Species Unity and Dreaming

We are endowed with two naturally recurring states of consciousness, waking and dreaming. While distinct in form and content, they are complementary in working to maintain the integrity of the organism while at the same time maintaining the unity of the species. Waking consciousness is geared to the waking reality we face every day. Language is our tool for categorizing that reality and for communicating to others and to ourselves about it. Asleep and dreaming we register at a feeling level the impact of our social patterns of behavior on what Burrow refers to as our basic organismic needs. The language we resort to is an imagistic one metaphorically displaying the residual feelings we take to bed with us. Tensions arising during the day are explored in their connection to unfinished business from our past. Awake we are actors on the social scene. Asleep and dreaming we engage in an evaluative process signalling how well we are doing with regard to the level of honesty and authenticity we bring to our dealings with others. In Burrow’s terms our I-persona (our social facade) manifests itself in varying degrees of co-tensive (connecting with another) and di-tensive responses (failing to connect because of self-deceptive protective maneuvers) responses. The problem is that language is a two-edged tool equally available for revealing or concealing the truth.

Although Burrows did not seem to have a special interest in dreams, his insights into what he refers to as our phylobiological unity as a species and the fragmentation and separateness that has evolved as a consequence of our failure to recognize in practice the reality of this interconnectedness, is precisely what is addressed while dreaming. In fact, it is the dynamic underpinning of dreaming consciousness.

Let us look at this more closely. Dreaming is associated with a phylogenetically primitive subcortical arousal system that sees to it that repetitive bouts of arousal occur during sleep. The consciousness that accompanies these periods of arousal presumably serves an adaptive purpose. Both Evans (1983) and Winson (1986) have suggested that this provides the organism with the opportunity to modify their behavioral repertoire to meet new contingencies. Animals at a sub-human level are faced with the task of surviving in the wild. At the human level we are dealing with behavior patterns that have evolved in relation to survival in the socio-cultural environment in which we find ourselves. In both instances we are dealing with a genetically driven mechanism concerned with the survival of the species. What this ultimately comes down to with regard to the human species is how urgent it is, in view of our technological capacity for destruction, for behavioral patterns that unite us to prevail more decisively over behavior that separates us than has been the case up to now.

Our dreams are an ally in this task. They are not bound by the same rules that constrain waking behavior. They go beyond our I-persona that so often protects us from the full realization of the consequences of our behavior. Our dreams are truth seekers. They go by the same rules that apply to animals in the wild: the more truthful one’s perception of reality, the greater are the chances of survival of the individual and the species. Our dreams are associated with those arousal periods and speak to us in a primitive imagistic mode. In contrast to subhuman mammals, who presumably resort in a more concrete literal way to this imagistic mode, we humans call upon our imagination and our capacity for abstraction to put together imagery that speaks to us in a so creatively crafted metaphorically expressive imagery about both the good and the bad going on within us at the time. Our dreams have a no holds barred policy with regard to revealing the state of our connection to our own past and how connected we really are to others. We are creatures driven to survive as a species by moving to an ever expanding state of authentic interconnectedness.

Elsewhere I (Ullman (1981)) wrote:

(Our dreams are) organized by a different principle. Our dreams are more concerned with the nature of our connections with all others . . . . The history of the human race, while awake, is a history of fragmentation, of separating people and communities of people . . . nationally, religiously, politically, our dreams are connected with the basic truth that we are all members of a single species. (p. 1)

Responding to this, Richard Jones (1988) captured my meaning precisely and a bit poetically, when he wrote:

There’s the truth: In dreams our sentence in the individual life is suspended, as our perceptions of living are reconnected with those of our species, by way of a transcendent mental function which has united the human race over all human space and over all human time. No wonder that even some “bad°” dreams leave us feeling more whole, more human.

I may now refine my thesis: In dreams, where ego was shall species-feeling be. Our dreams are authored from within our individual lives merely to the extent that our self-interests provide their materials, their stuff, exactly the extent to which Shakespeare’s plays were authored by the stuff of old histories and legends. Indeed, it was Shakespeare from whom I learned what I am trying to say here: “We are such stuff as dreams are made on, And our little lives are rounded with a sleep.” (“Rounded,” in Elizabethan time, meant rounded out, not rounded in.) (p. 145)

We find ourselves in an imperfect world where the striving for power often derails the expression of love. Add to that the vicissitudes of language, and it is not surprising that each of us, without exception, grows up with a flawed I-persona. Dreams have little value in our culture. They are very low on the priority list so that most of us are ignorant of their significance with regard to the unity of the species and their potential for the self-healing of the individual. The past two decades have witnessed some changes in society’s attitude toward dreams with more and more books and periodicals appearing addressing the much needed task of educating the public. Perhaps once again Burrow’s emphasis on species unity will one day register more deeply through work on our dreams.

References:

Evans, Christopher (1983), Landscapes of the Night, New York, The Viking Press.

Jones, Richard (1988), Dream Reflection and Creative Writing, in M. Ullman and C. Limmer (eds.), The Variety of Dream Experience, New York, Continuum (pp. 171-213).

Ullman, Montague (1981), Psi Communication through Dream Sharing, in Parapsychology Review 12, No. 2.

Winson, Jonathan (1986), Brain and Psyche, New York, Vintage Books.

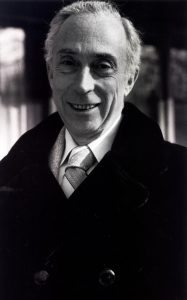

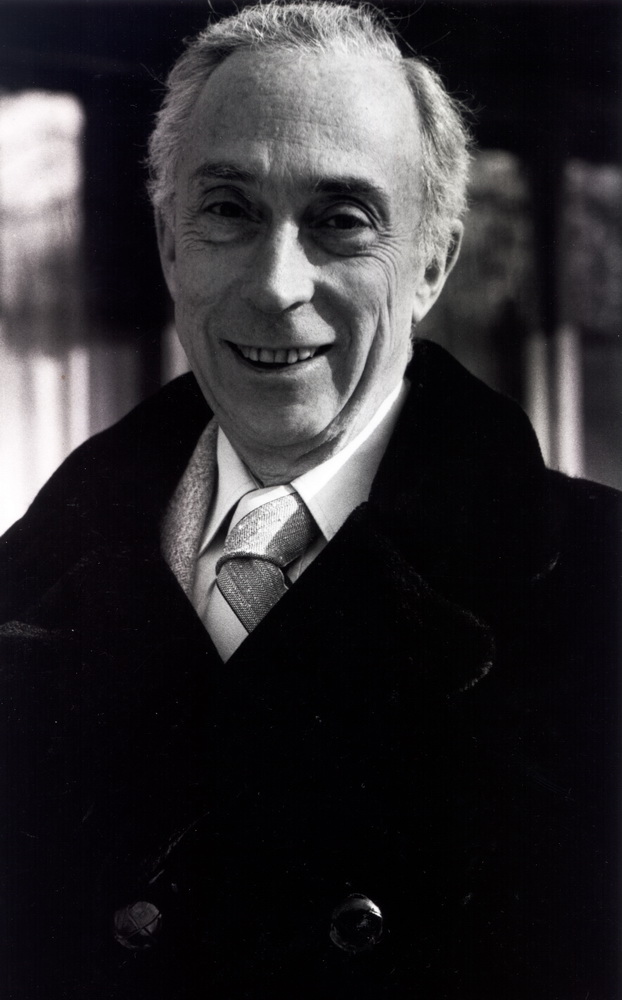

Montague Ullman

1916 – 2008

Dream Appreciation Newsletter Articles

This site is dedicated for the legacy of Montague Ullman’s dream work, consisting of Ullman’s own writings he wanted to be included in this site.

—-

All Images By Pixabay

—