|

|

…a man not forestalled by predecessors, nor to be classed with contemporaries, nor to be replaced by known or readily surmisable successors – W. M. Rossetti …a man not forestalled by predecessors, nor to be classed with contemporaries, nor to be replaced by known or readily surmisable successors – W. M. Rossetti |

|

|

|

When I was five years old I came across a book of English verse that was to have a tremendous effect on my life. I don’t remember the title but it was a collection of great poems by numerous British writers from as far back as Chaucer up to the late Victorian Age and into the early twentieth century.

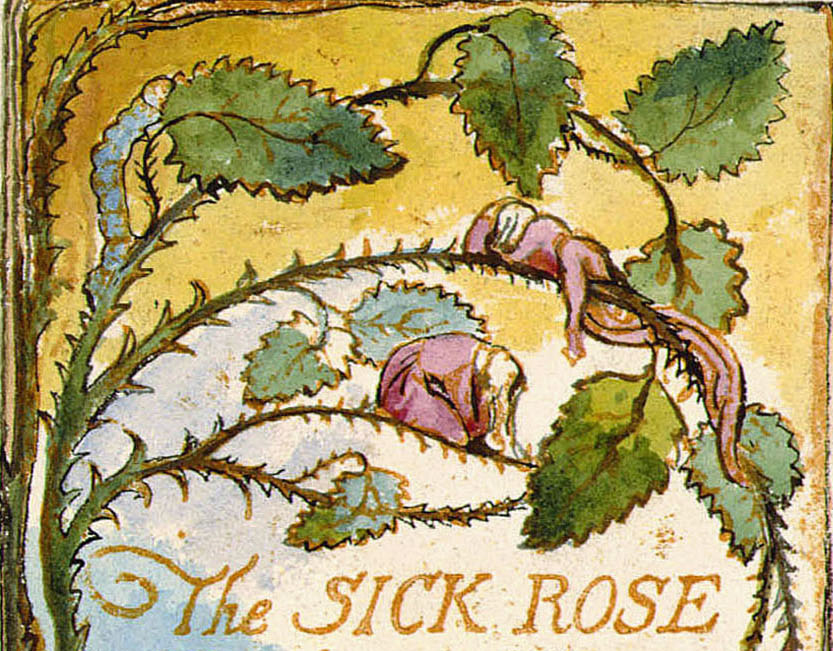

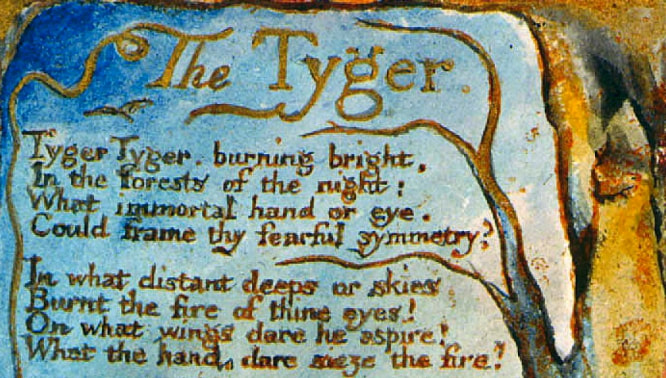

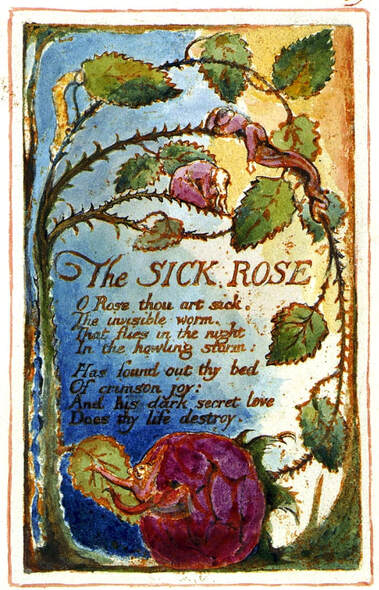

Toward the end of the book were poems by Thomas Hardy, Matthew Arnold and Gerard Manley Hopkins, etc. I don’t think modern poetry was included. At least I don’t remember seeing poems by T. S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, Ted Hughes or Sylvia Plath. Near the book’s center were a few poems by William Blake. I recall seeing his famous poem The Tyger, and less known shorter poem The Sick Rose. It was my first introduction to Blake and his visionary work. Since the book was second hand, it contained margin notes here and there. These were tiny and faint, as if made by a woman’s hand. Obviously the book had been used in a class on English literature, and the lines and stanzas marked while in class or while doing homework for a degree in the subject. Nothing too strange there. I wish I could remember what the previous owner found interesting about Blake’s work, or what the notes actually said. But it was too long ago, and the book has long since vanished. I do remember liking both poems, although I understood absolutely nothing about what they meant, if anything. It was the striking imagery of The Tygerthat captivated me, as it had done for many millions before me. The Tyger is the poem featuring the famous allusion to “fearful symmetry,” which succeeded in puzzling and entrancing so many imaginations, spurring all sorts of people to interpret its meaning. After all, what is so similar between an innocent lamb and rapacious tiger? Aren’t they normally figured opposites? What is Blake’s point? Was he deluded or just waxing lyrical? One might think his writing somewhat childish if it were not for the fact that Blake was one of the world’s greatest poets. |

|

|

|

Well, in my case it would be over three decades before the light began to shine, after half a lifetime spent deciphering Blake’s exact meaning. The two poems in the little compendium not only captivated my imagination, but obsessed me. I don’t know why.

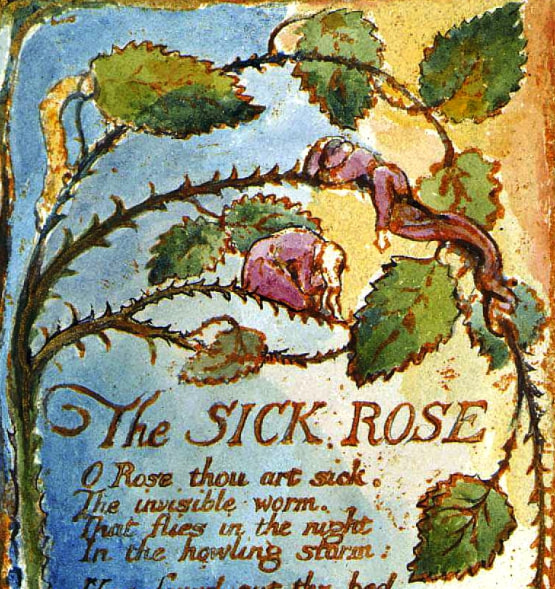

As in the case of The Tyger, it was the imagery in The Sick Rose, that not only held my attention but made me rate it so highly. Here it is: |

|

|

|

O Rose thou art sick.

The invisible worm, That flies in the night In the howling storm Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy: And his dark secret love Does thy life destroy.: |

|

|

Almost every line contains enigmatic and even sinister allusions. It is certainly surreal, haunting and puzzling. Its meaning is not clear on the first or second reading. Indeed, as many scholars have noted, it is a quite a challenge working out exactly what Blake meant us to deduce from the cryptic poem.

Since the poem’s appearance, numerous interpretations have been given, none being wholly sufficient. Things are complicated by the first line’s allusion to a rose. So common and equivocal is the symbol and metaphor of the rose, in art and literature, that it taxes one’s mind to decide which application Blake intends. Is his theme love? Is it romance, passion, friendship, relatedness, chastity, lust or perversity? Is he referring to sacred or profane emotions and aspirations, and if he intended using the rose as a metaphor, why be so enigmatic? The first line indicates that the rose is “sick” or unhealthy in some way. Perhaps it is in its dying moments, which means Blake’s thoughts are on autumn and winter, when all nature goes through a temporary cycle of dissolution and mortification. Is his allusion to a sick rose a comment on death? After all, rose is an anagram of eros, the opposite of which is thanatos. Life, death and everything in between – the big themes of high art. Those familiar with the poet’s work know that he does indeed dwell on themes of life, death, immortality and conflict between good and evil. Normally the symbol of the rose is associated with purity, love and divine ardor. However, Blake might be employing the imagery of a dying rose to express his cynicism about spiritual ardor, not to mention worldly love and attachment. He was a practically destitute married man approximately 37 years old when the poem first appeared in published form. After years of creative struggle he was at the peak of his spiritual maturity and insight. Perhaps he was having relationship problems or in some other state of mind doubting the pursuit of material success, sexual satisfaction and domestic bliss. Was he doubting the value of what most humans desire and cherish? Like the later writer, Thomas Hardy, did Blake see human love as something fleeting and insubstantial? Again, was his mind preoccupied by the problem of decay and death? Things get even more mysterious and complex when we get to the second line. The poet mentions an “invisible worm” that flies in the night in a howling storm. One is taken aback by the striking imagery, realizing at once that the poem is neither childish nor superficial. It clearly expresses metaphysical themes. Who or what is the invisible worm? Of the numerous interpretations out there, which one is correct? Is the worm Satan? Is it some dark force sent by Satan? Or is it something bestial within man? Does it represent perverse thoughts and emotions? After all, the “howling storm” works well as a description of the mind, particularly one in turmoil. Is the worm a particular kind of thought or emotion? Is it explained by a Freudian interpretation, being man’s base animalistic instincts? How would writers of the eighteenth century reference the wild instincts held in check by society? Indeed, there is much in The Sick Rose to suggest a psychological theme. Some commenters believe the poem simply refers to man’s destructive behavior toward nature. The image Blake painted to accompany the short poem lends credence to this idea. Perhaps the rose represents the whole of nature, bowed low and sickened by the baneful presence of the human world. A great many scholars accept this interpretation of the poem. |

|

|

|

The poem first appeared in print in 1794, when Blake was approximately 37 years of age. It was included in his book Songs of Experience. Most readers tend to see the poem as a simple comment on how goodness and beauty suffer desecration from unholy envious forces. But did Blake have something more complex in mind? After all, why are the beautiful and virtuous so vulnerable and subject to violence and destruction? Should they not be invincible and eternal?

|

|

|

|

As said above, the rose often symbolizes purity. With this in mind, does the poem refer to temptation and spiritual corruption? Does it deal with one’s loss of faith or collapse into sexual turmoil?

Does it tell us that Blake had lost interest in youthful pursuits? Was he no longer enamored with frivolity and sensual gratification? Or had he become disheartened with the sorry condition of the world around him; the poverty, ignorance, class conflicts, enslavement to authority, chicanery of educational edifices and social hypocrisy, etc? Did he feel that the chances for authentic human improvement had slipped by to be replaced by a facade of change and progress? Or was it something in his personal life that overshadowed his mind, such as his failure to become well known or disappointment at the resistance and interference he endured from inferior minds? Lines 1 and 2 tell us of a wasting rose, a thing of immense beauty apparently infected by a sullen worm. What do we deduce from these opening lines? Possibly Blake wants us to remember that every beautiful thing eventually decays, and that the cycle of natural necessity ordains what comes to pass in the world. No human being can avoid decay and death, no wise, no how. Additionally, there is, as we know, evil in beauty. The beautiful and virtuous are not immune to it, and can’t avoid coming up against evil and ugliness. Evil thoughts haunt those with perfect looks and manners, tempting and entrapping the holiest men and women. Evil is there within one’s psyche as it is in one’s environment. The question of why has preoccupied philosophers and thinkers from before Plato’s time, and many are the theories concerning it. In nature, flowers along with every living thing fall prey to predators, infections and blights. Even without human interference, creatures frequently suffer and die painfully. Trees fail to blossom, fields lay waste while newborn animals are seized and devoured minutes after taking their first breaths. What then, we are driven to ask, is the constitution and purpose of innocence and beauty if they prove so fragile and short lived? On a deeper level the poem seems to dwell on the belief that beauty plays a large part in its own destruction. Is there something about the beautiful rose that attracts violent and destructive forces? Is there something about morality that attracts temptation and testing? One is compelled to think so. Or do we prefer the simpler answer, that the worm flying through the storm in the night just happened to accidentally alight on the unfortunate rose? Actually, the infecting worm isn’t altogether normal. It isn’t found in the soil from which the rose grows but flies in the night in the howling storm. In this aspect we have an image that takes us into a different dimension of analysis. Is this the Edenic serpent? Is it the “feathered serpent” of mythology, akin to the seraphim perhaps? Is it the wise serpent spoken of by Jesus in the Book of Matthew? But why would a wise serpent bring decay and ruin to an innocent, beautiful rose? |

|

|

|

The great worm of Genesis isn’t depicted with wings. And if the invisible worm is a force of evil, why does Blake speak of its “love?” How can evil possess love of any kind, dark, secret or other? What was Blake up to?

|

|

|

|

Perhaps the poet wanted to draw our attention to the underlying metaphysical reasons for death and decay. After all, would we even appreciate and contemplate beauty if it were not so transitory? The stars above our head every night go almost completely unnoticed. However, if they appeared before us but once a year, would not the people of the world stop what they are doing and stream forth from their houses to marvel?

Man makes things in the world around him invisible by proximity. He easily takes things for granted and allows his senses to be dulled into indifference. Blake may have wished to remind us that to acknowledge death and decay presumes we also notice their opposites, and that it cannot be any other way. To note the condition of the sick rose presumes we’ve also marveled at its splendorous form and fragrance. But again, Blake may have wanted to address what it is within beauty itself that causes its demise. What is it within the virtuous that attracts evil? Why are the good, honest, noble, faithful and brave so accosted, obstructed, challenged and undermined? Perhaps there is something overly naive about their outlooks, something deficient in their understanding of evil. |

|

|

|

The Sick Rose reveals that Blake understood the lineaments of sado-masochistic love long before Freud was born.

|

|

|

|

Why do we get from the opening lines the sense that the rose is not only sick but relatively defenseless? The imagery describing the worm stresses its strength and purposefulness. Since both the rose and worm are creations of nature, how can the latter be exempt from decay and death? Does Blake believe that evil is stronger than good? Is he telling us that objective evil exists to prey on the world? Is he advocating a Christian explanation of how such deep set corruption comes to be, or does he have an alternative account of evil’s existence?

On a subtler note, the poet has incorporated comment on the perspective of the beholder. Who is it that stops to address the rose’s condition and predicament? And is that spectator part of the evil and decay? Maybe it’s all about perspective. After all, who observes the activity taking place and comments on the apparent antipathy between rose and worm? And might not their perspective be biased, insufficient and erroneous? The first line is a declarative proclamation from an observer: thou art sick. The narrator seeks to diagnose the condition of the rose. But we ask whether his perspective is accurate and conclusive. What does man really know about nature and its cycles? What about less obvious underlying conditions and structures? Is it rational to stand back from the world and pontificate indifferently about cycles from which one feels separate? Does Blake want us to catch ourselves in this mode and realize its absurdity? Is he saying that far from being detached spectators, we are very much part of the natural cycle, gaining nothing by denying our corporeality? Is the cycle of the rose not the cycle of Man? With this in mind, the poem might subtly address our fear of death. Is it our dread of death that constitutes the sickness mentioned? Is fear the infection brought by the worm, something so crippling to the will that we have difficulty blossoming as we should? Blake had very distinct ideas about man’s role and purpose, and had much to say on the necrophilous forces inhibiting man from fully expressing his being. |

|

|

|

Blake was familiar with the ideas of a few European mystical thinkers, and may have been familiar with Angelus Silesius’ comments about the rose in his poem The Puckish Pilgrim:

|

|

|

|

The rose is without ‘why;’

It blooms simply because it blooms. It pays no attention to itself, Nor does it ask whether anyone sees it. |

|

|

Particularly striking is the third line: It pays no attention to itself. Echoing Meister Eckhart (the earlier mystical thinker) Silesius correctly articulates the way it is with natural forms. A cloud crosses the sky. Does it leave a trail? Does it “think” about what it’s doing? Does it intend to appear and move as it does? No, but it’s there nonetheless. It has substance and corporeality nonetheless. What it lacks is an ego, a self-reflexive identity and self-awareness. Does this mean it is in some way incomplete in terms of being? If the rose or cloud were less or more of themselves, they’d cease being exactly what and as they are. As Blake elsewhere wrote, if the sun and moon should doubt, they’d immediately go out.

The poet notes this will-less will, this mysterious presence of being so precisely attuned to the cosmic order. The Taoist long ago recognized the egoless movement of nature, calling it the Mysterious Female and frequently referring to it as Wu Wei. Is this a million miles away from Blake’s rose, which accepts its fate without resistance? Nowhere in the poem does the rose complain about the presence of the worm, nor does it resist its fate. We are asked by Blake whether Eros can be Eros without Thanatos, its opposite. Can life be life without death? Silesius’ final line stresses the point, highlighting the presence of beauty in and of itself, eternal and self-instantiating. It’s incongruent to human thinking which contradicts the natural way. We always notice our appearance and other people’s gaze. We are always obsessed with fitting in, going along with the crowd, not rocking the boat and receiving acknowledgement and approval. We can hardly do otherwise. We’d find it nigh on impossible to be as the rose described by Blake and Silesius. We talk endlessly about perfection, beauty and peace, but does not the rose already exemplify these? Without consciousness of itself is it not freed from misery? Is it not without lack and pangs of desire? Although from a human viewpoint the serene rose may be an object of desire, the flower itself is apparently free from desires of its own. It simply exists, and in doing so reveals to us much about existence. This perfect state of being is probably alluded to by Blake’s fifth and sixth lines: Has found out thy bed of crimson joy. The rose is apparently rooted in peace and harmony. It is ecstatic and content to simply dwell and be. So much so that it does not resist contamination from the worm. Its destruction is in this context a delusion, its death not as human death. Living each second so fully and authentically, no external force can take anything away from it. The rose can never experience lack or desire for more. On the contrary, the rose’s giving up of its beauty, serenity and fragrance is the proof of its unfathomable plenitude and abundance. The rose’s destruction is, therefore, more correctly a matter of human perspective. Clouds pass over the sky to finally dissipate. Do we think of them as dead clouds? Stars in the heavens vanish from view. Do we notice or care? Are we aware of the thousands of deaths occurring around us every day? Do we notice how we age over time? Given that Blake was thinking about autumn and winter, we ask if we don’t see beauty in the fallen leaves or glistening snow-blanketed landscape? Of course we do. So is there really less beauty in a dying rose than one in full bloom? If ugliness exists, might it not be in the agent of destruction, the worm? In this case, is not the poem a comment on the relationship between beauty and ugliness? But as said above, do not all life-forms arise from the same soil of nature? How then can the worm hearken from some other origin than the rose it destroys? And if both rose and worm share the same origin, must not one bear within itself characteristics of the other? Must there not be a hidden underlying unity? In Freudian parlance, is the worm to be associated with Thanatos (the Death Instinct)? Maybe, since rose is an anagram of eros, meaning “life.” In Greek mythology Eros is a god representing creativity, passion and romantic love, or as Blake might have preferred to envision it, selfish love. In this sense it is a devouring narcissistic desire or love not wholly concerned with the existence and need of the other. Is this the meaning behind the line “dark secret love?” In his poem The Clod and the Pebble, Blake spoke of narcissistic love: |

|

|

|

Love seeketh only Self to please

To bind another to Its delight Joys in another’s loss of ease And builds a Hell in Heaven’s despite |

|

|

Alternatively, it may simply be that the rose’s sickness is cured or healed by the presence of the worm. In this case, Blake may be alluding to the inescapable fact that although individual things die, life itself never does.

If the rose’s inherent narcissism and unwholesomeness attracts its own destruction, the worm can no longer be seen as an agent of evil but of harmony, bringing an end to the rose’s narcissism and one-sided desire. From this perspective the rose’s splendor is akin to the plumes of a peacock seeking to bedazzle and lure a mate. It is a profane rather than a sacred beauty. In some of Blake’s writings he occasionally construes the whole of nature as deceptive and treacherous. If the rose represents nature as a whole, Blake’s poem must indict nature as falsely embodying and exuding beauty. Nature, in this case, exudes an alluring kind of beauty in order to entrap souls, or bring out of them profane desires. The rose’s beauty, therefore, perpetuates delusion and superficiality. In any case, the allusion or warning pertains to the allure of false self-serving beauty. The worm’s destuctiveness (“his dark secret love”) is therefore awakened and activated by false beauty. This throws quite a different light on the poem’s meaning. Backing up this interpretation is Blake’s use of the term “crimson joy.” The color red is often associated with lust, allure, enthrallment and sexual debauchery. Its usage qualifies our point about false beauty and false love. Blake appears to be referring not only to cosmetic appearance, but underlying intention. Beauty certainly exists, but what, he asks, is its object? Does a person’s physical appearance lead them and others toward virtue or vice? By way of a beautiful man’s or woman’s appearance, grace and elegance are other people inspired or brought low? Is not the misuse of beauty and sexuality something vile? Can it not lead to utter ruin? |

|

|

|

How do we tell the difference between sacred and profane love, between adoration and obsession?

|

|

|

|

If this is Blake’s thought, we see that he did not share the ancient Grecian idea that where beauty is, goodness is sure to be. On the contrary, Blake seems to say, where beauty is, evil is more likely to be found.

|

|

|

|

Blake drew and wrote to reveal spiritual truth. Spiritual truth does not lie on the surface of appearances: indeed, it is often contradicted by appearances, and where Blake found that contradiction he did not scruple to sacrifice the apparent fact for unapparent truth – Max Plowman

|

|

|

|

Taking up this controversial perspective on the poem’s essential meaning, it may be that Blake referenced a rose in an effort to direct us to the mythical concept of Sub Rosa or “Under the Rose.” For ancient occult societies this term encapsulated the perverse relationship between the goddess Aphrodite (Venus) and her child Eros, god of love.

The rose was not given to Eros virtuously. It was a present meant to keep him quiet about his mother’s promiscuity. Eros was to “keep silent” about her sexual antics. Consequently, the term Sub Rosa and the rose symbol denote an immoral pact between mother and son or any other persons. Both parties agree to remain silent about immoral or amoral behavior. The rose, therefore, often symbolizes collusion, silence and deception, as well as the desire to deliberately if surreptitiously sanction evil, self-serving behavior. We see from this that Blake’s bowed sickened rose therefore represents the entire history of human vice, and all acts of immorality committed through time. It is a flower bowed over with the weight of sin. Given that this was Blake’s vision and reason for the poem’s mere thirty four words, we see that he did not regard the sick rose as a virtuous flower. Its beauty perversely conceals allure, mystique, hedonism and debauch bereft of shame and contrition. Again, the theme concerns narcissistic intent and pleasure-addiction lurking behind a veil of virtue. In this case the invisible worm represents a strange supernal force immune to the mystique and allure of false beauty and false love. It seeks out the venal in order to restore truth. Its “dark secret love” is now understood as a goodly love aligned with the cosmic order. The worm’s acts of destruction are needed to cleanse the soil, so purer specimens can take root and grow healthily toward the sun. In this sense The Sick Rose is about metaphysical sublation and alchemical transmutation. |

|

|

|

Given that this analysis holds, we see that the poem issues a warning to the venal and impure. Keep on the way you’re going and you will surely awaken forces which will one day circumvent your destructive nature. As venality hides behind a veil of silence, so do the forces of thanatos and catharsis work at the behest of a deeper silent unknowable force.

Blake seems to say don’t lament the passing of false beauty. Don’t conceal vice or pretend it doesn’t exist in oneself and in others. See the workings of narcissistic desire and overcome it. Learn about the games people play, the masks they wear and how erotic love enthralls and obsesses your heart. Become drunk not on profane love, but on something truer, purer and more everlasting. Ultimately, Blake tells us to closely observe the cunning workings of evil. Know the good by first cultivating a thorough knowledge of its opposite. Realize also that evil contains within itself the seeds of its own destruction. And crucially, what might from one perspective appear to be evil may actually serve a higher order – which no amount of mystique, deception and silence can compromise or destroy. |

|

Come Follow Us on Twitter – Come Like Us on Facebook

Check us out on Instagram – And Sign Up for our Newsletter