The Outsider in the Twenty-First Century

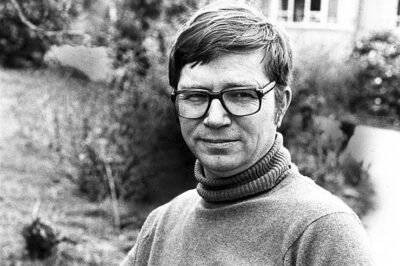

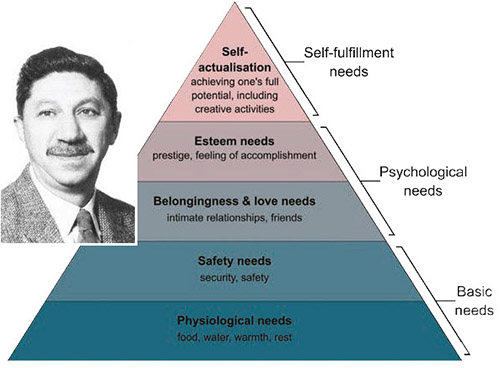

In his debut book, The Outsider, the twenty-four-year-old British existentialist Colin Wilson (1931–2013) made his first attempt at analysing a character he felt was peculiar to our age, or at least to that of the mid-twentieth century, when the book appeared.

In the midst of the buttoned-down, conforming 1950s, published in the same year as Allen Ginsberg’s Howl (1956)and a year before Kerouac’s On the Road (1957), Wilson’s “inquiry into the nature of the sickness of mankind in the mid-twentieth century” was the surprise bestseller of the season. Prestigious reviewers like Philip Toynbee, Cyril Connolly, J. B. Priestley, Edith Sitwell and others tripped over themselves, heaping praise upon the duffle-coated, polo-necked young Midlands genius, who had “walked into literature as a man walks into his own house.”

True, his investigation into the tortured lives of Nietzsche, Nijinsky, T.E. Lawrence (“of Arabia”), Van Gogh, and other creative individuals, straining against the banality of the modern world and their own psychological barriers, made for some heady holiday reading. But it was the summer of the Angry Young Men, and for a time, Wilson’s Outsider was in the news as much as Elvis Presley and James Dean, two rebels of a different sort.

As Wilson described him, his Outsider was someone with a pressing hunger for meaning and purpose in a world that was seemingly bent on denying him these.1 In the Middle Ages these individuals may have found a place in the church, which at that time still took such hunger seriously.

But in our modern – now post-modern – society, geared toward comfort, security, and conformity – what Wilson diagnosed in a later book as “other directedness” – there was no place for these individuals. They could find no home for their creative energies, and because of this, many of them came to a bad end. Nietzsche went insane, as did Nijinsky. Van Gogh killed himself. Lawrence committed a kind of “mental suicide,” retreating into anonymity as a private in the RAF, after the hollow celebrity following his Arab campaign. Many other Outsiders succumbed to drugs or alcohol or depression; only the strongest among them were able to break through the “fallacy of insignificance” and reach the source of “power, meaning, and purpose” within them. As one of Wilson’s Outsiders, the poet William Blake, put it in his Proverbs of Hell: “When thought is closed in caves, then love will show its roots in deepest Hell.” As Wilson’s many studies of “criminal Outsiders” show, when creative energy is frustrated, it turns upon the world before turning upon itself.

Outsiders, Wilson wrote in Religion and the Rebel, his follow-up to The Outsider, “appear like pimples on a dying civilisation.” In his most savage attack on the “lack of spiritual tension in a materially prosperous civilisation,” Wilson said that “the heroic figure of our time” was “the man who, for any reason at all, felt himself lonely in the crowd of the second-rate.” Ours was a time of “cheapness and futility, the degrading of all intellectual standards.” In response, the Outsider could be “a maniac carrying a knife in a black bag, taking pride in appearing harmless and normal to other people,” as the sex-murderer Austin Nunne in Wilson’s first novel, Ritual in the Dark, does. Or he “could be a saint or visionary, caring for nothing but one moment in which he seemed to understand the world, and see into the heart of nature and of God.”

The Wilson of The Outsider and Religion and the Rebel was convinced that western civilisation was in decline, and indeed, one of the thinkers whose work he looks at in Religion and the Rebel is Oswald Spengler, author of the monumental The Decline of the West. Yet even here, Wilson’s pessimism is more emotional than intellectual and may have been fuelled by the critical volte-face he received when the initial celebrity of The Outsider faded, and the intelligentsia decided that they were wrong about the “messiah of the milk bars.”

By the time he had finished writing Religion and the Rebel, whatever anger Wilson had felt, had been expressed. He later came to feel that his “world-rejection” and attack on a “sick civilisation” was a bit much, although he understood them to be necessary steps in the Outsider’s attempts to know himself, to become, in Nietzsche’s phrase, “who he is.” The later books in Wilson’s “Outsider Cycle” offer a patient, detailed, wide-ranging analysis of contemporary culture, philosophy, science, and psychology from the point of view of the Outsider’s peculiar challenge: to find a means of triggering the “visionary faculty,” the moments of “yea-saying” and “affirmation” that free him from his paralysis, and show him his true place, as one of civilisation’s creators, not its misfits.

Wilson died in 2013, at the age of eighty-two. In the years following his debut, he produced an enormous number of books on a wide range of subjects and an equal number of essays, articles, reviews, lectures, and introductions to the work of others, myself included. He remained upbeat and positive, even during the difficult years following a stroke that left him practically paralysed and unable to read or speak. He is one of the most optimistic voices in the literature and thought of the past two centuries, although his optimism isn’t based on ignoring the reality of a world shot through with pain and suffering, the “chaos” of which the Outsider sees “too deep and too much,” as much of our “mind, body, and spirit” “positivity” is. He saw the world without a blindfold and took it neat, if I can mix my metaphors, maintaining the “bird’s eye view” that looked out on distant horizons of meaning, to the end.

Wilson died just on the cusp of the world getting, well, strange – or at least stranger than it had been. He passed away before Brexit, before Trump, before Covid-19, before Conspirituality, before the climate crisis became impossible to deny, and before the general ontological and epistemological crises that I talk about in some of my books set in, although these were indeed on their way.

A few years after his passing, my book about Wilson, Beyond the Robot: The Life and Work of Colin Wilson, appeared. As it turned out, my publisher had the rights to The Outsider and thought the time was right for a new edition, to which I contributed a new foreword. So the two books appeared at the same time. I was, of course, happy about this. But I admit I wondered if The Outsider would appeal to contemporary, younger readers, to whom names like Sartre, Camus, Hesse, and Dostoyevsky may not ring the same bells as they did for my generation and that of Wilson’s earliest readers.

Do Outsiders Still Exist?

Is existentialism anything more than a topic on someone’s philosophy exam these days? In our post-everything world, do Outsiders still exist, and do their challenges mean anything? If there are Outsiders out there, what are they doing?

Wilson’s answer to this, I believe, would be yes, Outsiders are still around. And I think he would add that they have never had it so good.

The Outsider’s problem is freedom. Not political or social or economic or sexual freedom – all of which are, of course, important. The kind of freedom that obsesses the Outsider is an inner freedom, a kind of inner expansiveness and deepening, that lifts him out of the confines of the present, and the limitations of his own personality, and makes him aware of the potentialities of life of which he is usually unaware. It is essentially a widening of consciousness and a strengthening of its grip on reality. Freedom, for the Outsider, is equivalent to reality. His moments of freedom are moments when he is more in touch with reality, and not the pasteboard substitute which he usually takes for that elusive commodity.

Yet, although these moments reveal to him a world of overwhelming meaning and complexity, of infinite interest, they are fleeting and no sooner is “reality” glimpsed, and he loses sight of it. This is why in The Occult, Wilson defined the central obsession of his work as “the paradoxical nature of freedom.”

Why is freedom paradoxical? Because when our freedom is threatened, its value becomes indubitable, and we will fight tooth and nail to preserve it. Yet, imperceptibly and involuntarily, once our freedom is secured, we begin to “de-value” it. It becomes subject to what Wilson calls “the indifference threshold,” a kind of automatic loosening of our grip on the reality of our freedom or any of our real values. We “take it for granted” and may even come to feel our freedom is a burden, something to endure until something distracts us from it, like the latest pablum on NetFlix. Hence Erich Fromm’s once-influential book Escape From Freedom and Sartre’s dour one-liner telling us that “man is condemned to be free.”

Dominant .005% & Self-Actualisers

Wilson’s subsequent body of work can be seen as an attempt to arrive at a method of inducing these moments of inner freedom, what the psychologist Abraham Maslow, on whose ideas Wilson draws, called “peak experiences,” moments of sudden, “absurd” joy and well-being. And we can also see Wilson’s work as a characterological study of the kind of people Maslow called “self-actualisers,” who are prone to peak experiences, and who share many traits with Wilson’s Outsiders, and with another demographic type, individuals whom Wilson calls the “dominant .005%.” All three have a need for this inner freedom in a way that most of their contemporaries do not, although in one way or another, we all have an appetite for this inner expansiveness, even if we satisfy it with the simple expedient of a glass of wine and a film.

But for these peculiar individuals it is a need as absolute as the need for food and other basic necessities. In fact, it is often greater than the need for these; more than one Outsider has faced starvation and poverty in his quest for the widening of inner space, just as more than one has succumbed to alcoholism or drug addiction in his pursuit of it.

Wilson tells us that the need for this inner freedom is an expression of what he calls the “evolutionary appetite,” the urge to grow, absorb experience and develop, and use our freedom, however clumsily, to gain more freedom. Wilson’s Outsiders and “dominant .005%,” and Maslow’s “self-actualisers,” are people driven by a compulsion to evolve, to gain deeper insight into and control over the mechanism of their own consciousness. And Wilson believed that since the nineteenth century, when Romantics first opened the gates to “inner worlds,” the number of people feeling this compulsion has grown.

Nevertheless, when The Outsider first appeared, the number of people interested in inner freedom was still relatively few. As Wilson soon discovered, because of his focus on existential questions – questions, that is, about meaning – and disregard for political and social ones, he was quickly branded a “fascist” by his left-oriented, “socially conscious” contemporaries. Yet it was with The Outsider and books like Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums and other Beat productions that the widespread popularity of a kind of grassroots “spirituality” began, with the importation of Zen and other forms of “Eastern wisdom” into the west. By the mid-1960s, the taste for lux ex orient had fused with the burgeoning psychedelic movement and “counterculture” to form a generation of “seekers,” dissatisfied with the increasingly materialistic character of modern life. The Outsider was in no small part responsible for the Hermann Hesse craze of the late 60s and early 70s, which numbered an adolescent me among its many adherents. By the end of the mystic decade, the beatniks who had been vaguely “on the road,” were now moving in a more purposeful direction, on a “journey to the East,” the title of a short novel by Hesse.

By now, the strange, threatening, “revolutionary” character of the “mystic Sixties” has become thoroughly domesticated, with yoga centres, “mind, body, spirit” emporiums, meditation classes, New Age bookshops, online Tarot readings, and any number of other “mystical” enterprises available at a click on the internet. Needless to say, not all of this is of equal value; a great deal is rubbish. Wilson’s generous view would be that yes, much of what is available today on the internet is junk and one must discriminate, but on the whole it is a good thing. Better a glut than a famine. And in any case, what differentiates the Outsider from his fellows is that he is “capable of a seriousness, a mental intensity, that is completely foreign to the average human animal.” Such a seriousness will have no problem separating the wheat from the chaff. The Outsider’s challenge requires him to ignore 99% of the chatter around him, to dismiss the noise and focus on the signal.

Obstacles & the “Indifference Threshold”

Wilson came to see that ultimately the greatest obstacle to the Outsider “becoming who he is,” to finding a means of expressing the creative energies within him, is himself. Not society, not the government, not the bosses, or his friends, but his own tendency to self-pity and laziness. He needs to overcome his own neurotic self-division, to arrive at a discipline that focuses the mind so that his grip on reality remains firm. He needs to find a way to avoid the “indifference threshold” that allows him to take his freedom for granted.

Wilson came from a working-class background and before his debut worked at dozens of menial and manual labour jobs. More than once he pointed out that compared to how things were for many of his Outsiders, people today have secure, comfortable lives. The welfare state, nationalised medicine, and other safety nets are in place. They may not catch everyone, but compared to earlier times, the general standard of living today means that most of us live practically like royalty of old – better, with the internet and other tech at our fingertips.

He points out that optimists, like himself, and two of his literary heroes, Bernard Shaw and H.G. Wells – socialists both, I might point out – tend to come from difficult backgrounds. They are forced to “pull their cart out of the mud” from an early age and so are less inclined to give way to despair. Pessimists tend to come from comfortable backgrounds and are spoiled and lazy. Wilson’s bête noire, Samuel Beckett, famously spent most of his time in bed because it struck him that there was no reason to get out of it. No wonder many of the characters are paralysed or in other ways unable to move. That his nihilist, absurdist plays were awarded the Nobel prize for literature is a sign, Wilson believed, that we have come to accept his pessimistic conclusions – “there is nothing to be done” – as given.

Maslow also pointed out that adverse conditions are often more favourable to “self-actualising” than comfortable ones. We are at our best when we are “up against it” when meeting a challenge. Calls for government support for the arts may be the sociological equivalent of giving fertilizer to weeds.

Wilson’s most important discovery in his analysis of the “indifference threshold” is that crisis or inconvenience seems to stimulate the mind out of its lethargy when even “positive” inducements fail to do the trick. We all know how difficult it is to cheer someone up if they are in a bad mood; even the most pleasant things won’t do it. Yet, more often than not, if suddenly faced with some difficulty they can overcome, the bad mood vanishes and the grumpy individual is now happy. The inconvenience has awakened his will, with the paradoxical outcome that a real problem cheers him up.

Wilson’s Outsiders instinctively know that “the comfortable life causes spiritual decay just as soft sweet food causes tooth decay.” That is why so many of them followed Nietzsche’s advice and “lived dangerously.” Wittgenstein gave away a fortune to live as a schoolteacher in some Austrian backwater. Sartre never felt as free as when he was working for the resistance and could be arrested by the Gestapo. Another example that Wilson often gives is of the writer Graham Greene, another pessimist.

Waking Up with Russian Roulette

As a teenager, Greene was so bored that he took to playing Russian Roulette to relieve his ennui. A minute before almost blowing his brains out, the world seemed so uninteresting that the only thing Greene could think of doing was killing himself. Yet, when he heard the hammer fall on an empty chamber, suddenly the world was positively exploding with meaning and interest, so much that the idea of killing himself seemed an absurd joke. Wilson points out that we have created civilisation to overcome inconvenience and eliminate crisis. Must we point a gun to our heads to enjoy it?

What had happened? According to Wilson, the prospect of blowing his brains out caused Greene to involuntarily concentrate, to, as it were, make a fist with his mind and thereby strengthen his grip on reality. When he heard the hammer hit the empty chamber, he relaxed and was suddenly overwhelmed by the reality that in his boredom he was ignoring. The meaning and interest of which he suddenly became aware were always there, but Greene was on the wrong side of the “indifference threshold” and so could not see them, just as a colour-blind person is oblivious to a blazing sunset, or a deaf person to the birdsong accompanying it. The process ran like this: sudden total concentration, then – completely relaxation. (As Doctor Johnson pointed out, the thought of one’s imminent hanging concentrates the mind wonderfully, an insight shared by the philosopher Heidegger and the esoteric teacher Gurdjieff.)

Wilson points out that the poet Wordsworth explained to his friend Thomas De Quincey how he wrote his poetry. One evening Wordsworth had his ear to the road, listening for the mail cart, when he suddenly caught sight of a star, which struck him as extraordinarily beautiful. He then told De Quincey the secret of his poetry. It was that whenever he concentrated on something that had nothing to do with poetry – like listening for a mail cart – then suddenly relaxed, the first thing he saw always struck him as beautiful.

Wilson realised that not only had Wordsworth revealed the secret of his poetry, he also hit on a means of inducing peak experiences. Readers of Wilson will know that all his work is essentially aimed at spelling out the significance of Wordsworth’s observation, and of developing methods of putting it into practice.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

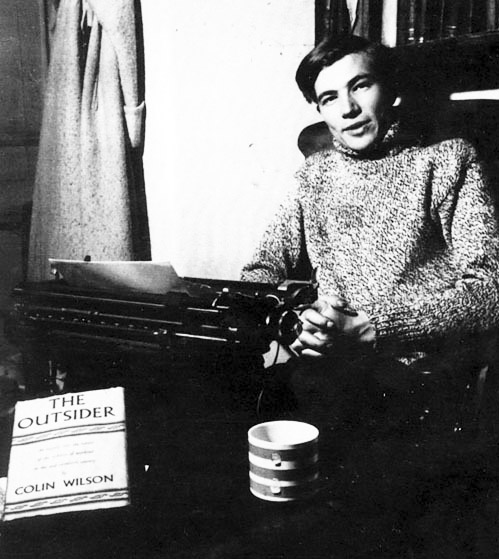

What of the characterological types, Maslow’s self-actualisers, Wilson’s Outsider and his “dominant .005%”? Maslow believed that our need to grow, to develop – what Wilson calls our “evolutionary appetite” – is as basic as our need for food or sex. He developed what he called a “hierarchy of needs” to help understand human motivation. At the bottom is the need for food. Once this is satisfied, our need for shelter, a home of some sort, kicks in. When we have achieved this, we feel a need to share it with someone, that is, for love – and sex. The next need to awaken is what Maslow calls the need for “self-esteem,” the good opinion of others. These first four needs Maslow called deficiency needs; they are for things we lack. At the top of his hierarchy, Maslow put the need to “self-actualise,” to “become who we are,” to make real our potentials, to use our creativity and intelligence. This is a need to use what we have.

Maslow believed that we all have these needs. But toward the end of his life, he was troubled by the observation that not everyone reaches the top of the hierarchy. That is, not everyone self-actualises. Many people seem happy to remain at the self-esteem level and do not feel the need to be creative. In Wilson’s terms, they do not feel the pangs of the “evolutionary appetite” so painfully as his Outsiders do. Nevertheless, a substantial percentage of the population do feel them and work toward “actualising” themselves.

Wilson’s “dominant .005%” share some characteristics with Maslow’s “self-actualisers.” Wilson learned from the writer Robert Ardrey, author of The Territorial Imperative, that “dominant” individuals make up 5% of all animal groups. This is also true of humans. The human dominant 5% comprises politicians, pop singers, sports figures, film stars, television personalities, high profile academics, successful businessmen, internet influencers – just about everyone who displays “natural” leadership qualities and has “push” and “drive” and perhaps a bit of talent; it also includes not a few criminal types.

Wilson discovered an interesting thing. This dominant 5% does not include the most dominant characters. They make up only a minute fraction of the population, .005% perhaps. These individuals share something with Maslow’s self-actualisers, just as the dominant 5% share something with his “self-esteemers.” Both the self-esteem oriented individual and the dominant 5% need other people; the one for his good opinion of himself, the other to express his dominance. Without others, they are lost. The ruthless businessman is not so impressive without his anxious underlings, just as a pop star without ogling crowds seems absurd. Without those around him patting his back, the self-esteemer is at a loss. Yet both the self-actualiser and the .005% are free of this liability. In fact, for both, other people are often a problem.

The .005% and “self-actualisers” pursue creative activities for their own sake, for the sheer challenge and joy of it, for the inner expansion that accompanies creative work of any kind. Yes, the artist wants his paintings seen, the writer his books read, and the musician his music played and appreciated. But they do not paint, write, or compose for that reason, at least the real artist, writer, or composer doesn’t. They are less influenced by their personal needs than they are by impersonal ones, i.e., the urge to grow beyond their personalities, into the realms of objective meaning and reality. Into, that is, that reality that the Outsider glimpses in his moments of power and strength.

In his study of crime, Wilson makes some interesting use of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, seeing it as a way of understanding the changing character of murder over the centuries. I can’t go into detail about this here, but the basic idea is that in the twenty-first century we have entered a strange era in which the self-esteem murder – the murder in which the killer “becomes somebody,” with his name in the news – common to the late twentieth century, has shifted into murder as a warped form of creativity, the strange seemingly “motive-less murder.” This, indeed, seems a rather dark way of recognising a society’s psychological growth. But I think we can apply the same idea in a perhaps less gruesome area, that of social media.

An Evolutionary Leap?

I submit that, at least in the developed world, society as a whole has entered the self-esteem rung on Maslow’s hierarchy and that the evidence for this is social media. Here we compete for “likes” and “friends,” and draw attention to ourselves in any way possible, hoping to stand out for a few moments in the “stream” of everyone else doing exactly the same thing. Otherwise mediocre personalities become “influencers” and Instagram stars at the tap of a phone. Yet this may be a good sign. Because if Maslow is right, it means that there are quite a few self-actualisers out there who are too busy satisfying their evolutionary appetites to bother tweeting about it or to ask for their friend’s approval. Along with the .005%, they are quietly working away at “becoming who they are” and aren’t concerned if anyone knows about it. They are Outsiders whether they have ever read Wilson or not.

I also believe that just as elementary particles no longer in contact with each other continue to behave as if they were – through the miracle of quantum entanglement – and just as neurons in the brain involved in the same operations fire at the same time, although they are not contiguous, the people making up Maslow’s self-actualisers, Wilson’s .005% and Outsiders, spread out all over the planet, act, in someone unknown to them, in a similar manner. They may not know each other – most likely they are too busy to get acquainted – but their individual actions may add up to something that transcends their individual situation. And that may be the evolutionary leap that Wilson firmly believed was on its way.

Gary Lachman