How BlackRock Conquered the World —

Part 2 GOING DIRECT

by James Corbett

corbettreport.com

November 19, 2022

If you read Part 1 of the How BlackRock Conquered the World series, you will know how BlackRock went from an obscure investment firm in the 1980s to one of the most powerful asset managers in the world after the Global Financial Crisis of 2007—2008. You will also know how BlackRock’s CEO, Larry Fink, wasted no time in using the company’s immense riches—with over $10 trillion under management and a position as one of the top three institutional investors in seemingly every Fortune 500 company—to gain political power.

But Fink and his lackeys were not interested in accruing power merely for its own sake. No, the point of getting power is to use it. So the question is: how did they use this newly acquired political power?

Well, did you hear about a little thing called the COVID-19 pandemic? If you’re reading The Corbett Report, then you likely already know that the events of the last three years had nothing whatsoever to do with a virus. But if the pandemic was actually a scamdemic and it was never really about a viral contagion, then what was it about?

There are, of course, many answers to that question. The scamdemic served a number of agendas and the various players on the grand chessboard each had their own incentives for playing along with it. But one of the most important—not to mention one of the most overlooked—answers is that the scamdemic was, at base, a financial coup d’état. And that entire coup d’état was engineered by (you guessed it) BlackRock.

Last week, I presented A Brief History of BlackRock.

Next week, we will examine the Aladdin system, the ESG scam and where BlackRock is hoping to take society in the future.

This week, we will interrogate the scamdemic narrative, learn about the Going Direct Reset at its heart, and discover how BlackRock pulled off this financial coup d’état.

Want to know the details? Of course you do. Let’s dive in.

*NOTE: This is Part 2 of the How BlackRock Conquered the World Series.

Part 1: A Brief History of BlackRock was released last week.

Part 3 on BlackRock’s plans for the future will be released next week.

PART 2: GOING DIRECT

Last week, we ended our little history lesson in 2019, an extremely important year for the BlackRock takeover of the planet.

In January of that year, Joe Biden crawled cap-in-hand to Larry Fink’s Wall Street office to seek the financial titan’s blessing for his presidential (s)election. (“I’m here to help,” Fink reportedly replied.)

Then, on August 22nd of that year, Larry Fink joined such illustrious figures as Al “Climate Conman” Gore, Chrystia “Account Freezing” Freeland, Mark “GFANZ” Carney, and the man himself, Klaus “Bond Villain” Schwab, on the World Economic Forum’s Board of Trustees, an organization which, the WEF informs us, “serves as the guardian of the World Economic Forum’s mission and values.” (“But which values are those, precisely?” you might ask, “And what does Yo-Yo Ma have to do with it?”)

It was another event that took place on August 22nd, 2019, however, that captures our attention today. As it turns out, August 22nd was not only the date that Fink achieved his globalist knighthood on the WEF board, it was also the date that the financial coup d’état (later erroneously referred to as a “pandemic”) actually began.

In order to understand what happened that day, however, we need to take a moment to understand the structure of the US monetary system. You see (GREATLYoversimplifying things for ease of understanding), there are actually two types of money in the banking system: there is “bank money”—the money that you and I use to transact in the real economy—and there is “reserve money”—the money that banks keep on deposit at the Federal Reserve. These two types of money circulate in two separate monetary circuits, sometimes referred to as the retail circuit (bank money) and the wholesale circuit (reserve money).

In order to get a handle on what this actually means, I highly suggest you check out John Titus’ indispensable videos on the subject, notably “Mommy, Where Does Money Come From?“, “Wherefore Art Thou Reserves?” and “Larry and Carstens’ Excellent Pandemic.”

But the point of the two circuit system is that, historically speaking, the Federal Reserve was never able to “print money” in the sense that people usually understand that term. They are able to create reserve money, which banks can keep on deposit with the Fed to meet their capital requirements. The more reserves they have parked at the Fed, the more bank money they are allowed to conjure into existence and lend out into the real economy. The gap between Fed-created reserve money and bank-created bank money acts as a type of circuit breaker, and this is why the flood of reserve money that the Fed created in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008 did notresult in a spike in commercial bank deposits.

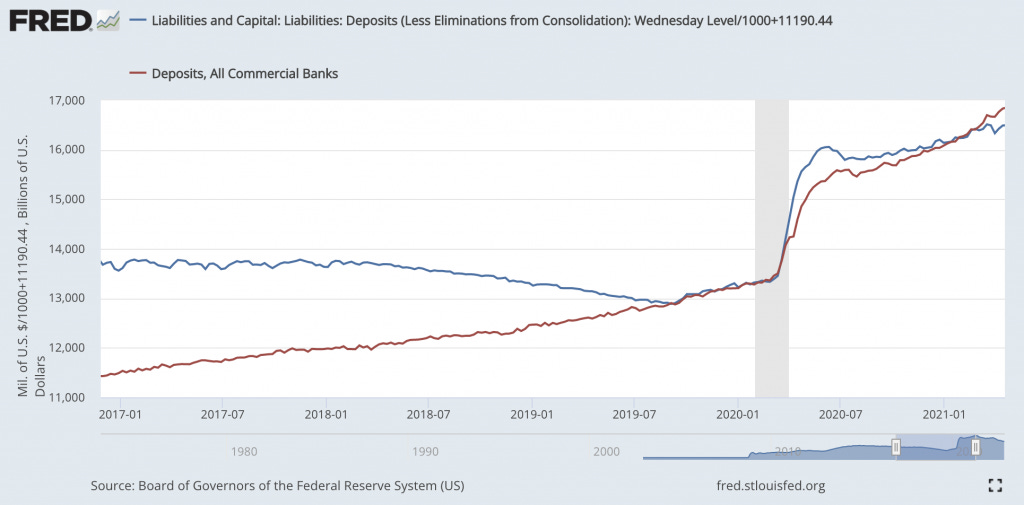

But all that changed three years ago. As Titus observes, by the time of the scamdemic bailouts of 2020, the amount of bank money sitting in deposit in commercial banks in the US—a figure which had never shown any correlation with the total amount of reserves held on deposit at the Fed—suddenly spiked in lock step with the Fed’s balance sheet.

Something happened between the 2008 bailout and the 2020 bailout. Whereas the tidal wave of reserve money unleashed to capitalize the banks in the earlier bailout hadn’t found its way into the “real” economy, the 2020 bailout money had.

So, what happened? BlackRock happened, that’s what.

Specifically, on August 15, 2019, BlackRock published a report under the typically eye-wateringly boring title, “Dealing with the next downturn: From unconventional monetary policy to unprecedented policy coordination.” Although the paper did not catch the attention of the general public, it did generate some press in the financial media, and, much more to the point, generated interest from the gaggle of central bankers that descended on Jackson Hole, Wyoming, for the annual Jackson Hole Economic Symposium taking place on August 22, 2019—the exact same day that Fink was being appointed to the WEF’s board.

The theme of the 2019 symposium—which brings together central bankers, policymakers, economists and academics to discuss economic issues and policy options—was “Challenges for Monetary Policy,” and BlackRock’s paper, published a week in advance of the event, was carefully crafted to set the parameters of that discussion.

It’s no surprise that the report would have caught the attention of the central bankers. After all, BlackRock’s proposal came with a pedigree. Of the four co-authors of the report, three of them were former central bankers themselves: Philipp Hildebrand, the former president of the Swiss National Bank; Stanley Fischer, the former Federal Reserve vice chairman and former governor of the Bank of Israel; and Jean Boivin, the former deputy governor of the Bank of Canada.

But beyond the paper’s authorship, it was what “Dealing with the next downturn” actually proposed that was to have such earth-shaking effects on the global monetary order.

The report starts by noting the dilemma that the central banksters found themselves in by 2019. After years of quantitative easing (QE) and ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) and even the once-unthinkable NIRP (negative interest rate policy), the banksters were running out of room to operate. As BlackRock notes:

The current policy space for global central banks is limited and will not be enough to respond to a significant, let alone a dramatic, downturn. Conventional and unconventional monetary policy works primarily through the stimulative impact of lower short-term and long-term interest rates. This channel is almost tapped out: One-third of the developed market government bond and investment grade universe now has negative yields, and global bond yields are closing in on their potential floor. Further support cannot rely on interest rates falling.

The would-be central planners’ only other option for getting money into the economy (fiscal spending overseen by legislature) was similarly doomed to fail in the event of an economic crash:

Fiscal policy can stimulate activity without relying on interest rates going lower – and globally there is a strong case for spending on infrastructure, education and renewable energy with the objective of elevating potential growth. The current low-rate environment also creates greater fiscal space. But fiscal policy is typically not nimble enough, and there are limits to what it can achieve on its own. With global debt at record levels, major fiscal stimulus could raise interest rates or stoke expectations of future fiscal consolidation, undercutting and perhaps even eliminating its stimulative boost.

So, what was BlackRock’s answer to this conundrum? Why, a great reset, of course!

No, not Klaus Schwab’s Great Reset. A different type of “great reset.” The “Going Direct” reset.

An unprecedented response is needed when monetary policy is exhausted and fiscal policy alone is not enough. That response will likely involve “going direct”: Going direct means the central bank finding ways to get central bank money directly in the hands of public and private sector spenders. Going direct, which can be organised in a variety of different ways, works by: 1) bypassing the interest rate channel when this traditional central bank toolkit is exhausted, and; 2) enforcing policy coordination so that the fiscal expansion does not lead to an offsetting increase in interest rates.

The authors of BlackRock’s proposal go on to stress that they are not talking about simply dumping money into people’s account willy-nilly. As report co-author Phillip Hildebrand made sure to stress in his appearance on Bloomberg on the day of the paper’s release, this was not Bernanke’s “helicopter money” idea. Nor was it—as report co-author Jean Boivin was keen to stress in his January 2020 appearance on BlackRock’s own podcast discussing the idea—a version of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), with the government simply printing bank money up to spend directly into the economy.

No, this was to be a process where special purpose facilities—which they called “standing emergency fiscal facilities” (SEFFs)—would be created to inject bank money directly into the commercial accounts of various public or private sector entities. These SEFFs would be overseen by the central bankers themselves, thus crossing the streams of the two monetary circuits in a way that had never been done before.

Any additional measures to stimulate economic growth will have to go beyond the interest rate channel and “go direct” – when a central bank crediting private or public sector accounts directly with money. One way or another, this will mean subsidising spending – and such a measure would be fiscal rather than monetary by design. This can be done directly through fiscal policy or by expanding the monetary policy toolkit with an instrument that will be fiscal in nature, such as credit easing by way of buying equities. This implies that an effective stimulus would require coordination between monetary and fiscal policy – be it implicitly or explicitly. [Emphases added.]

Alright, let’s recap. On August 15, 2019, BlackRock came out with a proposal calling for central banks to adopt a completely unprecedented procedure for injecting money directly into the economy in the event of the next downturn. Then, on August 22, 2019, the central bankers of the world convened in Wyoming for their annual shindig to discuss these very ideas.

So? Did the central bankers listen to BlackRock? You bet they did!

Remember when we saw how commercial bank deposits began moving in sync with the Fed’s balance sheet for the first time ever? Well, let’s take another look at that, shall we?

It wasn’t the March 2020 bailouts where the correlation between the Fed balance sheet and commercial bank deposits—the tell-tale sign of a BlackRock-style “going direct” bailout—began. It was actually in September 2019—months before the scamdemic was a gleam in Bill Gates’ eye—when we started to see Federal Reserve monetary creation finding its way directly into the retail monetary circuit.

In other words, it was less than one month after BlackRock proposed this revolutionary new type of fiscal intervention that the central banks began implementing that very idea. The Going Direct Reset—better understood as a financial coup d’état9—had begun.

To be sure, this going direct intervention was later offset by the Fed’s next scam for forcing more government debt on depositors, but that’s another story. The point is that the seal had been broken on the going direct bottle, and it wasn’t long before the central bankers had a perfect excuse for forcing that entire bottle down the public’s throat. What we were told was a “pandemic” was in fact, on the financial level, just an excuse for an absolutely unprecedented pumping of trillions of dollars from the Fed directly into the economy.

The story of precisely how the going direct reset was implemented during the 2020 bailouts is a fascinating one and I would encourage you to dive down that rabbit holeif you’re interested. But for today’s purposes, it’s sufficient to understand what the central bankers got out of the Going Direct Reset: the ability to take over fiscal policy and to begin engineering the economy of main street in a more . . . well, direct way.

But what did BlackRock get out of this, you ask? Well, when it came time to decide who to call in to manage the scamdemic bailout scam, guess who the Fed turned to? If you guessed BlackRock, then (sadly) you’re exactly right!

Yes, in March 2020 the Federal Reserve hired BlackRock to manage three separate bailout programs: its commercial mortgage-backed securities program, its purchases of newly issued corporate bonds and its purchases of existing investment-grade bonds and credit ETFs.

To be sure, this bailout bonanza wasn’t just another excuse for BlackRock to gain access to the government purse and distribute funds to businesses in its own portfolio, though it certainly was that.

And it wasn’t just another emergency where the chairman of the Federal Reserve had to put Larry Fink on speed dial—not just to shower BlackRock with no-bid contracts but to manage his own portfolio—although it certainly was that, too.

It was also a convenient excuse for BlackRock to bail out one of its own most valuable assets: iShares, the collection of exchange traded funds (ETFs) that it acquired from Barclays for $13.5 billion in 2009 and which had ballooned to a $1.9 trillion juggernaut by 2020.

As Pam and Russ Martens—who have been on the BlackRock beat at their Wall Street On Parade blog for years now—detailed in their article on the subject, “BlackRock Is Bailing Out Its ETFs with Fed Money and Taxpayers Eating Losses“:

BlackRock is being allowed by the Fed to buy its own corporate bond ETFs as part of the Fed program to prop up the corporate bond market. According to a report in Institutional Investor on Monday, BlackRock, on behalf of the Fed, “bought $1.58 billion in investment-grade and high-yield ETFs from May 12 to May 19, with BlackRock’s iShares funds representing 48 percent of the $1.307 billion market value at the end of that period, ETFGI said in a May 30 report.”

No bid contracts and buying up your own products, what could possibly be wrong with that? To make matters even more egregious, the stimulus bill known as the CARES Act set aside $454 billion of taxpayers’ money to eat the losses in the bail out programs set up by the Fed. A total of $75 billion has been allocated to eat losses in the corporate bond-buying programs being managed by BlackRock. Since BlackRock is allowed to buy up its own ETFs, this means that taxpayers will be eating losses that might otherwise accrue to billionaire Larry Fink’s company and investors.

At the time that the Fed’s contract with BlackRock to manage the ETF purchase program was announced, the mockingbird repeaters at The New York Times attempted to run cover for the swindle by pointing out that the contract that the Fed signed would ensure that BlackRock “will earn no more than $7.75 million per year for the main bond portfolio it will manage” and that the firm “will also be prohibited from earning fees on the sale of bond-backed exchange traded funds, a segment of the market it dominates.”

But this, of course, completely (and no doubt deliberately) misses the point.

As The Wall Street Journal reported in September 2020, BlackRock’s revenue rose 11.5% to $261 million in the second quarter of 2020 on the back of a $34 billion surge in ETFs under BlackRock management. As Bharat Ramamurti, a member of the congressional body overseeing the Fed’s coronavirus stimulus programs, noted in the report, the fundamental scam that BlackRock pulled is not exactly rocket science.

Even if BlackRock waives its fees from the purchases that the Fed is making, the fact that it is associated with this program means that other investors are going to rush into BlackRock funds. BlackRock obviously generates fees from those flows. So the net result is that this is very lucrative for BlackRock.

The numbers speak for themselves. After BlackRock was allowed to bailout its own ETF funds with the Fed’s newly minted going direct funny money, iShares surged yet again, surpassing $3 trillion in assets under management last year.

But it wasn’t just the Fed that was rolling out the red carpet for BlackRock to implement the very bailout plan that they created. Banksters from around the world were positively falling over themselves to get BlackRock to manage their market interventions.

In April 2020, the Bank of Canada announced that it was hiring (who else?) BlackRock’s Financial Markets Advisory (FMA) to help manage its own $10 billion corporate bond buying program. Then in May 2020, the Swedish central bank, the Riksbank, also hired BlackRock as an external consultant to conduct “an analysis of the Swedish corporate bonds market and an assessment of possible design options for a potential corporate bonds asset purchase programme.”

As we saw in Part 1 of this exploration, the Global Financial Crisis had put BlackRock on the map, establishing the firm’s dominance on the world stage and catapulting Larry Fink to the status of Wall Street royalty. With the 2020 Going Direct Reset, however, BlackRock had truly conquered the planet. It was now dictating central bank interventions and then acting in every conceivable role and in direct violation of conflict of interest rules, acting as consultant and advisor, as manager, as buyer, as seller and as investor with both the Fed and the very banks, corporations, pension funds and other entities it was bailing out.

Yes, with the advent of the scamdemic, BlackRock had cemented its position as The Company That Owns The World.

But yet again we are left with the same nagging question: What is BlackRock seeking to do with this power? What is it capable of doing? And what are the aims of Fink and his fellow travelers?

The answer, which we will discuss next week, is that BlackRock is now seeking to bend society itself to its will, shaping the course of civilization in the process.

Stay tuned for Part 3 of this series where we will gaze into the crystal ball to see The Future According to BlackRock. . . .

c/o The Corbett Report