ART & IMAGINATION

The Western world in general does not realize that most of the major advances in science have come through imaginative thinking – Albert Linderman

Throughout my work I consider the difference between the Will to Power and Will to Meaning. I speak about the underlying drive of consciousness to regain a sense of lost wholeness, and how this quest has in recent decades ceased to be important to most people.

The state of affairs also entails dissociation, historical amnesia and disinterest in the warnings and lessons of the past. It leads to an obsession with religion, and, creatively, to the poisoning and degradation of Imagination.

Imagination, although accepted as important by artistic types, is usually considered something inessential and airy-fairy. It’s usually relegated to a position below logic, intellect and rationality.

However, like William Blake before her, Ayn Rand emphasized that imagination undergirds reason, which cannot function correctly without it.

In her important book The Romantic Manifesto, Rand explores the dynamic between Self and World, and analyzes the reasons for art and creativity. Her insights are exceptionally instructive for those wishing to understand consciousness and the purpose of human beings.

Art does have a purpose and does serve a human need, only it is not a material need, but a need of man’s consciousness. Art is inextricably tied to man’s survival – not to his physical survival, but to that on which his physical survival depends: to the preservation and survival of his consciousness – Ayn Rand (The Romantic Manifesto)

Ayn Rand’s masterly book analyzes the deep connections between consciousness and nature or Self and World

In her book and larger corpus, Rand emphasizes that consciousness does what it does and is what it is because of orderliness and context. A consciousness in chaos, with clashing thoughts and emotions, has no solid, sane grasp of reality, and never will. Many are those who fall into this category. Indeed, we understand neurosis and madness in contrast to their opposites. In terms of pathology, we know the “abnormal” because we encounter and favor the normal.

Of course, according to Rand and other thinkers, the “normal” – the sane, sensitive, rational, independent and heroic – is under attack from all sides. Rand addresses why this is and what can be done about it.

The structure, orderliness and independence of mind comes about when there is a healthy flow between Perception and Conception, two of the main functions of consciousness. The flow is not in a single direction. It also runs backwards from Conception to Perception. In fact, without this latter flow there would be no art in our world. We’d know nothing of painting, poetry, music, architecture or craftsmanship.

True art, explains Rand, is the result of mental orderliness. Bad art signals the opposite, arising due to a breakdown in mental orderliness or some other malignancy compromising the natural flow from Perception to Conception and back again.

By organizing his perceptual material into concepts, and his concepts into wider and still wider concepts, man is able to grasp and retain, to identify and integrate an unlimited amount of knowledge, a knowledge extending beyond the immediate concretes of any given immediate moment – Ayn Rand

By way of perception we introject objects and entities encountered in the world. Their images stand before us, to become part of us by way of our acts of perception. We know these as “ideas,” although we rarely consider how and why they exist.

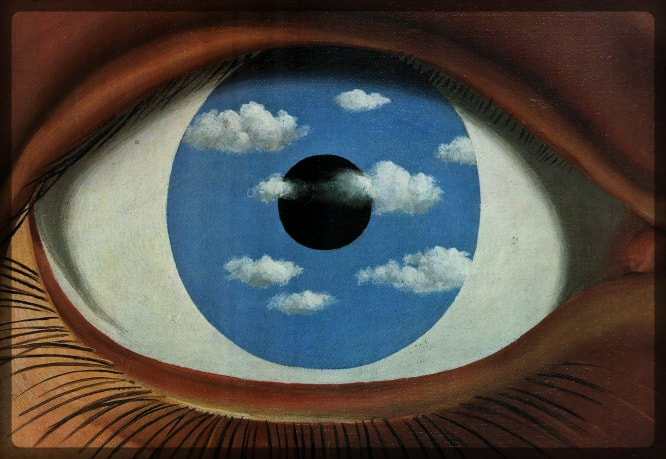

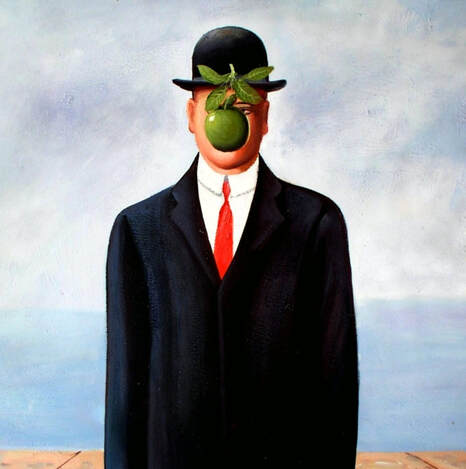

Perception was of utmost importance to certain philosophers, such as George Berkeley and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and to ingenious artists such as Salvador Dali, Rene Magritte, Henri Rousseau and Georges de Chirico, who not only painted and recorded what they saw, but also frequently incorporated comment on the act of seeing.

Artists of this caliber knew that perception is far from passive. The images of everything we look at are taken into the mind to become part of us. Moreover, these images are changed by perception. They become malleable and sometimes radically different from what they were before encountering a mind. Indeed, as certain philosophers warned, the world’s objects and entities – indeed the world itself – can’t be seen as they really are due to our mind’s ability to not only see reality but to transform it.

In other words what we see is what we see, not what is really there in the world. This implies that an inherent ambiguity exists because of our acts of perception. Our gaze reveals and also conceals what we wish to see. It separates inner and outer worlds, images and substance, subject and object. This has enormous consequences for our personal connection with reality and relationship with Self and World.

The striking fact is that what we encounter and experience isn’t a world but an image. As the German philosopher Immanuel Kant first demonstrated, we are only ever in contact with images, never things in themselves. Additionally, images, being ambivalent, reveal and also conceal what we deign to call “reality.”

What is rarely if ever noticed is that our acts of perception implicitly include acknowledgement of mystery. What seems to be a simple, direct act is anything but. Materialists construe sensual awareness as immediate and uncomplicated, something guaranteeing a concrete material world. Nothing could be more flagrantly absurd and false. What the materialist doesn’t face, is that mystery exists permanently and irrevocably because of our very own senses. To exist is to be enveloped by mystery whether one likes it or not. Artists like William Blake keep this fact very near to their hearts.

Considering the reciprocal relationship between Self and World, it is as if the stuff of the world also leans toward us, yielding to our gaze and mental capacities. Despite the concealed essence and ambivalence of objects, paradoxically they do not resist being altered by mind. Indeed, they become something more than what they once were after undergoing transmutation from perception to conception.

This movement and transmutation is fundamentally important to true Artists, giving rise to what we know as creativity.

When we observe the world, we encounter not only external objects and entities, but the Self perceiving them; a Self which can observe itself. In this sense, perception nucleates duality, bringing the external within, and making the material mental or ideal. English artist, William Blake, believed that this intaking or absorption of the world is made possible by Imagination, without which other mental capacities are relatively blind and ineffectual.

Intellectus in Latin means “perception” – Nicholas Hagger

Perception is the means by which the apparently external “material” world becomes psychic or mental, which means that its externality is nullified to a degree. Perhaps this is why sages like Blake, Berkeley and Merleau-Ponty so highly rated the mysteries of perception. For them our acts of seeing are quite magical.

The eye symbol turns up in prehistoric art, especially in ancient Egypt, where the so-called Eye of Horus had a life of its own, going about having all sorts of experiences. Perhaps the Egyptians were simply trying to figuratively describe the experience of everyone’s eyes that reach out to encounter a world and uncover its meaning. In this sense the eye is the instrument of psychic intentionality, our innate inclination toward reality.

Perhaps the Egyptian artists wanted to stress that the human eye is an object in the world, as are the things it observes. An eye is detached but also in amongst the world of things it beholds. It is at the same time superior to and equal to worldly phenomena.

The human eye is a portal or gateway where Self and World meet. High art is chiefly a discourse on this encounter.

So in one sense reality leans toward us, yielding to our gaze and Will to Meaning. This is why Rand explicitly deals with the differences between low and high art. Her point is that the world has no inherent meaning or value beyond what a mind attributes to it. Weak, lazy, uninspired types project no meaning upon the world, preferring to live as uncreative consumer-types utterly disinterested in the numinous encounter between Self and World and all it implies. If creativity appears at all, it’s usually that of other people, there to merely decorate one’s inauthentic and largely vacuous life.

Laziness factors in for Rand at the level of conception. In the dynamic, perception is relatively passive. But at the stage when a mind processes and arranges the world’s incoming content, libido is definitely involved. The lazy, indifferent mind is disinclined to organize or structure sense data, or to assign meaning to it. Whatever significance is assigned to things and thoughts is that of a mundane nature. It’s merely pragmatic and utilitarian.

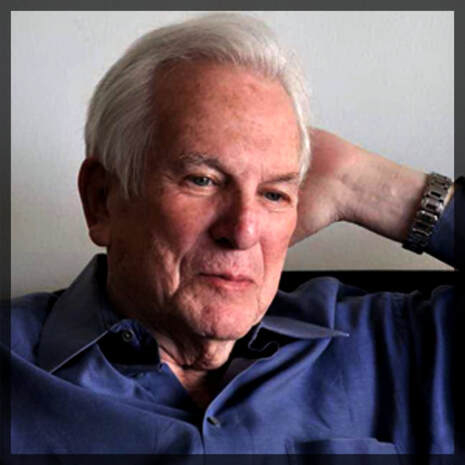

Nathaniel Branden was an American psychologist and philosopher. As Ayn Rand’s closest colleague, his many fine books extrapolate on her ideas, particularly on the connections between perception, conception, reason and values.

Rand’s successor, Nathaniel Branden, continued to unpack her ideas on the anatomy of consciousness. He too emphasizes how lazy, uncreative types fail to assign value to their lives, experiences and concepts. In effect, their concepts stand like a flimsy house of cards. Refusing to waste energy organizing sense data, they are incapable of awakening meaning from within.

Their unstructured, shrunken concepts and ideas in turn disaffect perception, thereby causing epistemological impoverishment. Branden states that for this type, self-concept and world-concept are emaciated and irrational. Instead of being infused with meaning, purpose and value, the lazy mind is satisfied to remain passive, chaotic and uncreative. Such a type’s psycho-epistemology is malignant and deranged. Indeed, their thinking works to contradict and cancel itself, because if one does not value themselves – and the life they’ve been given – they can hardly value anything or anyone else, except on a primitive superficial level.

Very often this type, in order to compensate for their existential malaise, turns to religion, hoping to camouflage their greyness behind a facade of intelligence and purpose.

According to Rand and Branden, such a type lacks true individuality and independence. Consequently they are bound to value the voice of the masses and depend upon the will of the necrophilous Crowd. Any direction or inspiration received and felt comes from external sources. Meaning is never generated from within.

What does the lack of individuality mean for one’s perception of reality? Can reality even be perceived through the haze of the Many?

What Branden refers to by the term “psycho-epistemology” is our ability to value our minds and ability to think. Every human being has the capacity to think, but not everyone puts in the work to think sanely, efficiently and reverently. Far from it.

For Rand the main problems are our negation of reality and penchant for reality-distortion, the latter being endorsed by the Collective. She highlights our inability to attend to nature and attune our minds to it correctly, a problem made more difficult by our incarceration in sterile urban environments. In fact, some thinkers believe we purposely build towns and cities in order to perpetuate mental docility. We shut nature out with our plate glass, concrete and steel, because to encounter nature demands mental and physical energy. It demands we attend to nature and ignore the Collective. It demands we sensitively come up against the numinous mysteries of nature, which in turn opens up new levels of Self-understanding. This is because any and every encounter with nature (Umwelt) is simultaneously an encounter with Self, and vice versa. One is the mirror of the other.

Rand’s Artist finds the energy to attune himself with nature. He is never wholly unaware of his awareness, becoming an artist to enhance his dialogue with nature, that he might benefit from nature’s subtle instruction.

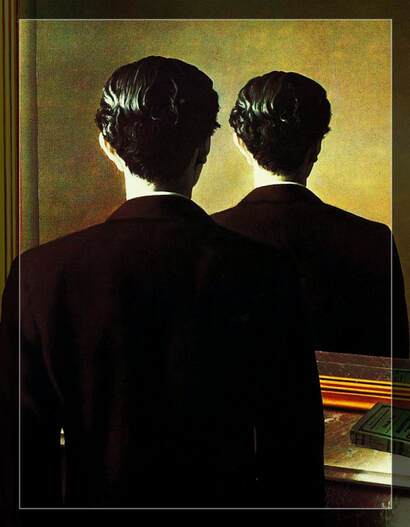

High art exists as the means by which concepts reemerge in the world as ideas and percepts to be re-contemplated by mind. Rather than remaining as concepts in one’s head, they appear before us to be reviewed, revisioned and reabsorbed. In this sense the conceptual mind is self-reflexive. According to Rand, this process is the necessary foundation of healthy societies and explains why we experience two worlds: the inner and outer. Neither is illusory. They exist as epiphenomena of the flow of images between outer and inner worlds.

The man who values his capacity to think and reason attends to the world of nature, fully aware of the dire consequences for not doing so. He knows that to avoid doing so lowers the quality of his life. It’s a sacrifice he’s not willing to make just to win society’s approval or a fleeting sense of security.

For Rand and Branden the artist is any person who wishes on some level to explicitly celebrate their attunement with nature and enhanced awareness of reality. Their creative ideas and productions display sophisticated thinking, feeling, understanding and wonder, thereby inspiring and directing onlookers and admirers. This is why great art captivates us, encapsulating and narrating the vast process by which perceptions become conceptions. This is why it awakens a sense of wonder and deep feeling.

Creativity is the power to connect the seemingly unconnected

– William Plomer

The Self is the Artist, and the Artist is the Self.

The two terms are synonymous.

We normally enjoy art because it embodies and expresses our underlying understanding of intentionality or natural inclination toward reality. We enjoy gazing at great paintings not only for what they objectively contain, but for what they perpetually bring forth from within us. By way of art we learn about ourselves. We also learn that Self-discovery is a process without end.

The deeper we delve into the mysteries of material nature, the more we become aware of the inadequacy of objective, physical principles and processes to explain the organic unity of individual consciousness and human experience – Gary Jacobs (Intelligence of the Cosmos)

This is what makes art and artistry fascinating. Again, we’re talking about the mysteries of perception and the basal metaphysical Template of Wholeness by which context and meaning are generated.

The mental organization of sense data (or images) is a complex and vast process. It is the process by which we get a world in our head, so to speak. Because it occurs naturally, we give it little attention. However, at times during the omnidirectional process, conceptions are disgorged, as it were, becoming the ideas appearing in our artwork. It is as if we return to the world that which we took from it in the form of perceptions. In this sense it cannot be denied that mind effects matter to a great extent. The world around us is shaped by human concepts which, in the form of ideas, return from whence they came, changing the world we see. Nothing remains static, not the person, not his world.

As far as Merleau-Ponty was concerned, this reciprocal exchange between Self and World is to be understood as an empathic relationship, similar to that existing between individuals. We not only lean toward world by way of innate intentionality, but we bring world within our being, giving it dimensions it perhaps does not possess in itself.

He understood that for all we take from the world by way of voracious perceptions, we give back in the form of rich conceptions. Indeed, after all is said and done, might it not be the cosmos that thinks and imagines through us? As Nietzsche questioned, do we really control our thoughts and know where they come from?

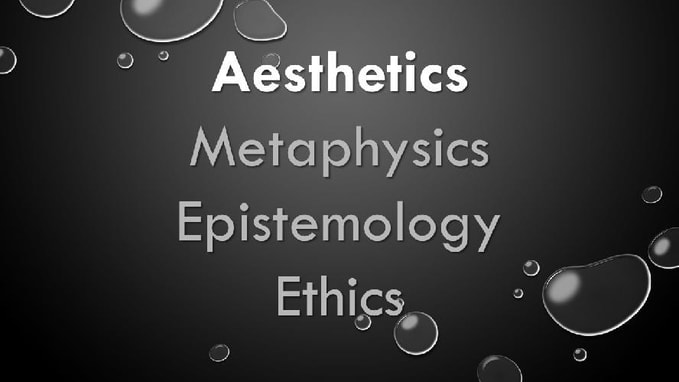

Since we are speaking primarily of images and their interaction, it follows that we must position the philosophy of Aesthetics above Metaphysics, Epistemology, Ethics and Politics. Rand’s Romantic Manifesto stands as an excellent guide for this radical reconstitution of philosophical paradigms. She succinctly argues that high art is nothing less than the sign of a person’s sanity, demonstrating their vivid acknowledgement of the world around them, as transformed by conception (or Imagination).

The eye and other senses are the physical means by which we express intentionality and Will to Meaning. However, once our psychic exchange shrinks and ceases, we end up inhabiting an ugly sterile world suitable only for creative mediocrities.

To reduce man’s consciousness to the level of sensations, with no capacity to integrate them, is the intention behind the reducing of language to grunts, of literature to “moods,” of painting to smears, of sculpture to slabs, of music to noise – Ayn Rand

.

The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way. Some see in nature all ridicule and deformity…and some scarce see nature at all. But to the eyes of the man of imagination, nature is imagination itself – William Blake

Although she does not refer to him, I believe William Blake would have agreed with Ayn Rand’s philosophy on many points. Instead of speaking about “conception,” he preferred the word “Imagination.” Essentially, however, he meant the process spoken about here, by which perception becomes conception and vice versa.

He also included the undergirding Template of Wholeness without which no order can be imposed on or by mind. This underlying template is not consciously or wilfully foisted on sense data. It’s an innate category existing far below conscious awareness. For Blake, it is as if external sensual objects have a intrinsic relationship with this mental template.

As stated earlier, worldly objects do not physically enter our heads. Rather, their images are introjected. Hence Blake’s exaltation of Imagination. Whatever a mind does to these images is therefore undeniably an Aesthetic act. And for a mind to influence and transform an image means that mind itself is imagistic. This was axiomatic for Blake, Rilke, Magritte, Marcel, Croce, Gibran and other thinkers who knew that when we say idea we really mean image.

Whatever structure is imposed by mind upon an image isn’t necessarily foreign and antithetical to it. For Blake, mind enhances the perceived identity of objects. Identity is, in this sense, revealed. More of an object’s inherent nature is brought into the light, its normally hidden dimensions exposed. It is as if the object finds fuller expression when – by way of a great artist – it is brought into the proximity of the Template of Wholeness.

Blake’s philosophy, in this regard, is close to that of Gabriel Marcel, Benedetto Croce, Merleau-Ponty and Martin Heidegger, each of whom considered art to be of a higher order than philosophy.

When concepts reappear in the world as high art, man gains invaluable insight into his core nature. He gets to see the lineaments of his consciousness, both the positive and negatives. He sees that he is indeed a seeker, and that he innately strives to upgrade his understanding of Self and World. He acknowledges the task before him, and summoning will and Self-esteem he heroically commits to the great journey toward greater revelation and Self-realization. In this way, heroism, Self-esteem and art are deeply connected, the latter serving as a mirror in which man espies his heroic identity. Art is the means by which we extend beyond limits, and by which we return to ourselves again to assess our progress or regress. It is how we realize the two ways of seeing, the inner (conception) and outer (perception), and attend to the dynamic relationship between them. Ultimately, the Artist is one who upgrades his Aesthetic Sensibility and sense of the Sublime. Throughout my work I stress the importance of upgrading Aesthetic Intelligence by which our being becomes increasingly transparent to us. (Here for more…)

Heidegger was careful to distinguish Aesthetics from artistry that is little more than mere decoration. To understand why Aesthetics must supersede other philosophical paradigms is to radically revision human consciousness along non-materialistic lines. Our conventional notions of identity, perception, vision and perspective must undergo transmutation. It’s an impossible task, however, unless one becomes an Artist to thereby work closely with images and be instructed and led by them.

In a similar sense as Rand, Blake explains that we get up close to the world not by intellect or reason alone but by Imagination. He used this word to include our natural tendency for intentionality, our reaching toward the world and its yielding to our gaze.

There was no doubt in Blake’s mind that what is experienced of a world is determined by ideas or images. Unlike conventional Rationalists he did not acknowledge that mind is separate from the world. He knew that what we know of “the world” is based on its image in our heads. It can never be any other way.

This is not to say that the world has no inherent substance and meaning. However, whatever meaning we find in the world is ultimately a matter of inference, and the world giving back what we mentally extend to it. In this regard Blake is consistent with Rand who stressed that without a healthy psycho-epistemology there can only be chaos and vacuity.

Each and every moment, our experience of the world is made possible by the activity of Imagination, which not only attributes meaning to our experience of persons and things, but personalizes their influence upon us. What we experience is always our experience. Otherwise one person’s experience would be a matter of dry mechanical mental processes. One’s reality, and image/idea of the world, would be practically identical to another’s, and freedom would cease being the essential nucleus of consciousness.

Each person’s experience of the world is different from others because beneath the Template of Wholeness lies freedom. Without freedom at the base of consciousness, identity and being, man would not be able to produce artwork of any significance. This is because a person’s creations express something about their core nature. Art without uniqueness has little to no meaning, being merely functionally decorative. As stated earlier, art exists as the means by which we express in images who we are as Selves, and also as the means by which we continually experience new revelations about Self and World. Ideally, the process is without end.

For Blake, Imagination matters because it not only draws forth the hidden essences of things, but also of the Self. After all, our experience of any other thing impacts the Self as experiencer. In each and every encounter with the external world we inevitably experience an act of Self-positing, albeit in the background of awareness. In any case, as Selves we are always involved in every thought, deed and relationship. Where the other is, so the Self must also be. It’s astonishing how little contemplation this fact receives from millions of truly selfless people.

Blake’s Imagination is therefore identical with the Template of Wholeness by which images of things and Selves blend, commune, self-reveal, morph and sublate. The process of revelation is highly enigmatic, however, since what is also revealed to a Self is Self’s eternal mysteriousness.

After all, what we refer to as Self is really an image and matter of art. Moreover, our image of Self is not static. It changes constantly as it encounters the world of which it is a part. Suggestively, the physical body also stands like any other object in time and space, like a table, tree or mountain. However, there is no denying that essentially it too is an image introjected by way of perception, enveloped and transmuted by way of conception. Crucially, we see that the perceiving Self transcends the subject-object polarity, being at the same time both perceiver and perceived.

Conception is inner seeing, without which there can be neither Self nor meaning. Who is the Hidden Observer behind the Self?

The whole business of man is Art and all things common – William Blake

In different ways Blake and Heidegger emphasize that when it comes to the Self there are definite limits to knowledge. Paradoxically, we know about the Self by way of the Self. But the Self’s extent cannot be wholly circumscribed, even by itself. What we know of Self always stands alongside what we do not and cannot know about it. Simply put, Self is a mystery to Self, and as Blake knew all too well, Imagination is the primary means by which a Self seeks to unveil the mystery of itself. All other mental capacities – intellect, logic, reason, intuition, memory, emotion, etc – being servants in Imagination’s cause, with little value in and of themselves.

In other words, as far as Blake, Rilke, Marcel, Merleau-Ponty and Heidegger were concerned, perception and conception (or Imagination) are instrumental to our encounter with mystery, as it pertains to Self and World. Indeed, without this abyssal aspect of the Self, we’d not be inclined to press up against the world or lean out toward reality, given that in doing so we develop Self-knowledge. Likewise, every concept is bound to include the presence and influence of the world. This empathic relationship and reciprocal exchange – along with process, progress, Self-esteem and mystery – is therefore an absolute when it comes to the Self and its enigmatic relationship with itself.

Consequently, our Being in the World is to be understood as a means to this end, the ongoing encounter with Self and its eternal mystery.

. . .

Michael Tsarion