiles. It is estimated that half of the Twitter followers of celebrities and politicians are bots. Gibberish-spewing algorithms have been programmed to write fake reviews on Amazon to hurt competitors’ sales. In at least one case, a pro-Israeli troll was unmasked posing as an anti-Semite in order to give the impression that anti-Semitism is rampant online and thus users should have more sympathy with Israel. Content creators increasingly find themselves de-platformed because of their political views while others’ social media accounts are suppressed by design (“shadow-banning”).

In the age of COVID, disinformation on both sides is spread: the severity of the disease, efficacy of vaccines, necessity of lockdowns, etc. As with US politics, Brexit, climate change, etc. neither side wants to talk rationally and open-mindedly with the other. The very designs of social media make this very difficult.

It should be emphasised that some social media are designed to create echo-chambers, and others are not. Cinelli et al. studied conversations about emotive subjects – abortion and vaccines – and found that while Facebook and Twitter show clear evidence of the echo-chamber effect, Reddit and Gab do not. Sasahara et al. demonstrate that due to users’ need for validation, when likes and friendships are withdrawn the network tends to descend into an echo-chamber.

Conclusion: What Can We Do?

Noted above is Google’s seed-funding from the Deep State. More recently, the ex-NSA contractor Edward Snowden revealed that Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and others were passing user data onto his former employer. Government and big tech became “the left hand and the right hand of the same body.” In the UK, the NSA worked with Government Communications Headquarters on the Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group. Leaks revealed an unprecedented, real-time surveillance and disruption operation that included hacking users’ social media accounts, posting content in their name, deleting their accounts, luring them into honey-traps, planting incriminating evidence on them, and more. To beat the antisocial social network, we need to remember who we are and what real communication is. We need to protect the young from the all-pervasive clutches of “social media” and to realise that we are being sold.Ask yourself: Do you use social media solely to organise protests, alert friends to alternative healing products, and spread anti-war messages? Or do you use it to send irrelevant information about your day-to-day habits in anticipation that an emoji or “like” will appear?Taking a step back can allow us to see outside and indeed prick the bubble of digital hatred in which the Deep State and corporate sectors have imprisoned us.

Noted above is Google’s seed-funding from the Deep State. More recently, the ex-NSA contractor Edward Snowden revealed that Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and others were passing user data onto his former employer. Government and big tech became “the left hand and the right hand of the same body.” In the UK, the NSA worked with Government Communications Headquarters on the Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group. Leaks revealed an unprecedented, real-time surveillance and disruption operation that included hacking users’ social media accounts, posting content in their name, deleting their accounts, luring them into honey-traps, planting incriminating evidence on them, and more. To beat the antisocial social network, we need to remember who we are and what real communication is. We need to protect the young from the all-pervasive clutches of “social media” and to realise that we are being sold.Ask yourself: Do you use social media solely to organise protests, alert friends to alternative healing products, and spread anti-war messages? Or do you use it to send irrelevant information about your day-to-day habits in anticipation that an emoji or “like” will appear?Taking a step back can allow us to see outside and indeed prick the bubble of digital hatred in which the Deep State and corporate sectors have imprisoned us.

Dr Tim Coles’s new book The War on You can be obtained from online booksellers & www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/B08HB68N97

Footnotes

1. Roger Collier (2008) Canadian Medical Association Journal, 179(1): 23-24

2. Quoted in Hilary Andersson, BBC Panorama, 3 July 2018, www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-44640959

3. Abby Bartholomew (2013) University of Nebraska, digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1042&context=journalismdiss

4. Quoted in Mike Allen, Axios, 9 November 2017, www.axios.com/sean-parker-unloads-on-facebook-god-only-knows-what-its-doing-to-our-childrens-brains-1513306792-f855e7b4-4e99-4d60-8d51-2775559c2671.html

5. Quoted in James Vincent, The Verge, 11 December 2017, www.theverge.com/2017/12/11/16761016/former-facebook-exec-ripping-apart-society

6. Quoted in Samuel Gibbs, Guardian, 19 January 2018, www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/jan/19/tim-cook-i-dont-want-my-nephew-on-a-social-network

7. Interviewed in The Social Dilemma (2020), Netflix.

8. Adam Alter (2017) Irresistible, London: Penguin

9. Quoted in Sean Keane, CNet, 4 July 2018, www.cnet.com/news/facebook-twitter-are-designed-to-be-like-behavioural-cocaine-for-users-insiders/

10. Quoted in Nafeez Ahmed, Insurge Intelligence, 22 January 2015, medium.com/insurge-intelligence/how-the-cia-made-google-e836451a959e

11. Interviewed in The Social Dilemma (2020), Netflix

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. J. Clement, Statista, 29 October 2020, www.statista.com/statistics/325587/instagram-global-age-group/

15. Quoted in Hannah Schwär & Qayyah Moynihan, Business Insider, 5 April 2020, www.businessinsider.com/facebook-has-been-deliberately-designed-to-mimic-addictive-painkillers-2018-12

16. J. Clement, Statista, 21 October 2020, www.statista.com/statistics/545967/snapchat-app-dau/

17. J. Clement, Statista, 29 October 2020, www.statista.com/statistics/933948/snapchat-global-user-age-distribution/

18. Sara Fischer, Axios, 17 October 2017, www.axios.com/teens-are-addicted-to-snapchat-1513306234-2b836b56-97c9-4b50-af8e-391fe68681ff.html

19. Leah Shafer, Usable Knowledge (Harvard), 15 December 2017, www.gse.harvard.edu/news/uk/17/12/social-media-and-teen-anxiety

20. Hae Yeon Lee et al. (2020) Child Development: DOI: 10.1111/cdev.13422

21. Rebecca Moore (2018) Nova Religio, 22(2): 145-54

22. All quoted in Janna Quitney Anderson and Lee Rainie, The Future of the Internet III, Pew Internet and American Life Project, 14 December 2008, pp. 38-46, www.pewresearch.org/internet/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/media/Files/Reports/2008/PIP_FutureInternet3.pdf

23. Caroline Forsey, HubSpot, 18 October 2020, blog.hubspot.com/marketing/buy-instagram-followers

24. Rand Fishkin, SparkToro, 9 October 2018, sparktoro.com/blog/we-analyzed-every-twitter-account-following-donald-trump-61-are-bots-spam-inactive-or-propaganda/

25. See my CounterPunch article, 4 October 2019, www.counterpunch.org/2019/10/04/robot-trolls-on-amazon-how-fake-reviews-could-undermine-progressive-politics/

26. Lance Tapley, Common Dreams, 20 August 2014, www.commondreams.org/hambaconeggs

27. Caroline Forsey, HubSpot, 27 August 2019, blog.hubspot.com/marketing/instagram-shadowban

28. Matteo Cinelli (2020) “Echo Chambers on Social Media: A comparative analysis,” arXiv:2004.09603

29. Kazutoshi Sasahara et al. (2020) Journal of Computational Social Science: link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s42001-020-00084-7.pdf

30. Quoted in Katie Collins, CNet, 4 November 2019, www.cnet.com/news/edward-snowden-says-facebook-amazon-and-google-engage-in-abuse/

21. JTRIG (2014) The Art of Deception: Training for a New Generation of Online Covert Operations, assets.documentcloud.org/documents/1021430/the-art-of-deception-training-for-a-new.pdf

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.

About the Author:

– Come Like Us on Facebook – Check us out on Instagram –

– Sign Up for our Newsletter –

Subscribe to our New NOW Youtube Channel

/www.newdawnmagazine.com

/www.newdawnmagazine.com