Political Ponerology

![]()

Logocracy – Chapter 11: Logocratic Law

Reforming civil, criminal, and family law

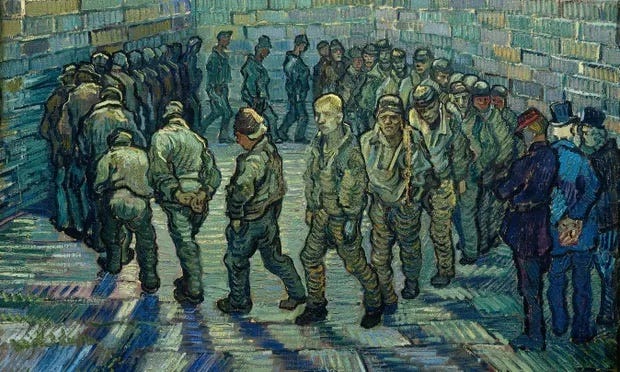

For Lobaczewski, WWII showed how the modern formulation of European law could be bent toward inhuman purposes, providing cover for the worst sorts of crimes imaginable. Not only that—Western democracies in the post-war period proved that such legal systems left them at risk, helpless in the face of phenomena they did not understand. As he first argued more broadly in Political Ponerology, this is because such legal philosophies and traditions do not take into account the nature and genesis of evil, and specifically “the contribution of pathological factors,” i.e. inherited and acquired personality pathologies.

A general trend in law over the past couple centuries has been a degree of “psychologization”—the introduction of certain psychological insights into the understanding of man and its implications for the practice of law. A basic example: the M’Naghten rules, or insanity defense, which mitigates legal culpability in the face of various biopsychological conditions (including certain physical diseases). Psychologists are regularly used as expert witnesses at trial, for instance, and their assessments contribute to criminal sentencing. The field has expanded in recent years and is the subject of much academic work. See, for example, The Wiley International Handbook on Psychopathic Disorders and the Law (1,984 pages!).

For Lobaczewski, this process is in its infancy, somewhat chaotic and still exploratory in nature—both in the progress of the science of psychology and in its legal applications. He suggests that the development of ponerology as a discipline “should help to concretize the goals of this process and speed it up,” though it would take at least a generation of work. Supporting this process is consistent with the logocratic conception of natural law—law consistent with human nature, biological and spiritual. However, reiterating logocracy’s evolutionary principle, traditional legal practices must be preserved and act as the foundation.

Lobaczewski writes positively of English common law, but not the American variety. He thinks legal studies should move towards a more scientific method, “where the basis is the epistemological and methodological inquiry into causes, and the objective cognition of reality. … The logocratic system will need fewer, but better prepared, lawyers.”

Types of law should be nested hierarchically; for example, natural law will trump positive law when the two come into conflict, the ideal being expressed as follows:

The law cannot act ponerogenically. The law will lose the severity of its letter, and the possibility of a deliberate exploitation of its loopholes and defects to extract unlawful benefits will cease.

On criminal law, he notes the move away from traditional forms of punishment towards a more humanizing, rehabilitative law. While he welcomes this move, he points out that it hasn’t been without its own negative consequences:

Currently, this breeds a lack of fear of the severity of the law, which is exploited by common criminals and organized political terrorists. The world has faced an incredible increase in all forms of crime.

He believes it possible, and advisable, to solve this problem without reverting to old forms. What is needed is for the law to incorporate a ponerological understanding of the origin of evil, the methods derived from which “should protect man and public order at least as effectively.” This will entail an approach more geared toward individual psychological realities, less so to one-size-fits-all generalizations. “The primary concern must be preventive action.”

On the notion of guilt:

…the more we know about the psychological life of man and his internal and external causality, the more our awareness of our ignorance grows in the area of the possibility of objectively knowing the share of [another’s] guilt.

Gaining an understanding into the causal pathways of evil, and staying objective while doing so (maintaining one’s mental hygiene), means refraining from moralistic judgment—a process familiar to psychologists and also recommended for judges. Judgment is best reserved for one’s own behavior, guided by one’s conscience.

Traditional criminal law is in fact in conflict with these requirements and is therefore ineffective and often breeds new evils.

That’s not to say justice should be neglected, or toothless. Its focus should be concerned with the facts of the crime, and the chain of moral complicity. Such public disclosure, Lobaczewski argues, will itself act as a kind of punishment for those who contribute to ponerogenesis, whether “by bad human upbringing, persuasion, negligence, or selfishness.” Since pathological factors are virtually always present in common crime (whether acting “from within” or from the influence of others), this will be a guiding assumption necessitating psychological evaluations—another disincentivizing measure.

Corrective measures will be catered toward the specific mental characteristics, type of pathology, personal history, and talent level of the perpetrator. These will involve restrictions on the offender’s liberty, but sentencing will not be based on measures of time, rather by specific tasks and their completion.

If the convict accepts such a sentence and works sincerely for its implementation, he will be able to significantly reduce the time of his rehabilitation. Typical tasks will include doing some socially useful work, completing the appropriate schooling and learning a trade, preparing a written elaboration discussing his act, its causes, social harm, and the role of others, etc. In many cases, the convicted person will be obliged to undergo psychotherapy, and a method will be applied to psychopathic individuals to make them aware of their aberrations and make them abandon their struggle with the society of normal people.

However, since psychopaths are incapable of normal work (and most lack any technical aptitude) and of changing their inner nature, this should be taken into account. “As long as societies do not decide to provide them with the necessary understanding and conditions for a legitimate existence,” they risk descent into pathocracy. The current prison system in which such individuals get caught up is “an unproductive waste of time and money,” and in fact only transforms prisons into “schools of crime.” Converting to a preventive system incorporating “legal and psychological supervision” of psychopathic criminals (who currently make up around 16% of the U.S. prison population) will be no more expensive than the current prison system, but will produce better results.

As an example of preventive causal measures, Lobaczewski brings up compulsory education, calling such a practice “perfidious” and degrading to individuals unable to comprehend the curricula, inspiring feelings of inadequacy and hostility to others. It’s a source of suffering and suicide—unenforceable and criminogenic in nature. “Compulsory schooling was appropriate because many parents did not understand the need for it, at a time when illiteracy and a lack of necessary education impeded social development. Today it is a relic.”

He reiterates another principle first included in Political Ponerology: that those most likely to make legal accusations against another’s mental health are those who are themselves abnormal. On the political level, nations who subject political dissidents to forced psychiatric “treatment” should also be assumed to be operating on a psychopathological basis.

Regarding capital punishment, a guiding assumption of criminal justice should be “that any normal person can be rehabilitated.” Only when this proves impossible with certain individuals should it be inferred that the individual is fundamentally abnormal—something to be confirmed by research. Underneath the element of moralistic punishment, capital punishment has always been “a way of eliminating pathological asocial individuals.” However, this purpose is easily perverted, as in the case of political dissidents and patriots. Its practice should thus be “a rare necessity and not done under the guise of punishment.”

But to keep alive individuals who continue to threaten others with death or disability would be to deprive the latter of legal protection. The killing of such individuals will therefore become a necessity to which the state has the right. This would then be decided by a special state institution and not by a court.

Lobaczewski deems military coercion under penalty of death, and forced conscription, to be contrary to natural law.

Finally, he observes that “In the existing legislation there are no provisions that would protect the mental health of an individual who is threatened by the terrorizing influence of pathological individuals. Special protection in this regard should be given to those people on whom the fate of other citizens depends.” This issue is only now being recognized by psychologists, as seen in the explosion of research in the Dark Tetrad personality traits. Implementing these insights will take some time.

Chapter 11: Logocratic Law

European laws, formed under the influence of Roman law, acquired their modern form in the 19th century, undergoing only limited modifications thereafter. To the generation of our fathers and grandfathers, such law may have seemed complete in its philosophy and logic, something simply to be learned and embellished with the art of oratory in order to pursue a legal career. The times of the last war showed us how such law could be bent, how to use the shirt of legal formula to clothe the worst crimes. The post-war times have shown how the legal formalism deeply rooted in Western democracies makes them inadequate in the face of new evils because it ignores their nature, genesis, and the contribution of pathological factors. At the same time, in light of contemporary developments in the sciences, especially in the biohumanities, many of the old formulations are beginning to raise questions of fact and humanistic criticism.

In all free countries, the law has already entered a period of accelerated evolution, uncertainty of criteria, and search for new solutions. The directions of this evolution are already outlined, and it has become obvious that a gradual psychologization of the law is taking place. However, this process has not yet reached a certain landmark peak from which we could see clearly its destination. We also encounter deficits in the progress of specific sciences that make it difficult to find new more adequate solutions. The development of ponerology, mentioned in Chapter 4, should help to concretize the goals of this process and speed it up.

All this should convince us that this fundamentally necessary process, which will transform the law into its more perfect form, cannot be accelerated by revolutionary means or accomplished outside the necessary parameter of time. On the basis of the ever-improving achievements of the social sciences, finding more perfect legal solutions will become a path that must take at least a generation. The logocracy, which has accepted the wisdom of eternal laws and modern scientific cognition as the basis of its organization, should be at the forefront of this process of legal reconstruction, finding solutions more easily based on an understanding of natural law. Nevertheless, it will have to accept such a situation where, in a modernized system and in the light of a new constitutional law, many traditional legal solutions will be preserved. In the eyes of a zealous logocrat, such a state of affairs may seem unsatisfactory, but he will understand that he will only be able to contribute to a more rapid evolution of the law through research or constructive legislative work.

In democratic capitalist countries, and even more so where a well-developed system of medical and psychological care is favored and some pressure is exerted by socialist parties, criminal law is evolving into a law of rehabilitation. Civil law undergoes only minor modifications there, sometimes harmful ones. In a logocratic system, both these branches of law will have to evolve and modernize. The cause of improvements in civil law would be the new philosophy of property ownership sketched in the previous chapter. The principles of public sovereignty and competence would entail changes in constitutional law as well as in many other areas. Psychological realism would entail an evolution of what has hitherto been called “criminal” law, as well as changes in family law and related areas.

In a law subordinated to the natural cognition of the laws of nature, from which the natural law derives, there appears the hierarchy of criteria already familiar to us, in which the objective cognition of the laws of nature, as given by the Creator, will constitute the most general source of law, accessible to scientifically armed minds. A provision, therefore, of positive law, even of the traditional kind, will have a regulatory power somewhat weaker and to a greater extent limited to matters which the legislators could understand and foresee. Nor will it be able to come into collision with the law of a higher class or be used to do harm. The law cannot act ponerogenically. The law will lose the severity of its letter, and the possibility of a deliberate exploitation of its loopholes and defects to extract unlawful benefits will cease. If this leads to the conviction that there is no adequate legal regulation of the matter in question, the decision should be made in the light of natural law and the sense of justice, and the state of affairs should be brought to the attention of the legislature.

Nor can such a law resemble America’s anachronistic “common law,” where the average attorney cannot afford to purchase the volumes of law and case law applicable in his or her state. It can, however, resemble English modernized law of this type.

Modern societies, horrified by the abuses of the law in the era of the last war and by totalitarian regimes, are moving towards humanizing the law and replacing criminal law with rehabilitative law. Currently, this breeds a lack of fear of the severity of the law, which is exploited by common criminals and organized political terrorists.

The world has faced an incredible increase in all forms of crime. Therefore, there is a need for new laws and methods of procedure which, using the progress of scientific knowledge, will meet the requirements of modern humanism, but will not be less effective than the old harsh laws. Starting from an understanding of the processes of the origin of evil, such methods should protect man and public order at least as effectively. It is obvious, therefore, that such methods will be more complex and will have different means of action adapted to individual psychological realities. The primary concern must be preventive action. Punishment, as the old panacea for combating evil, may seem a relic to future generations.

Advances in the knowledge of the psychological causality which operates in man enable us to understand ourselves and others better, to find good counsel in difficulties, and, if necessary, effective means of preventing evil and of corrective action. Advances in the understanding of various mental deviations, whether acquired or hereditary, make it possible to study their involvement in ponerogenic processes on every social scale. By studying the nature of evil, its causes and its processes of genesis, we can develop a more critical social consciousness, which should become a fundamental factor in inhibiting these processes, as well as new means of counteracting them.

Meanwhile, science has made almost no progress in the field of knowledge and evaluation of another person’s guilt. On the contrary, the more we know about the psychological life of man and his internal and external causality, the more our awareness of our ignorance grows in the area of the possibility of objectively knowing the share of his guilt. We can know more about ourselves because we are aided by our conscience, but even here this knowledge can be burdened with considerable errors. Judgments about another person’s guilt are justified by our instinctive reflexes and emotionalism, by acquired archetypes of understanding, by the practical necessities of social life, and by certain religious doctrines. The psychologist, however, in order to be able to concentrate his attention on cognizable causality and to maintain the hygiene of his own mind, renounces judging the faults of others as an activity which is beyond his human capacity. A similar right to maintain one’s own mental hygiene should also be exercised by judges, in order to avoid a professional warping of their personality.

Modern psychology seems to confirm in a rational way what is said in the Gospel of Christianity and what can be found in the books of the great religions of the East, where it is demanded that we refrain from judging others. We have the ability and the duty to judge our own behavior by using the voice of our conscience, but we do not have this ability with respect to another person. Traditional criminal law is in fact in conflict with these requirements and is therefore ineffective and often breeds new evils. Logocratic law cannot require a man in a robe to make judgments that are in conflict with respect for cognizable truth or that lie beyond the limits of human cognition.

The logocratic court should, as far as possible and to a greater extent than is the case in modern practice, state the facts of the crime, pointing out the moral complicity of those people who have contributed to its origin. The disclosure of this will always be an effective measure against evil and a kind of punishment for those who, by bad human upbringing, persuasion, negligence, or selfishness, have contributed to the evil. The court, on the other hand, will seek ways of correcting man, of course using the necessary coercion, which will have the effect of punishment. The basis for this will be relevant objective knowledge, not beliefs based on a common psychological worldview. This will open the way for the use of those scientific achievements which will make it possible to prevent ponerogenesis processes more effectively—because causally—or to eliminate their effects.

A man who has committed a criminal act will always be suspected of having acted in him some pathological factor of which he is the bearer, or of having been influenced by the pathological properties of others during his childhood or in connection with the act committed. In any case, therefore, he will be examined by the methods of clinical psychology and, if necessary, by psychiatry. For many people, this will be an extremely discouraging prospect for committing acts in conflict with the law.

Specialists will present to the court, composed of persons with appropriately modernized scientific preparation, the actual mental characteristics of the perpetrator of the deed, such as: his general level and quality of talents, the state of the brain with possible localized description of damage to its tissue and its consequences, deviations from the qualitative norm of probable hereditary nature. The psychologist will characterize the genesis of his personality defects, and the contribution of the detected pathological factors to the genesis of his act. On this basis, the court will receive indications as to appropriate corrective measures. The court will not judge the conduct of a man who does not understand, nor will it judge the image of him that has been formed in the minds of the judges. The court will consider psychologically feasible means of his rehabilitation and adaptation to life in the society of normal people.

The court will determine a course of corrective action, which will obviously involve a restriction of the offender’s liberty. The court will not use the basic measure of the time of punishment, but will impose an appropriate corrective task on the offender, obviously feasible within the scope of his real possibilities. If the convict accepts such a sentence and works sincerely for its implementation, he will be able to significantly reduce the time of his rehabilitation. Typical tasks will include doing some socially useful work, completing the appropriate schooling and learning a trade, preparing a written elaboration discussing his act, its causes, social harm, and the role of others, etc.

In many cases, the convicted person will be obliged to undergo psychotherapy, and a method will be applied to psychopathic individuals to make them aware of their aberrations and make them abandon their struggle with the society of normal people.

Logocratic societies and their laws must accept the fact, obvious to psychologists, that in every country there are individuals who are incapable of providing for themselves by means of normal work. These are the carriers of brain tissue damage, psychopathic individuals, and others. Psychopaths try to hide their handicap under the mask and role of normality, but in reality they are incapable of developing a common worldview and human attitudes, and in a large majority they show a deficit of craftsmanship and technical aptitude. When confronted with the demands of the job, they hide their deficiencies with excessive talkativeness, creating confusion and spoiling the work. Thus, they are sometimes removed and thus condemned to disloyal combat with society in their efforts to parasitize on its heritage.

Among such people, especially the psychopathic, there arises the dream of a social system in which they would exercise power and impose on the “different” normal people their own understanding of life, which would ensure their welfare and sense of security. As long as societies do not decide to provide them with the necessary understanding and conditions for a legitimate existence, the danger of realizing this dream, with the help of some new suitably distorted ideology, will continue to hang over the world.

Trying and punishing people who are essentially handicapped, and often treating them as repeat offenders, is an unproductive waste of time and money. In addition, such treatment contributes to the transformation of prisons into schools of crime and, in other ways, increases the incidence of crime.

Such people should already be accommodated prophylactically under proper legal and psychological supervision, providing them with the opportunity to seek good counsel.

This will, of course, cost society money, but such treatment will be no more expensive than the present one, and will produce better results.

With regard to preventive activities based on a deeper understanding of causality, this can be illustrated by a very current example in Poland. Article 70 paragraph 1 of the Constitution stipulates: “Everyone has the right to education. Education up to the age of 18 shall be compulsory.” If someone wanted to invent a more perfidious way of degrading an individual who is too poorly gifted to comprehend the curriculum and of developing in him a complex of inadequacy, a conviction of the stupidity of normal people, as well as hostility towards those who are gifted, than the compulsion to sit at a school desk, he would be in no small trouble. Therefore, if we try to carry out the provision of the said paragraph of the constitution, we must be prepared for more and more high school graduates to pay for it with suffering and even with their lives.

Therefore, this provision of the constitution should be considered both unenforceable in practice and also—criminogenic. As such, it should be declared null and void.

Compulsory schooling was appropriate because many parents did not understand the need for it, at a time when illiteracy and a lack of necessary education impeded social development. Today it is a relic. In a logocratic system, a suitably adjusted family law should provide a more natural solution to these matters, taking into account the talents of individuals and other psychologically understandable aspects.

The differences between the present law, based on the “common sense” of the common psychological worldview, and the logocratic law based on scientific cognition, can be illustrated by an example from a field well known to the author. If “A” accuses “B” of being mentally abnormal, then, according to the existing understanding of such events, B is suspected of abnormality, and he himself and his reputation in society will suffer severely. B, in turn, may seek a legal defense by proving his normality. He may even get A convicted, but in practice this is exceedingly rare.

Psychiatric experience and psychological analysis of such cases teach, however, that the idea of accusing someone of mental abnormality arises most often in abnormal minds, and much less often in people who have only a bad conscience toward the accused. Therefore, for the specialist, both A and B are suspected of being mentally abnormal. Thus, according to logocratic law, if A accuses too intrusively, he should be subjected to a psychological examination. Such a law would allow the situation to be adequately explained. At the same time, it would prove to be much more effective in discouraging people inclined to use these vile weapons.

Similarly, if in some country there appears a method of accusing political opponents or critics of the ruling power of mental abnormality and mental illness, and even subjecting them to forced psychiatric “treatment,” then, according to scientific understanding of such matters and logocratic law, such a regime would have to be considered a system with a psychopathological basis. This opens up one pathway to understanding the true nature of such supposedly “autocratic” systems.

In the existing legislation there are no provisions that would protect the mental health of an individual who is threatened by the terrorizing influence of pathological individuals. Meanwhile, such influence has a significant share in the processes of ponerogenesis. The logocratic law should develop such provisions and introduce them into theory and practice. Special protection in this regard should be given to those people on whom the fate of other citizens depends. For the logocracy will be a system of normal people and only to them will be entrusted responsible offices. Judges, who in the execution of the existing principles of law are easily subjected to occupational deformation of personality, should be protected by including this aspect in the entire reform of the law.

The concept of capital punishment does not fit into the assumptions of logocratic law. According to current theory, the death penalty is not applied to mentally abnormal individuals. In accordance with psychological realities, it should be assumed that any normal person can be rehabilitated. If this proves impossible, it should be inferred that he is abnormal, which will be confirmed by research. In practice, capital punishment is a way of eliminating pathological asocial individuals. This formula, however, can be too easily extended to political opponents or defenders of the homeland. But to keep alive individuals who continue to threaten others with death or disability would be to deprive the latter of legal protection. The killing of such individuals will therefore become a necessity to which the state has the right. This would then be decided by a special state institution and not by a court. Then the killing would take place in the least painful way for the deceased. It would be a rare necessity and not done under the guise of punishment.

Military and war laws should be revised on similar lines. The use of coercion under penalty of death is contrary to natural law. Forced conscription of citizens who do not wish it or consider war unjust should therefore be prohibited by international law. This would weaken the power of aggressive countries more than those forced to defend themselves.

Such a fundamental reform of the law should begin with a similarly far-reaching reform of legal studies. These studies should lose their traditionally hallowed distinctiveness of character, based on philosophical doctrine. They should become similar to other fields, where the basis is the epistemological and methodological inquiry into causes, and the objective cognition of reality. Therefore, the future lawyer should obtain the necessary philosophical preparation to free his mind from the tendency to repeat errors long known to logicians and to make him capable of concise and truth-seeking thinking. The lawyer should be prepared to understand man and to cooperate with psychologists and physicians. The studies so reformed should produce lawyers with a research attitude capable of legislating and implementing new laws. The older cadres should be given the opportunity to study the necessary fields. The logocratic system will need fewer, but better prepared, lawyers. For less complex and administrative matters, a lower cadre of lawyers should be educated after an appropriate semi-secondary school, as is the practice in some countries.

Modern advances in the exact sciences, especially those that teach an understanding of man and society, open up hitherto unknown possibilities for new and better solutions to perennial and exceedingly complex individual and social problems. This should break the traditional conservatism of legal thinking, but exploiting these gifts of science will require a great deal of research and legislative work, and therefore time.

Note: This work is a project of QFG/Red Pill Press and is planned to be published in book form.

HK: In his 2017 review of the literature on criminal incapacitation (i.e. imprisonment), David Rodman concludes that “longer sentences do not clearly deter crime.” “Swift and certain punishment,” by contrast, “can deter, when practical [i.e. ‘where violation can be quickly and easily detected and sanctions can be delivered promptly’], but perhaps works mainly when complemented with positive incentives and appropriate treatment.” As for the deterrent effect of other factors (e.g. capital punishment, police, risk perceptions), see Apel and Nagin (2011). As Nagin writes in another piece: “The evidence in support of the deterrent effect of the certainty of punishment [more specifically, certainty of getting caught] is far more consistent than that for the severity of punishment.”

HK: In a blog piece summarizing the findings of his 2017 review, Rodman writes: “Run right, prisons can rehabilitate, by preparing people to enter the legal job market. Witness Norway.”

HK: In Rodman’s blog piece noted above, he writes: “After tough review, the bulk of the evidence says that in the United States today, prison is making people more criminal. The short-term crime reduction from incarcerating more people gets cancelled out in the long run.” In his full review, he concludes: “while imprisoning people temporarily stops them from committing crime outside prison walls, it also tends to increase their criminality after release. As a result, ‘tough-on-crime’ initiatives can reduce crime in the short run but cause offsetting harm in the long run.” Citing Nagin, Cullen, and Jonson (2009), he writes: “the prison experience may also be criminogenic. It may alienate people from society, giving them less psychological stake in its rules. It may make people better criminals by giving them months together to learn from each other. It may strengthen their allegiances to gangs whose social reach extends into prisons.”

HK: Another of Rodman’s conclusions from his review: “Intensively supervised release, possibly including electronic monitoring, can increase freedom and save money without increasing crime; but the political will needed to sustain and scale it has been scarce.”

HK: Poor school performance is strongly correlated with suicide attempts. As this abstract put it: “Academic performance in youth, measured by grade point average (GPA), predicts suicide attempt, but the mechanisms are not known. It has been suggested that general intelligence might underlie the association.” Or as this paper concludes: “Poor school performance was found to predict suicide attempts among young adults without a history of suicidal thoughts.”

HK: Apel and Nagin find conflicting evidence of any deterrent effect from the threat of capital punishment.

Subscribe to Political Ponerology

Pathopolitics, psychopathy, and mass hysteria