The Serpentine Mysteries of Ireland

By Jonny Enoch & David Halpin

Many will flock to local Irish pubs on March 17thfor St. Patrick’s Day to celebrate the feast of a 5thcentury Christian Bishop who is famous for chasing the serpents off the Emerald Isle. Bars everywhere are adorned with green shamrocks and packed with rowdy crowds, singing and dancing an Irish jig while spilling green beer all over the place. Historians are quick to criticize this 17thcentury holiday by pointing out that Patrick himself was never very influential in his day compared to the Christian version of the story written about in the hagiographies.

This wonderful time of the year has evolved into more than just another Catholic holy day and is all about celebrating the magic, mystery and lore of Ireland. Therefore, we must ask ourselves, could there be an even deeper meaning to the legends of St. Patrick?

First of all, we know that Ireland never really had any snakes to begin with, as this symbolism was later adopted into the story to refer to the persecution of pagans, whom were not evil by any means, but their name is derived from the “Pagani”, which just means country folks or nature worshippers.

To the ancient religions of the world, the serpent represents wisdom and energy. According to the great esoteric historian Manly P. Hall, America was never named after the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci, but was derived from the serpent god of Peru, Amaru, with “Amaruca”, meaning “Land of the Plumèd Serpent”. This is also true of the mythical island of Atlantis, which was known to the Arab geographers as “Antilla” or “the Dragon’s Isle”.

The initiates of the mystery schools knew how to tap into this energy and were often called the Serpent-kings. The druids, from which Freemasonry is derived, were the priests of the sun and served a nature god in a crossed-legged or meditative position, who much like Krishna in the Hindu traditions, was symbolically portrayed holding a serpent in his hand and was known as Cernnunos or Hu-Gadarn. From the latter is from where we get the name Hu-mans.

In fact, the connections between the Emerald Isle and India are so eerily similar, we are told that the ancient and mythical race of the Tuatha Dé Danann arrived in Ireland on flying ships, much how we hear about the Vimanas or flying machines of the Vedas. We can also link Ireland to Egypt with a story we get from the Scottish chronicler Walter Bower about a princess named Scota, who was the daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti. According to Bower, both Scotland and Ireland were named after her, as the ancient name for Ireland was Scotia. We also find that the Celtic harp is similar to the ones portrayed on the reliefs of the walls in ancient Egypt, which is mysteriously attuned to the Hertzian frequencies of the music of the spheres or the planets.

The Hill of Slane and Tara County Meath

The Hill of Slane and Tara County Meath

The serpentine energy of the mysteries is divided up into three different categories, one being Bio-electrical with the rising of kundalini up the thirty-three vertebrae of the spine, just like the thirty-three degrees of Scottish Rite Freemasonry, and opens up into swan wings on each side – or the equilibrium of the brain – represented by that all too familiar symbol on the side of our ambulances known as the Caduceus of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus. We see the merging of the pineal gland at the top of the staff, also shown as that pultruding serpent from the third eye of the headdress of the Egyptian king.

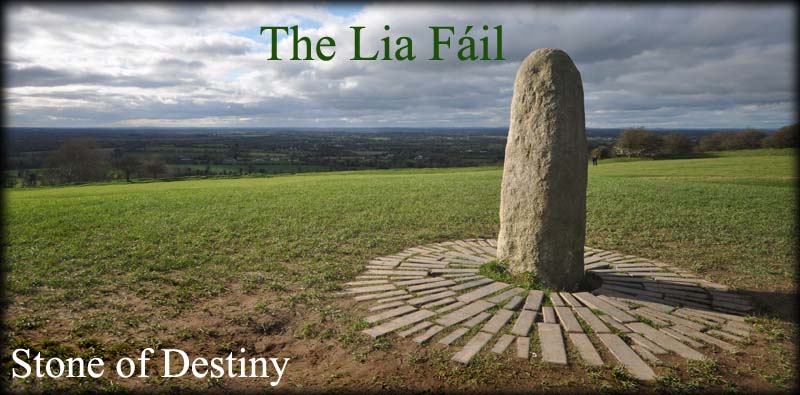

Another type of serpentine energy is Geo-Magnetic, which we find with ley-lines and vortices around the world and were well documented by Dr. Ivan Sanderson in 1972. Many megalithic temples with obelisks and pyramids have been built on the 33rdparallel and places of great energy. Ireland is of no exception with its countless haunted castles and churches scattered across the country. Many are drawn to Ireland’s sacred sites like New Grange, which was built by the Neolithic peoples to align its crux-shaped chamber to the rising sun on the week of the winter solstices; and the Hill of Tara, topped with the Lia Fáil, or the stone of destiny.

When we examine Stonehenge on the Salisbury plane of England, we find 900 similar megalithic henges with astronomical calendars and solar alignments that lead all the way up to Nabta Playa in Egypt. There are shocking similarities with the latter and Boleycarrigeen Hill in Ireland, as they are similar in design and both have connections to a sacred cow. This might be attributed to the Hindu age of Taurus in the Yugas or the Precision of the Equinoxes, which is symbolized in our ancient religions with Moses destroying a golden calf and Mithra ripping the head off a bull.

“Jonny Enoch and David Halpin standing in front of a stone circle in Ireland”

“Jonny Enoch and David Halpin standing in front of a stone circle in Ireland”

Finally, there is a type of Universal and invisible serpentine energy, which the Theosophists called Fohat, the German secret societies called Vril, Tesla called it scalar, and we now refer to it as zero-point energy. Could these ancient places of power operate alongside the geomagnetic properties of the earth like a worm hole to other dimensions? Did the ancients understand a secret science capable of allowing them to become the walkers between worlds and interact with invisible inhabitants?

Our scientists tell us that matter, space and time can be bent, warped and twisted back into itself to form a worm hole to travel into other dimensions. This is not unlike reports we’ve heard about people going missing in faery circles and there are countless reports of strange occurrences taking place inside of crop circles, healing circles, séance circles and more.

The concept of multiple realms is found in all indigenous traditions and the belief that the soul separated into various parts upon death makes interesting food for thought. This is especially true when thinking about the fairies in Irish mythology and how those abducted to ‘fairyland’ were often both here in the earthly realm as well as in a completely separate spiritual dimension.

We might also see parallels to the tripartite souls and the belief that ancestors were still occupying certain sacred places as well as being in a separate spiritual realm. Another often overlooked aspect here is the lack of differentiation between a deity of the Otherworld and the Otherworld itself.

It should be noted that many early traditions speculate about a whole eco-system of consciousness and where exactly fairies fit into this is certainly open to question. A good example is noted in the Mandaean cosmology of four worlds: the Light-world, the world of darkness, our own material world, Tibil and the world of ideal forms and the spiritual counterpart to our own world, the Mshunia Kushta.

It should be noted that many early traditions speculate about a whole eco-system of consciousness and where exactly fairies fit into this is certainly open to question. A good example is noted in the Mandaean cosmology of four worlds: the Light-world, the world of darkness, our own material world, Tibil and the world of ideal forms and the spiritual counterpart to our own world, the Mshunia Kushta.

It is from the Mshunia Kushta that angels, demons, heavenly doubles, and fairies emerge. This idea that a person can be physically present yet their consciousness be in another realm entirely is also vary apparent in Asian shamanism.

Our earliest myths are full of fairy encounters even if they sometimes are known by different names. To lose track of this fact is to disconnect with the more primal root when it comes to these forms. And yet, we are literally dealing with, and tentatively engaging towards, a whole eco-system of consciousness. Who is to say that it has always been the same manifestations all along?

Perhaps the cosmic drift of time outside of our own perceptions brings us into contact with new tides of consciousness which interact on, and from, a completely different part of our sensory and electromagnetic spectrum. If this occurs will we even have the ability to recognize the interaction?

Perhaps every single human being and our individual metabolisms ‘dial-up’ a different frequency and we are never dealing with the same archetypes at all?

Many are surprised that the common belief that Irish fairies are the banished Tuatha Dé Danann is not as clear-cut as some accounts would have us believe. In fact, in Irish mythology it is implied that the aos síwere already here before the Tuatha were said to have retreated into the mounds and fairy forts.

In this case it would mean that the fairies were separate from the later Gods of Irish lore. The potential twist here is interesting, though. The Tuatha Dé were said to have arrived in supernatural circumstances themselves, emerging from clouds of mist, so perhaps this could be explained as them arriving from a fairy realm in the first place?

Fairies, in another of their incarnations, are linked to nature spirits and supernatural beings connected to particular aspects of landscapes. This is not specific to Ireland, of course. All around the world areas considered sacred or magical are said to be the homes of spirits. From New Zealand to North Africa, from Tibet to Peru, natural features and elaborately constructed and aligned monuments are considered the abode of elementals and supernatural deities.

However, this does not mean that they are tied to one place, outside of our own understanding. As Claude Lecouteux writes in his book, Demons and Spirits of the Land, “…the syncretic nature of these creatures has conferred upon them specificity so strong it conceals their origin.” (P. 133).

However, this does not mean that they are tied to one place, outside of our own understanding. As Claude Lecouteux writes in his book, Demons and Spirits of the Land, “…the syncretic nature of these creatures has conferred upon them specificity so strong it conceals their origin.” (P. 133).

After Christianity came to Ireland, the fairies developed a more sinful origin in newer folklore and a spiritual context influenced by a monotheistic point of view.

The ambiguity of their actions meant that the good people always occupied a type of neutral space between something that could benefit and something that could harm, but now those outcomes were more simply defined as good and evil.

The fair folk, depending on who you asked, might be agents of either side. This notion stemmed from a variety of beliefs which even today makes for interesting conversation.

The easiest way of framing this is that fairies were seen as existing in a type of ‘not quite evil enough for hell, not quite good enough for heaven’ state. Some Christian stories even explained them as fallen angels who had rebelled against god but then regretted their actions.

These stories seem to contain the subtext of an attempt to subjugate pagan gods and spirits into a Christian interpretation of the universe.

In his landmark compilation, The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries, W. Y. Evans Wentz, tried to examine fairies from new anthropological perspectives as well as collecting first-hand accounts of encounters with the good people. One of the most complex areas Wentz questioned was whether or not fairies, ancestors and the dead were the same. Did a person who died become a fairy? Were there specific actions or circumstances that made it so?

Or, was it a trick by the good folk and they took the form of dead loved ones in order to influence? Alas, this area is both thorny and controversial. There are indeed arguments for a crossover at times, but this is linked strongly to the perspective of the person or culture at the time.

Or, was it a trick by the good folk and they took the form of dead loved ones in order to influence? Alas, this area is both thorny and controversial. There are indeed arguments for a crossover at times, but this is linked strongly to the perspective of the person or culture at the time.

Finally, the explanation for fairies which many contemporary scholars and writers seem to favor is one that fits perfectly with the contradictory nature of these beings. In this view, fairies take on the cultural forms most prevalent to those they appear to.

So, the angelic and demonic forms fit the myths and lore of ancient times, for example. Are they aspects of our collective unconscious or even psychological manifestations leading us further into timelessness and non-material aspects of ourselves? In this view, as we move through the centuries, art, religion and writing begin to influence how these beings are perceived.

As we became more and more embedded in technology and urbanization, fairies became aliens and inter-dimensional travelers. Now, if you are unfamiliar with this topic the comparison might seem odd but, in fact, there are many places where striking similarities emerge.

Fairies and aliens both kidnapping for midwife purposes is one, changelings replacing human children and spinning bright lights resulting in missing time are others. The writers Jacques Vallee and Terence McKenna have written extensively about this subject. So, as you can see, the concept of who the good people are *seems* to become more complex as time moves on.

But is this really the case? Perhaps fairies have always stayed the same and it is us who change and grow, allowing us to comprehend a little bit more of the whole picture with each new generation. Then again, maybe we will never discover who the fairies really are and this is the way it is supposed to be; to hold mystery close to our hearts and to continue to imagine and believe in something other than ourselves.

—

Why not find out for yourself about megalithic mysteries, faeries and ancient Irish lore by joining Jonny Enoch, Brien Foerster, David Halpin and Anthony Murphy on the

Mythical and Mysterious Tour of Ireland

https://www.authenticvacations.com/mythical-ireland/

Come Follow Us on Twitter – Come Like Us on Facebook

Check us out on Instagram – And Sign Up for our Newsletter