Our Revolting Elites

The ‘revolt of the elites’ has reversed the source of social disorder from the masses to the elites.

Prescient social critic Christopher Lasch’s 1996 book, The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy, laid out a blueprint of social decay that continues to inform our descent into social disorder. Lasch excoriated our revolting elites for abandoning the foundations of social stability, upward mobility, the middle class and democracy in their race to enrich and insulate themselves in protected enclaves–neighborhoods, corporate suites, foundations and institutions–of fellow elites.

In Lasch’s analysis, America’s elites are revolting against the obligations imposed on traditional elites to nurture the foundational values that support democracy, national purpose, civic pride and a moral order that restrains narcissism and greed as a means of protecting opportunities for advancement from the pillage of the wealthy.

Lasch identified the ways in which globalization fosters elite pathologies. In his view, America’s technocratic elites are a new class of symbolic analysts whose financial means “rest not so much on the ownership of property as on the manipulation of information and professional expertise.”

Serving trans-national corporations, foundations and agencies, they have “more in common with their counterparts in Brussels or Hong Kong than with the masses of Americans not yet plugged into the network of global communications.”

America’s elite defines itself as the hard-working winners of a Darwinian global meritocracy, an atomized world ruled by The Triumph of the Individual: “the new class has to maintain the fiction that its power rests on intelligence alone. Hence it has little sense of ancestral gratitude or an obligation to live up to responsibilities inherited from the past. It thinks of itself as a self-made elite owing its privileges exclusively to its own efforts.”

From this lofty perch, America’s elite is disconnected from those still mired in the real-world economy they’ve left behind: in Lasch’s words, the elite “betray the venomous hatred that lies not far beneath the smiling face of upper-middle-class benevolence… Simultaneously arrogant and insecure, the new elites, the professional classes in particular, regard the masses with mingled scorn and apprehension.”

In Lasch’s view, this revolt of the elites has reversed the source of social disorder from the masses to the elite: “Once it was the ‘revolt of masses’ that was held to threaten social order and the civilizing traditions of Western culture…Today it is the elites–those who control the international flow of money and information, preside over philanthropic foundations and institutions of higher learning, manage the instruments of cultural production and thus set the terms of public debate–that have lost faith in the values” that underpin a fair and vibrant social and economic order.

Lasch’s critique aligns with historian Peter Turchin’s analysis on the structural sources of social disorder which he has updated in his latest work, End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration.

This Salon article summarizes many of the conclusions in Turchin’s new book: Hope in “End Times”: Peter Turchin’s analysis of our coming collapse could help us avoid it:

For all its breadth and depth, there’s a simple message at the core of “End Times”: At the heart of our problems, Turchin writes, is “a perverse ‘wealth pump’ … taking from the poor and giving to the rich,” and we have to find a way to turn it off. America has essentially done that before, during the New Deal era, and other nations and societies have done it as well. But only about one in five of the nation-states or empires that face cyclical crises like the one we’re in today escapes it, Turchin reports. So the odds aren’t great, unless we act fast and with purpose, making full use of what we now know.

Turchin’s book strongly argues that something akin to New Deal reforms isn’t just a good idea in moral or political terms but is an objective necessity to avoid disaster and rebuild social trust. But he’s also clear about the deeply rooted forces that stand in the way of such reforms, casting them as damaging partisan politics or even an existential threat.

He sees four main drivers that lead to societal crisis, of which the most important is “intraelite competition and conflict,” and the most variable is “geopolitical factors,” which for large and powerful nations like the U.S. tend to be negligible. Another driver, “popular immiseration,” increases as population growth drives down living standards, which leads to “elite overproduction,” for example when too many middle-class college graduates compete for a stagnant number of well-paying jobs. The last driver, the “failing fiscal health and weakened legitimacy of the state,” is exacerbated by both popular immiseration and elite overproduction, which are clearly the central features.

Turchin also focuses attention on what he calls the “engine” at the heart of the model, the previously mentioned “perverse ‘wealth pump’… taking from the poor and giving to the rich.” It intensifies and locks in popular immiseration and also drives elite overproduction, undermining social trust at both the top and bottom of the social pyramid.

This reflects “one of the most fundamental principles in sociology, the ‘iron law of oligarchy,'” he writes, “which states that when an interest group acquires a lot of power, it inevitably starts using that power in self-interested ways.” For example, while wages fell far behind the growth of economic productivity from 1979 onward, Turchin cites analysis from the Economic Policy Institute indicating that three-fourths of that gap was due to elite-driven policy shifts: weakened labor standards, the erosion of collective bargaining, corporate globalization and so-called fiscal austerity.

Diminished economic conditions for the less educated were accompanied by a decline in the social institutions that nurtured their social life and cooperation. These institutions include the family, the church, the labor union, the public schools and their parent-teacher associations, and various voluntary neighborhood associations.

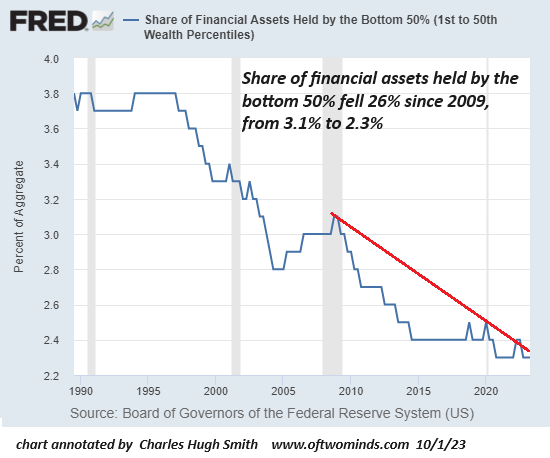

As evidence that Turchin’s “perverse wealth pump” has been running full speed, please glance at this chart showing the bottom 50%’s meager share of the nation’s stupendous financial assets fell 26% from 3.1% to 2.3% since 2009–a sliver so thin that it’s essentially signal noise.

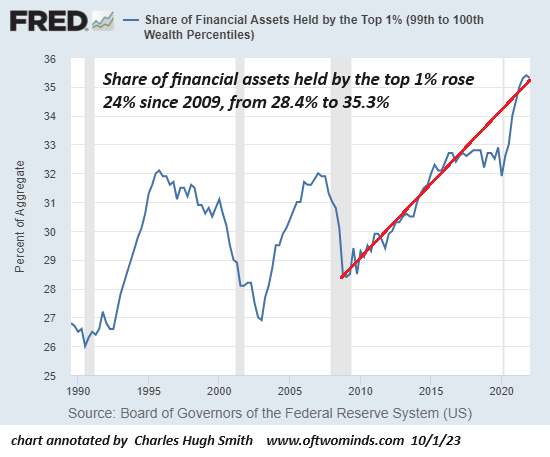

In contrast, the top 1%’s share of financial assets rose 24% since 2009.

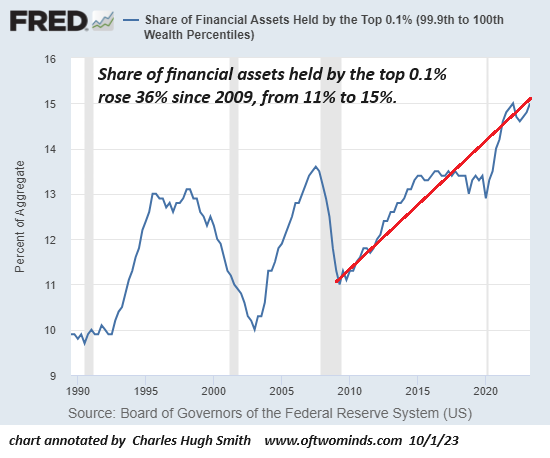

The top 0.1%’s share of financial assets soared 34%% since 2009.

In sum: our elites are revolting, and their narcissism, greed, moral decay and pathology must be restrained lest these forces dissolve our social order.