Harvard Immunologist to Legislators: Unvaccinated Children Pose

ZERO Risk to Anyone

Dr. Tetyana Obukhanych

An Open Letter to Legislators Currently Considering Vaccine Legislation from Tetyana Obukhanych, PhD

Dear Legislator:

My name is Tetyana Obukhanych. I hold a PhD in Immunology. I am writing this letter in the hope that it will correct several common misperceptions about vaccines in order to help you formulate a fair and balanced understanding that is supported by accepted vaccine theory and new scientific findings.

Do unvaccinated children pose a higher threat to the public than the vaccinated?

It is often stated that those who choose not to vaccinate their children for reasons of conscience endanger the rest of the public, and this is the rationale behind most of the legislation to end vaccine exemptions currently being considered by federal and state legislators country-wide.

You should be aware that the nature of protection afforded by many modern vaccines – and that includes most of the vaccines recommended by the CDC for children – is not consistent with such a statement.

I have outlined below the recommended vaccines that cannot prevent transmission of disease either because they are not designed to prevent the transmission of infection (rather, they are intended to prevent disease symptoms), or because they are for non-communicable diseases.

People who have not received the vaccines mentioned below pose no higher threat to the general public than those who have, implying that discrimination against non-immunized children in a public school setting may not be warranted.

- IPV (inactivated poliovirus vaccine) cannot prevent transmission of poliovirus. (see appendix for the scientific study, Item #1). Wild poliovirus has been non-existent in the USA for at least two decades. Even if wild poliovirus were to be re-imported by travel, vaccinating for polio with IPV cannot affect the safety of public spaces. Please note that wild poliovirus eradication is attributed to the use of a different vaccine, OPV or oral poliovirus vaccine. Despite being capable of preventing wild poliovirus transmission, use of OPV was phased out long ago in the USA and replaced with IPV due to safety concerns.

- Tetanus is not a contagious disease, but rather acquired from deep-puncture wounds contaminated with C. tetani spores. Vaccinating for tetanus (via the DTaP combination vaccine) cannot alter the safety of public spaces; it is intended to render personal protection only.

- While intended to prevent the disease-causing effects of the diphtheria toxin, the diphtheria toxoid vaccine (also contained in the DTaP vaccine) is not designed to prevent colonization and transmission of C. diphtheriae. Vaccinating for diphtheria cannot alter the safety of public spaces; it is likewise intended for personal protection only.

- The acellular pertussis (aP) vaccine (the final element of the DTaP combined vaccine), now in use in the USA, replaced the whole cell pertussis vaccine in the late 1990s, which was followed by an unprecedented resurgence of whooping cough. An experiment with deliberate pertussis infection in primates revealed that the aP vaccine is not capable of preventing colonization and transmission of B. pertussis. The FDA has issued a warning regarding this crucial finding. [1]

Furthermore, the 2013 meeting of the Board of Scientific Counselors at the CDC revealed additional alarming data that pertussis variants (PRN-negative strains) currently circulating in the USA acquired a selective advantage to infect those who are up-to-date for their DTaP boosters, meaning that people who are up-to-date are more likely to be infected, and thus contagious, than people who are not vaccinated.

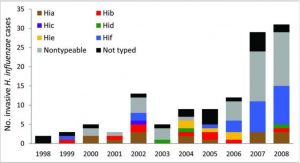

- Among numerous types of H. influenzae, the Hib vaccine covers only type b. Despite its sole intention to reduce symptomatic and asymptomatic (disease-less) Hib carriage, the introduction of the Hib vaccine has inadvertently shifted strain dominance towards other types of H. influenzae (types a through f). These types have been causing invasive disease of high severity and increasing incidence in adults in the era of Hib vaccination of children (see appendix for the scientific study, Item #4). The general population is more vulnerable to the invasive disease now than it was prior to the start of the Hib vaccination campaign. Discriminating against children who are not vaccinated for Hib does not make any scientific sense in the era of non-type b H. influenzae disease.

- Hepatitis B is a blood-borne virus. It does not spread in a community setting, especially among children who are unlikely to engage in high-risk behaviors, such as needle sharing or sex. Vaccinating children for hepatitis B cannot significantly alter the safety of public spaces. Further, school admission is not prohibited for children who are chronic hepatitis B carriers. To prohibit school admission for those who are simply unvaccinated – and do not even carry hepatitis B – would constitute unreasonable and illogical discrimination.

In summary, a person who is not vaccinated with IPV, DTaP, HepB, and Hib vaccines due to reasons of conscience poses no extra danger to the public than a person who is. No discrimination is warranted.

How often do serious vaccine adverse events happen?

“It is often stated that vaccination rarely leads to serious adverse events.

Unfortunately, this statement is not supported by science.”

A recent study done in Ontario, Canada, established that vaccination actually leads to an emergency room visit for 1 in 168 children following their 12-month vaccination appointment and for 1 in 730 children following their 18-month vaccination appointment (see appendix for a scientific study, Item #5).

When the risk of an adverse event requiring an ER visit after well-baby vaccinations is demonstrably so high, vaccination must remain a choice for parents, who may understandably be unwilling to assume this immediate risk in order to protect their children from diseases that are generally considered mild or that their children may never be exposed to.

Can discrimination against families who oppose vaccines for reasons of conscience prevent future disease outbreaks of communicable viral diseases, such as measles?

Measles research scientists have for a long time been aware of the “measles paradox.” I quote from the article by Poland & Jacobson (1994) “Failure to Reach the Goal of Measles Elimination: Apparent Paradox of Measles Infections in Immunized Persons.” Arch Intern Med 154:1815-1820:

“The apparent paradox is that as measles immunization rates rise to high levels in a population, measles becomes a disease of immunized persons.” [2]

Further research determined that behind the “measles paradox” is a fraction of the population called LOW VACCINE RESPONDERS. Low-responders are those who respond poorly to the first dose of the measles vaccine. These individuals then mount a weak immune response to subsequent RE-vaccination and quickly return to the pool of “susceptibles’’ within 2-5 years, despite being fully vaccinated. [3]

Re-vaccination cannot correct low-responsiveness: it appears to be an immuno-genetic trait. [4] The proportion of low-responders among children was estimated to be 4.7% in the USA. [5]

Studies of measles outbreaks in Quebec, Canada, and China attest that outbreaks of measles still happen, even when vaccination compliance is in the highest bracket (95-97% or even 99%, see appendix for scientific studies, Items #6&7). This is because even in high vaccine responders, vaccine-induced antibodies wane over time. Vaccine immunity does not equal life-long immunity acquired after natural exposure.

It has been documented that vaccinated persons who develop breakthrough measles are contagious. In fact, two major measles outbreaks in 2011 (in Quebec, Canada, and in New York, NY) were re-imported by previously vaccinated individuals. [6] [7]

Taken together, these data make it apparent that elimination of vaccine exemptions, currently only utilized by a small percentage of families anyway, will neither solve the problem of disease resurgence nor prevent re-importation and outbreaks of previously eliminated diseases.

Is discrimination against conscientious vaccine objectors the only practical solution?

The majority of measles cases in recent US outbreaks (including the recent Disneyland outbreak) are adults and very young babies, whereas in the pre-vaccination era, measles occurred mainly between the ages 1 and 15.

Natural exposure to measles was followed by lifelong immunity from re-infection, whereas vaccine immunity wanes over time, leaving adults unprotected by their childhood shots. Measles is more dangerous for infants and for adults than for school-aged children.

Despite high chances of exposure in the pre-vaccination era, measles practically never happened in babies much younger than one year of age due to the robust maternal immunity transfer mechanism.

The vulnerability of very young babies to measles today is the direct outcome of the prolonged mass vaccination campaign of the past, during which their mothers, themselves vaccinated in their childhood, were not able to experience measles naturally at a safe school age and establish the lifelong immunity that would also be transferred to their babies and protect them from measles for the first year of life.

Luckily, a therapeutic backup exists to mimic now-eroded maternal immunity. Infants as well as other vulnerable or immunocompromised individuals, are eligible to receive immunoglobulin, a potentially life-saving measure that supplies antibodies directed against the virus to prevent or ameliorate disease upon exposure (see appendix, Item #8).

In summary:

1) due to the properties of modern vaccines, non-vaccinated individuals pose no greater risk of transmission of polio, diphtheria, pertussis, and numerous non-type b H. influenzae strains than vaccinated individuals do, non-vaccinated individuals pose virtually no danger of transmission of hepatitis B in a school setting, and tetanus is not transmissible at all;

2) there is a significantly elevated risk of emergency room visits after childhood vaccination appointments attesting that vaccination is not risk-free;

3) outbreaks of measles cannot be entirely prevented even if we had nearly perfect vaccination compliance; and

4) an effective method of preventing measles and other viral diseases in vaccine-ineligible infants and the immunocompromised, immunoglobulin, is available for those who may be exposed to these diseases.

Taken together, these four facts make it clear that discrimination in a public school setting against children who are not vaccinated for reasons of conscience is completely unwarranted as the vaccine status of conscientious objectors poses no undue risk to the public.

Sincerely Yours,

~ Tetyana Obukhanych, PhD

Tetyana Obukhanych earned her Ph.D. in Immunology at the Rockefeller University, New York, NY with her research dissertation focused on immunologic memory. She was subsequently involved in laboratory research as a postdoctoral research fellow at Harvard Medical School and Stanford University School of Medicine, before fully devoting herself to natural parenting.

(Original Source: legislature.vermont.gov – Testimony Senate Health & Welfare Committee Wednesday April 22, 2015 H.98 – public records)

Editor’s Note: This article has been slighted edited to reflect the language from the letter submitted to the Vermont General Assembly on April 22, 2015. As part of the Vermont Senate Health & Welfare Committee, it is a matter of public record and accessible here.)

UPDATE: The above links on the Vermont government website no longer work. Here is a copy.

Comment on this article at VaccineImpact.com.

Appendix

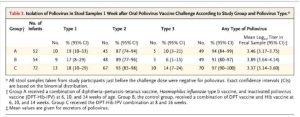

Item #1. The Cuba IPV Study collaborative group. (2007) Randomized controlled trial of inactivated poliovirus vaccine in Cuba. N Engl J Med 356:1536-44

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17429085

The table below from the Cuban IPV study documents that 91% of children receiving no IPV (control group B) were colonized with live attenuated poliovirus upon deliberate experimental inoculation. Children who were vaccinated with IPV (groups A and C) were similarly colonized at the rate of 94-97%. High counts of live virus were recovered from the stool of children in all groups. These results make it clear that IPV cannot be relied upon for the control of polioviruses.

Item #2. Warfel et al. (2014) Acellular pertussis vaccines protect against disease but fail to prevent infection and transmission in a nonhuman primate model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:787-92

Item #2. Warfel et al. (2014) Acellular pertussis vaccines protect against disease but fail to prevent infection and transmission in a nonhuman primate model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:787-92

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24277828

“Baboons vaccinated with aP were protected from severe pertussis-associated symptoms but not from colonization, did not clear the infection faster than naïve [unvaccinated] animals, and readily transmitted B. pertussis to unvaccinated contacts. By comparison, previously infected [naturally-immune] animals were not colonized upon secondary infection.”

Item #3. Meeting of the Board of Scientific Counselors, Office of Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Tom Harkins Global Communication Center, Atlanta, Georgia, December 11-12, 2013

http://www.cdc.gov/maso/facm/pdfs/BSCOID/2013121112_BSCOID_Minutes.pdf

Resurgence of Pertussis (p.6)

“Findings indicated that 85% of the isolates [from six Enhanced Pertussis Surveillance Sites and from epidemics in Washington and Vermont in 2012] were PRN-deficient and vaccinated patients had significantly higher odds than unvaccinated patients of being infected with PRN-deficient strains. Moreover, when patients with up-to-date DTaP vaccinations were compared to unvaccinated patients, the odds of being infected with PRN-deficient strains increased, suggesting that PRN-bacteria may have a selective advantage in infecting DTaP-vaccinated persons.”

Item #4. Rubach et al. (2011) Increasing incidence of invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease in adults, Utah, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 17:1645-50

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21888789

The chart below from Rubach et al. shows the number of invasive cases of H. influenzae (all types) in Utah in the decade of childhood vaccination for Hib.

Item #5. Wilson et al. (2011) Adverse events following 12 and 18 month vaccinations: a population-based, self-controlled case series analysis. PLoS One 6:e27897

Item #5. Wilson et al. (2011) Adverse events following 12 and 18 month vaccinations: a population-based, self-controlled case series analysis. PLoS One 6:e27897

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22174753

“Four to 12 days post 12 month vaccination, children had a 1.33 (1.29-1.38) increased relative incidence of the combined endpoint compared to the control period, or at least one event during the risk interval for every 168 children vaccinated. Ten to 12 days post 18 month vaccination, the relative incidence was 1.25 (95%, 1.17-1.33) which represented at least one excess event for every 730 children vaccinated. The primary reason for increased events was statistically significant elevations in emergency room visits following all vaccinations.”

Item #6. De Serres et al. (2013) Largest measles epidemic in North America in a decade–Quebec, Canada, 2011: contribution of susceptibility, serendipity, and superspreading events. J Infect Dis 207:990-98

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23264672

“The largest measles epidemic in North America in the last decade occurred in 2011 in Quebec, Canada.”

“A super-spreading event triggered by 1 importation resulted in sustained transmission and 678 cases.”

“The index case patient was a 30-39-year old adult, after returning to Canada from the Caribbean. The index case patient received measles vaccine in childhood.”

“Provincial [Quebec] vaccine coverage surveys conducted in 2006, 2008, and 2010 consistently showed that by 24 months of age, approximately 96% of children had received 1 dose and approximately 85% had received 2 doses of measles vaccine, increasing to 97% and 90%, respectively, by 28 months of age. With additional first and second doses administered between 28 and 59 months of age, population measles vaccine coverage is even higher by school entry.”

“Among adolescents, 22% [of measles cases] had received 2 vaccine doses. Outbreak investigation showed this proportion to have been an underestimate; active case finding identified 130% more cases among 2-dose recipients.”

Item #7. Wang et al. (2014) Difficulties in eliminating measles and controlling rubella and mumps: a cross-sectional study of a first measles and rubella vaccination and a second measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination. PLoS One 9:e89361

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24586717

“The reported coverage of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine is greater than 99.0% in Zhejiang province. However, the incidence of measles, mumps, and rubella remains high.”

Item #8. Immunoglobulin Handbook, Health Protection Agency

HUMAN NORMAL IMMUNOGLOBULIN (HNIG):

Indications

- To prevent or attenuate an attack in immuno-compromised contacts

- To prevent or attenuate an attack in pregnant women

- To prevent or attenuate an attack in infants under the age of 9 months

Footnotes

[1] http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm376937.htm

(Edited to add: Apparently, the FDA pulled the above link, but the content is archived here: https://web.archive.org/web/20131130004447/https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm376937.htm)

[2] http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=619215

[3] Poland (1998) Am J Hum Genet 62:215-220

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9463343

“ ‘poor responders,’ who were re-immunized and developed poor or low-level antibody responses only to lose detectable antibody and develop measles on exposure 2–5 years later.”

[4] ibid

“Our ongoing studies suggest that seronegativity after vaccination [for measles] clusters among related family members, that genetic polymorphisms within the HLA [genes] significantly influence antibody levels.”

[5] LeBaron et al. (2007) Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161:294-301

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17339511

“Titers fell significantly over time [after second MMR] for the study population overall and, by the final collection, 4.7% of children were potentially susceptible.”

[6] De Serres et al. (2013) J Infect Dis 207:990-998

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23264672

“The index case patient received measles vaccine in childhood.”

[7] Rosen et al. (2014) Clin Infect Dis 58:1205-1210

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24585562

“The index patient had 2 doses of measles-containing vaccine.”