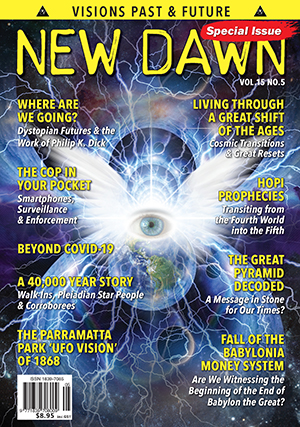

Where Are We Going?

Dystopian Futures & the Work of Philip K. Dick

Founded in the aftermath of the first nucleus-splitting explosions in the 1940s, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists is a panel of nuclear and other specialists. Every year, they estimate how close we are to Armageddon. They use a clock to analogise the dangers. In 1947, with the technology for global destruction, but not the means to deliver it, the time was “7 minutes to midnight.”

When in 1953 the Soviet Union exploded the hydrogen bomb, scientists at the politicised Bulletin moved the symbolic clock hands to 2 minutes to midnight. The creation of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) provided states with the means of carrying weapons that could destroy the world. Last year, the rabidly anti-Donald Trump Bulletin moved the clock hands to the closest they have ever been to midnight: 100 seconds. [Editor’s note: On 24 January 2023, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved its “Doomsday Clock” forward to just 90 seconds to midnight.]

Much more likely than nuclear war is nuclear accident: computer error, miscalculation, strategic escalation, etc.

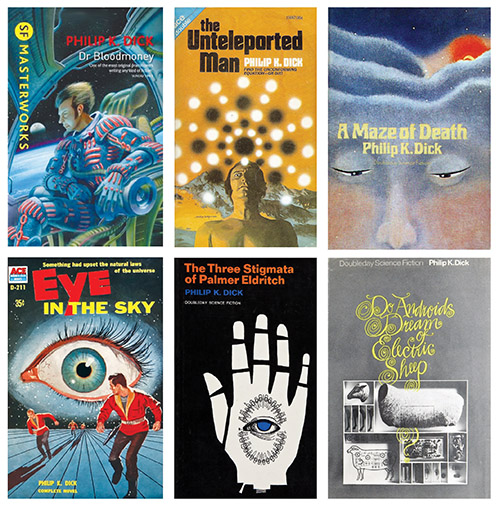

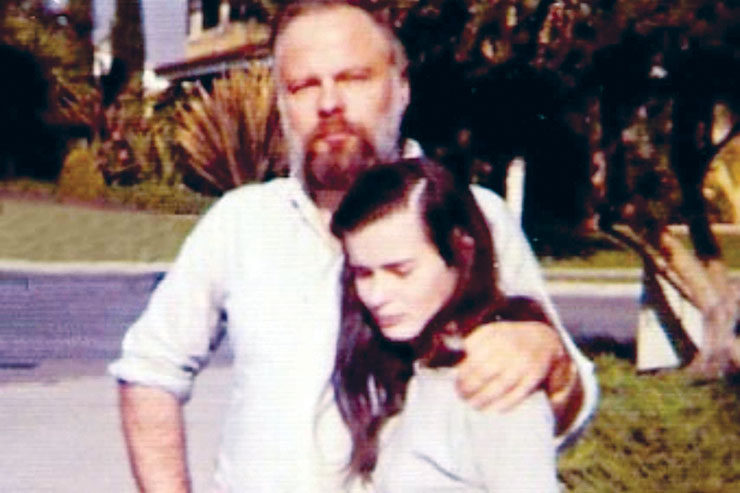

If we survive possession of nuclear weapons and, crucially, the means to deliver them, what kind of future can humans in Western societies expect over the next century? In nearly 200 stories, including shorts and novels, the late science-fiction novelist Philip K. Dick (1928–82) offered dozens of scenarios, some of which seem to be happening today.

In the novel Dr Bloodmoney (1965), the eponymous character accidentally destroys the world in an effort to counter Soviet and Chinese nukes. Survivors, like the limbless Hoppy Harrington, rely on augmentation technologies to function. In real-life since the 1960s, the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency has been using brain-machine interfaces to augment human capacities, such as wiring armless veterans to machines to enable them to control robotic limbs with their thoughts. This technology will be used to design next-generation killers that can operate in harsh environments, including irradiated zones and deep space.

SYNTHETIC REALITIES

What is “real”? For millennia, philosophers and theologians have grappled with this issue. In his novel Eye in the Sky (1957), Dick writes about a multiverse in which half a dozen people are trapped as projections of their subjective unconscious. The novel explores themes of solipsism and the limits of conscious knowledge, asking how much or little we know about ourselves. Similar themes were explored by the psychoanalyst Carl Jung, whose work has been compared to Dick’s explorations of human motivations. Both dealt with end-time themes and humanity’s (in)ability to adjust to civilisational changes.

Technology has augmented representation to the point where it is hard to distinguish that which is “real” from that which is modified or complete fiction. According to the UK Ministry of Defence, out to the year 2036: “simulation and representatives will have a significant and widespread impact on the future and will become an increasingly powerful tool to aid policy and decision-makers. It will also blur the line between illusion and reality” (emphases in original). Deepfakes pose national security challenges, as videos of leaders in compromising positions can be invented from whole cloth with 1s and 0s and targeted at naïve audiences to influence their opinions. Holographic projections could fool observers into thinking they’ve seen something tangible which actually consists of pure light. Such technologies can be marketed at pop concerts that “resurrect” dead singers, just as much as they can for military operations.

Some philosophers have abandoned the word “reality” when speaking in generalities because the denotation is subjective and vague. Yet, we all believe that we are present in a physical world and that we are conscious: if not, we’d stop eating and drinking because food and hunger, etc., would not be “real.” This, too, leads to more intellectual problems because physics suggests that what is “physical” is merely potential in quantum fields. Consciousness, too, is considered a “hard problem” by neuroscientists and psychologists because there is no scientific framework for investigating consciousness, just aspects of what we call consciousness.

In The Unteleported Man (1964, later Lies, Inc. 1966), Dick tells a tale of commercialised, physical teleportation to an Earth-like utopia, which turns out to be an advertising ploy to hook unhappy colonists. In “reality,” the US Defense Department recorded the teleportation of light particles over small distances in the mid-2000s. The results do not appear to have been widely reported, if at all. Today, Chinese scientists are unwittingly feeding the New Cold War propaganda machine in the West with their own, much better-publicised teleportation experiments. Using virtual reality (VR), like the Oculus corporation’s headset, Facebook’s Reality Labs is trying to create a “metaverse” of augmented reality in which users can be digitally teleported into another’s VR space.

With reality under question, some philosophers advocate giving up intellectual searches and favouring spiritual ones: to de-condition oneself from sensory experience and just “be.” But here we get back to the circular argument: what is “just being”? Dick suggests that such questions can never be answered because of the limits of the human mind and the structure of that which we call reality. In A Maze of Death (1970), Dick’s characters talk of being “prisoners of our own preconceptions and expectations.” Dick’s work was Gnostic: a broad term for those who believe that existence is a kind of veneer of a deeper, more fulfilling experience kept from us by invisible forces.

“Reality,” for Gnostics like Dick, is an artificial construct; a kind of con-trick at best and prison at worst, designed and sustained by powers that cannot ordinarily be detected or defeated. Dick’s novels concerned themselves with antiheroes who found themselves in situations in which the “real” them was indistinguishable from the fake them and real or fake others. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), for instance, adapted into the movie Blade Runner (1982), concerns human life in a society permeated with “replicants” who, for all intents and purposes, could be human. Although physically human-looking robots are a long way off, chatbots already trick humans into thinking they are real. The first successful bot was “Eugene Goostman,” which tricked a significant number of participants into believing it was a human. Untold numbers of troll bots post fake reviews on Amazon.

From this, we can ask: if “reality” is unreal in the sense of it being someone or something else’s construct and that there is some kind of “true reality,” how much of you is “real” and how much of you is the result of unchecked, unquestioned, and unchallenged conditioning? The conditioning can be from nature (limited consciousness, sensory conditioning), from other people (who tell you what to do and to believe from infancy), and your own internalised conditioning that perpetuates the tricks and lies.

Anthropologists and sociologists call personality a social construct. In other words, if you developed your mind and personality in a cultural vacuum – no religion, no politics – how different would you be? But without social inputs, including those of culture, the infant brain does not develop. So, we are back in the trap: you need input to develop but are you the sum of those inputs or do you have unique qualities? Is the uniqueness your true self?

THE POLITICS OF THE TRUE SELF

One perennial philosophy is: know yourself. But can the self be known in the contradictory circumstances in which we find ourselves? Corporations that seek to maximise profit and politicians who seek to control the public take advantage of our lack of self-knowledge. They use education, culture, propaganda, and fear to construct artificial personalities, turning us into a kind of “replicant.”

In the film The Adjustment Bureau (2011), based on Dick’s short story Adjustment Team (1954), non-human interventionists interfere in the life of an upcoming politician. At first, the audience thinks that these beings are political rivals, but (spoiler alert) they are nudging him away from his soul mate to pursue the higher goal of self-sacrifice for the greater social good.

In today’s online culture, you are the product. The World Wide Web spins its threads in which to trap the surfer. Instead of doing work for the greater good, the surfer is manipulated by myriad institutions and individuals to follow certain paths beneficial only to the manipulators. Brokers and ad agencies steal your data. We live in a performance, for-profit culture in which the self can be commodified in online spheres.

One of Dick’s famous quotes is: “There will come a time when it isn’t ‘They’re spying on me through my phone’ anymore. Eventually, it will be ‘My phone is spying on me’.” Today, the phone is life for millions of people. It allows us to access emails, the news, take photos, purchase goods and services, surf the net, check our health status, and even prove vaccination. Dependence on technology gives intelligence agencies and Big Data endless opportunities to control and manipulate. In Dick’s day, spy agencies would listen in through the phone, but today the technology inside the phone automatically passes data to the given agency.

Cell towers triangulate the user’s geolocations, even when the phone is switched off. The International Mobile Equipment Identity is a 15-digit number that identifies phones on a network. Phones also store user IP addresses. Apps can also spy on users. Angry Birds, CamScanner, DoorDash, Grindr, Ring Doorbell, Tinder, Weather apps, WhatsApp, and Zombie Mod, have all been found to be Trojan horses for the US National Security Agency and/or covertly passing user data to brokers. Caveni Digital Solutions founder Raffi Jafari says: “If you are looking for apps to delete to protect your information, the absolute worst culprit is Facebook,” as well as its WhatsApp, Messenger, and Instagram. “The sheer scale of their data collection is staggering, and it is often more intrusive than companies like Google.”

In the movie Minority Report (2002), based on Dick’s short story, society is saturated with advertising: from interactive ads on cereal packets to voice-to-skull technology that beams commercials into the heads of people passing by. Today, real-life adverts are targeted at the users, but data to refine targeted ads is sucked out of “personal” devices, creating a feedback loop. “[T]oday we live in a society in which spurious realities are manufactured by the media, by governments, by big corporations, by religious groups, political groups – and the electronic hardware exists by which to deliver these pseudo-worlds right into the heads of the reader, the viewer, the listener.” Dick said this in 1978. “I ask, in my writing, What is real? Because increasingly we are bombarded with pseudo-realities manufactured by very sophisticated people using very sophisticated electronic mechanisms. I do not distrust their motives; I distrust their power.”

Whatever is “real” about the human is being gathered and uploaded into myriad VR programmes that benefit our controllers but, crucially, make us superficially happy in the process so that we do not rebel, like the contented slave of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932). The military-industrial complex is trying to aestheticize the technologies of control to make them appealing to users. One designer worked with the RAND Corporation on the concept of “Internet of Bodies,” a biological step up the ladder of the “Internet of Things.” In this new age of bioconnectivity, Bluetooth-connected apps tell parents when their babies have shat. Artificial pancreases send real-time data on glucose levels to algorithms that automate insulin dosing. Wearable Attention Monitors use brain activity to track inattentiveness during scenarios like driving. Digital pills transmit biodata on reactions to ingested tablets.

In The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1965), Dick wrote about the blend of VR and genetic enhancement. In our real world, the “real” is being modified at the genetic level to create new physical biorealities: from engineered babies to enhanced food, from gene editing to mRNA vaccines. But who benefits? GMO food is sold to international consumers as a cure for global hunger, while domestic consumers are often not told that modified products are in their foods.

The human body has receptor cells (7 and 8) that shut down host cell protein synthesis, thereby preventing the use of certain materials as vaccine vectors. Modified messenger RNA enables the vector to escape detection, triggering the immune system to help the body fight similar infection: in theory. mRNA research developed into the 2010s, some of it with funding from the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. But the untested (on humans) technology had no chance of being mass-marketed until COVID came along. Pfizer, BioNTech, and Moderna developed mRNA vaccines accordingly.

Transcendence & Control

Dick also prophesied that “[c]omputer use by ordinary citizens… will transform the public from passive viewers of TV into mentally alert, highly trained information-processing experts.” But the price of mental alertness is addiction to screens. It is also losing our physical selves in a digital realm. The human is not merely a data processor; humans themselves become data that unseen powers buy, sell, manipulate, and use to create further synthetic realities. With so much online influence in the form of peer pressure, propaganda, targeted marketing, biosurveillance, and non-physical interaction, what it means to be human is challenged in the constant environment of Internet-of-Things. What it means to be physically human is also challenged as unaccountable corporations tinker with food, vaccines, and even the cells that produce humans. Dick’s characters, and indeed Dick himself, struggled to navigate this ever-shrinking minefield.

Perhaps more important than outer, modified constructs is the inner world inhabited by the characters. Our techno overlords have not yet mastered how the inner self projects reality externally and how the external world conditions the individual to internalise their control. The latter fascinated Gnostics like Dick, who felt the glimmer of transcendence in the darkness of matter and synthetic reality.

Dr Tim Coles