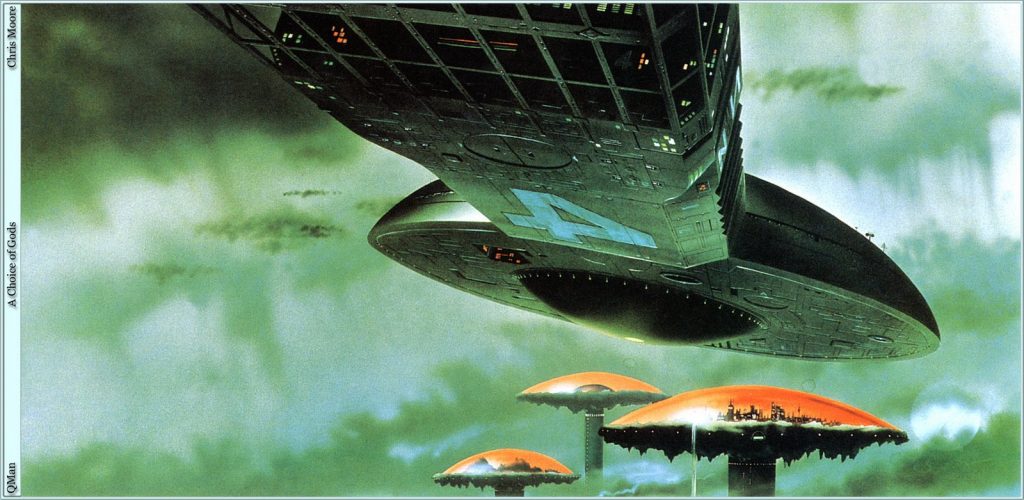

A CHOICE OF GODS

By Alan Floyd

If, like myself, you are a science fiction fan, a purveyor of the Golden Age era as well as an eager interceptor of all that’s new, then you may feel a little disillusioned with the kind of vistas the genre explores these days. And no matter how far reaching a science fiction story may seem, it’s ‘these days’ that are really being spoken of in their pages…(and film?). With the pendulum of story-line themes swinging steadfastly back from the Utopian to near-future Dystopia’s, (one can’t help but ask yourself) you may be coming to ask yourself ‘where now are those wild and wide open far reaches of adventure, opportunity and unbridled human potential?’

It seems now that the themes explored in the genre are driven more by the philosophy of materialism, with Atheistic undercurrents and the driving motivations of Darwinian natural selection. The wild, free and exploratory films and novels of the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s have morphed in the 90’s and beyond, into spectacles of social despair, seemingly driven by a need for realism and an adherence to the knotty labyrinths of hard and unyielding science.

But the science is wrong and those labyrinths are quite unnecessary.

In a more romantic era, when the genre itself had not yet even emerged onto the world scene; science, spiritualism, philosophy, art and the Alienists explorations of the mind, were categories all happily cross-pollinating in a Nineteenth Century stew from which the times ladled forth a Camille Flammarion or a Marie Corelli, or the lesser known but fantastical explorations of Jack London and Honore De Balzac. And not too long after all this, Olaf Stapledon and C.S. Lewis knocked a couple of Sci-Fi Fantasy epics right out of the ballpark.

In a more romantic era, when the genre itself had not yet even emerged onto the world scene; science, spiritualism, philosophy, art and the Alienists explorations of the mind, were categories all happily cross-pollinating in a Nineteenth Century stew from which the times ladled forth a Camille Flammarion or a Marie Corelli, or the lesser known but fantastical explorations of Jack London and Honore De Balzac. And not too long after all this, Olaf Stapledon and C.S. Lewis knocked a couple of Sci-Fi Fantasy epics right out of the ballpark.

Through all of this romantic traversing, ‘hither and yon’, across the inky dark reaches of outer space, the ‘man of God’ and soon to be ‘God-man’, were issues of vital and pressing concern. Our immanent evolution into something just beyond our ability to fully conceive, was a Question of the Moment, and burned into the literary psyche of the late 19th and early 20th Century.

Marie Corelli’s novels were a great example of this. With a writing career that began in the 1880’s and spanned more than fifty years, she was soon to become Queen Victoria’s favourite author. Old Queenie would request and have delivered the first copy of each new book she brought out, novels that were often florid Victorian science romances typical of what has now been dubbed “The radium Age” of science fiction. Concerns of immortality with the unlimited powers of will and imagination over the phenomenal world were the predominant themes in her work.

But my own journey back to such lost classics started with the discovery of an author whose name helped coin a term for science fiction of a truly cosmic, grand and breathtaking scale. That term, Stapledonian, refers to an early science fiction author by the name of Olaf Stapledon.

In Olaf Stapledon’s ‘Star-maker’, written in the early 1930’s, a protagonist having just had an argument with his wife is ‘all at a loss’, ‘out of sorts’, ‘spent’ you might say, and whilst laying down on a grassy hillside and looking up at the stars, just sort of drifts off into the cosmos. And I mean that in no figurative sense. Our hero is now an astral traveller, bouncing off ethereally through a star-spangled cosmos of wild adventure and conscious growth.

And perhaps we all know the feelings that brought him to this hillside. When life throws you a curve-ball you’ve maybe had reason to become familiar with a sense of total emotional surrender, lying back into something broader and loving, with a deep yearning for this as a fundamental truth of our lives. But the correlate explored in this book, the cosmic voyage in soul-form across vistas of time, space, and towards a conscious evolution of ultimate apotheosis, a universal Omega Point; well, it’s just for these possibilities that we really need an Olaf Stapledon. We need such stories as a clue to the greatness within.

In Camille Flammarion’s ‘Lumen’, written in the 1880’s, the protagonist, sending his detachable soul-form out again, travels the highways and bye-ways of the universe. Camille Flammarion’s fertile imagination here prefigured The general Theory of Relativity, in a book dubbed by some as the earliest work of science fiction. The fecundity of cosmic life envisioned here was the inspiration for Edgar Rice Burrough’s later works depicting the adventures of John Carter on Mars.

So here’s a mouthful of a new category for you, one that if you’re a science fiction fan you’ll really have to check out. ”Unaided Soul Flight through the Universe”. It seems that I’m stumbling upon more and more books that explore this very theme.

Another person who explored this idea from this same romantic epoch of unbridled creation was H.P. Lovecraft. In his short story ‘Beyond the Walls of Sleep’, a criminally insane protagonist has a higher and opposing self that is cast a long way adrift during his hours of slumber. This bead of light has a mission statement all it’s own. Drifting through the universe as a point of luminescence it rides the solar winds of the far reaches at the behest of purposes unknowable to it’s criminal, and conjoined, counterpart.

As for our soul-stuff being able to haul our lumpen earth-bound physiques to the stars- now that’s exiting. This idea has been explored in a number of science fiction classics as well. Alfred Bester’s ‘The Stars My Destination’, written in the 50’s and adapted loosely to film with ‘Jumper’ and leaving fans ever hopeful of a closer adaptation, explores the idea of ‘jaunting’, our newly evolved ability to blink in and out of existence and travel to any locale we want. And so, although this is just an Earth-side ability, our hero is the vanguard of a new leg in our evolution, cosmically furthering our reach.

Perhaps one of the most interesting sociological commentaries exploring this idea, Clifford Simak’s novel ‘A Choice of Gods’, posits the loss of a worldwide industrialism, with all its attendant manacles of mind forged materialism, as a freedom-giving impetus to again evolve this ability. Simak pursues this ultimate state of transcendence in many other works as well. In ‘Time is the Simplest Thing‘, an earlier work, spiritual evolution is still the name of the game.

These science fiction classics rarely make any mention of the chakras or higher energy centres. They speak, often with great eloquence, of the same idealized landscape, but it seems that occult lore and language just has to be absent. For all ‘serious’ reviewers contemplating these ghettoized writings their genre bending radical nature just can’t be seen to bend so far as to actually touch down in expressions of occultism. And that isolation perhaps has made of it an all too ready handmaiden to materialism. When the language of science, although supposedly neutral, can only express our culture’s growing cynicism, then the literature that uses it as a backbone can only grow ever more cynical in nature as well.

And so our choice of Gods, reflected in the science fiction of today, is materialism. As exciting and well-wrought as such Netflix creations as ‘Altered Carbon‘ are, they just seem carbon copied from an earlier time when the likes of Piers Anthony sent the soul, catalogued with Kirlian tracers of light, across the stars and into truly alien sleeves of flesh.

We are spirits in a material world, or so the old song would have it, and our science fiction visionaries used to reflect our potentials in consequence with fresh astonishment’s at every turn. Our worldview was hopeful. We recognized that we were energy beings, light caught in but a cosmic moment.

In the book ‘Cosmic Thunder‘ by William John Watkins, or the film ‘Snow’, staring Jeff Goldblum, we evolve. But by virtue of the atheistic and material minded battlefront upon which we cast these pearls of wisdom, we struggle. We struggle as a dispirited populace sold a false bill of goods. We yearn and hope against the marketing of fear. It truly seems that in the films, TV and literature of the fantastic in the last 30 years or so, we are doing that more and more- marketing fear.

Aliens invade instead of befriend, and society cracks as Zombies, contagion and Neo-Darwinism are sold to the young.

In ‘Seraphita’, Honore de Balzac, inspired by the occult writings of Emmanuel Swedenborg, imagines Seraphita, the main character, evolving on to the next stage of human development, an angel, a character taking on divine substance against the backdrop of the beautiful fjord-wrought coastal Norway.

That was his choice of Gods.

What’s yours?