The Art of Nothing

by Thomas J. Elpel

Westerners who first met Shoshone bands of Indians in the Great Basin Desert described them as being “wretched and lazy.” Observers remarked that they lived in a wasteland, yet seemed to do nothing to improve their situation. They built no houses or villages; they had few tools or possessions, almost no art, and they stored little food. It seemed that all they did was sit around and do nothing.

The Shoshone were true hunter-gatherers. They spent their lives walking from one food source to another. Houses were useless to their nomadic lifestyle. They carried everything they owned on their backs from place to place. Extraneous tools, possessions, or art would have been a burden to carry.

We often expect that primitive cultures like the Shoshone must have worked all the time to stay alive, but in actuality these were usually very leisured peoples. Anthropological studies consistently revealed that nomadic hunter-gatherer societies typically worked only two or three hours per day for their subsistence. Like deer or other wild creatures, hunter-gatherer peoples had nothing to do other than wander and eat.

We often expect that primitive cultures like the Shoshone must have worked all the time to stay alive, but in actuality these were usually very leisured peoples. Anthropological studies consistently revealed that nomadic hunter-gatherer societies typically worked only two or three hours per day for their subsistence. Like deer or other wild creatures, hunter-gatherer peoples had nothing to do other than wander and eat.

The Shoshone enjoyed abundant liesure time because they produced almost no material culture. They were not being lazy; they were just being economical. Sitting around doing nothing helped conserve precious calories of energy so they would not have to harvest so many calories each day to sustain themselves.

Many of us westerners are fascinated with simple cultures, and a few of us actively reproduce or recreate the primitive lifestyle. In our typical western zeal, however, we emphasize production. We work ambitiously to learn each primitive craft, and we create primitive clothing, tools, containers, art, and knick knacks. Hunter-gatherer cultures carried their possessions on their backs, but us modern primitives need a pickup truck to move camp!

Many of us westerners are fascinated with simple cultures, and a few of us actively reproduce or recreate the primitive lifestyle. In our typical western zeal, however, we emphasize production. We work ambitiously to learn each primitive craft, and we create primitive clothing, tools, containers, art, and knick knacks. Hunter-gatherer cultures carried their possessions on their backs, but us modern primitives need a pickup truck to move camp!

In our effort to recreate the primitive lifestyle we miss the mark completely–we make many primitive crafts, but fail to grasp the true nature of a primitive culture, which requires letting go to practice the art of doing nothing.

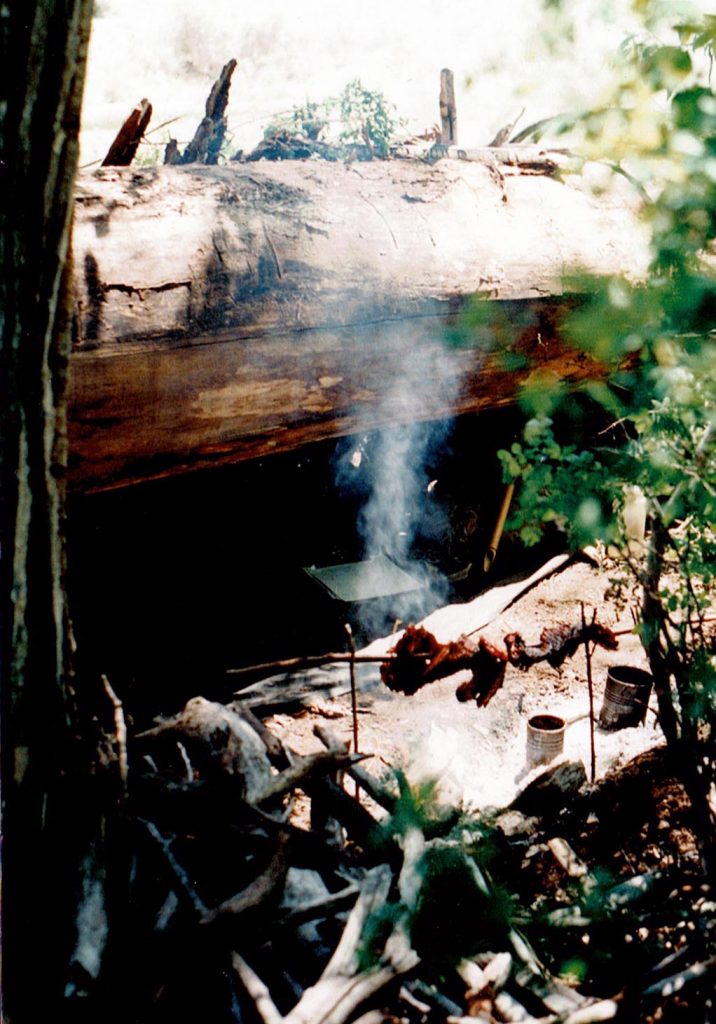

“Building a shelter from scratch can be very labor intensive.”

“Building a shelter from scratch can be very labor intensive.”

The art of nothing is a challenging concept for us westerners. Our culture idealizes productivity, as if the person who fells a tree is assumed to contribute more to the world than one who merely contemplates under its shady canopy.

When we go on a “primitive” camping trip, we take western preconceptions with us. We find a level spot in a meadow to build our shelter, and if the site is not level then we make it so. Then we gather materials and start from scratch, building the walls and roof of a shelter. We do what we are accustomed to; we build a frame house on a surveyed plot in the meadow. Then we gather materials and shingle our shelter, regardless of whether or not there is any chance of rain.

Those of us employed in the wilderness skills business perpetuate the western work ethic because it is easier to teach somethingrather than to teach nothing. It is easier to teach how to make something than to teach hownot to need to make anything. The do-something approach to primitive skills is to makeeverything you need, while the do-nothing method is to findeverything.

Those of us employed in the wilderness skills business perpetuate the western work ethic because it is easier to teach somethingrather than to teach nothing. It is easier to teach how to make something than to teach hownot to need to make anything. The do-something approach to primitive skills is to makeeverything you need, while the do-nothing method is to findeverything.

For example, the do-nothing method of shelter is to findshelter, rather than to build it. Two hours spent searching for a partial shelter that can be improved upon can easily save two hours of physically demanding onstruction work and typically result in a better shelter. Moreover, the do-nothing method of shelter is evalutate the incoming weather and to build only what is necessary. If fair weather is anticipated then you may be able to do-nothing to rainproof your shelter. Invest in a shelter that will keep you warm, instead of both warm and dry.

“The space under a fallen tree made a cozy shelter with only a few slabs of bark to close in the back.”

“The space under a fallen tree made a cozy shelter with only a few slabs of bark to close in the back.”

There are many acts, small and large, that a person can do, or not do, to better the art of doing nothing. This can be as simple as cupping one’s hands to drink from the stream rather than making and carrying a cup, or breaking sticks to find a sharpened point, instead of using a knife to methodically carve a digging stick. Hand carved wooden spoons and forks are do-something utensils to manufacture, carry, and clean. Chopsticks (twigs) are do-nothing utensils that can be quickly created on site and tossed in the fire after a meal.

Henry David Thoreau wrote of having a rock for a paperweight at his cabin by Walden pond. He threw it out when he discovered he had to dust it. That is the essence of a do-nothing attitude.

Through years of experimental research into primitive skills I’ve learned that there is rarely enough hours in a day to complete all of a day’s tasks. It is challenging to go out and build a shelter, make a working bowdrill set, set traps, dig roots, make bowls and spoons, and cook dinner. Hunter-gatherer societies succeeded in working only two to three hours per day, yet in our efforts to reproduce their lifestyle we end up working all day.

“The hole left by the uplifted roots of a fallen tree made a good shelter by leaning sticks and debris against the rootball.

“The hole left by the uplifted roots of a fallen tree made a good shelter by leaning sticks and debris against the rootball.

Practicing the art of nothing can save time and energy to finish daily work more effectively. Doing nothing becomes an approach to research; it is a way of thinking and doing. For instance, I’ve done many timed studies of various primitive skills, such as: How long does it take to construct a particular shelter? How much of a particular food resource can I harvest per hour? Can I increase the harvest using different gathering techniques? I observed that it is only marginally economical to manufacture common primitive deadfall traps. It is time intensive; adds weight to carry, and the traps often have short life spans. The do-nothing alternative is to use whatever is at hand, to pick up sticks and assemble them into a trap, without using even a knife. Preliminary tests of this “no-method” produced results equal to conventional carved and manufactured traps, but with a much smaller investment of time.

Primitive hunter-gatherer type cultures were very good at doing nothing. Exactly how well they did nothing is difficult to determine, however, because doing nothing leaves nothing behind for the archaeological record. Every time we find an artifact we have documentation of something they did; yet the most important aspect of their skills may have been what they did not, and there is no way to discover what that was by studying what they did.

Nevertheless, what you will discover as you learn the art of doing nothing is that you are much more at home in the wilderness. No longer will you be so dependent on tools and gadgets; no longer will you need to shape the elements of nature to fit our western definitions. You will find you need less and less, until one day you find you need nothing at all. Then you will have time on your hands to whatever you want, including possibly, nothing at all.

Thomas J. Elpel is the founder/director of Green University LLC in Pony, Montana and the author of numerous books and videos, including Participating in Nature: Wilderness Survival and Primitive Living Skills and The Art of Nothing Wilderness Survival Video Series available from www.hopspress.com.

Thomas J. Elpel is the founder/director of Green University LLC in Pony, Montana and the author of numerous books and videos, including Participating in Nature: Wilderness Survival and Primitive Living Skills and The Art of Nothing Wilderness Survival Video Series available from www.hopspress.com.

![]()

Primitive Living as Metaphor

Primitive living is a metaphor we participate in and act out. Life is simplified down to the bare essentials: physical and mental well-being, shelter, warmth, clothing, water, and food. We go on an expedition to meet those needs with little more than our bare hands.

In our quest we learn to observe, to think, to reach inside ourselves for new resources for dealing with challenging and unfamiliar situations. We build up our personal strengths, and at the same time we interact with and learn about the world around us.

In our quest we learn to observe, to think, to reach inside ourselves for new resources for dealing with challenging and unfamiliar situations. We build up our personal strengths, and at the same time we interact with and learn about the world around us.

In a story we can only join a quest in our imaginations. But in primitive living, we physically leave the contemporary world. We journey into the world of Stone Age skills, and we return with knowledge, wisdom, and strength to enrich our lives in contemporary society.

–Thomas J. Elpel, Author

Participating in Nature

Primitive Living Skills Get in touch with your wild side!

Home | Youth Programs | Adult Programs | Schools of North America | International | Gatherings

Articles | Journals | Books and Videos by Thomas J. Elpel | Links | E-Mail

![]()

Return to Thomas J. Elpel’s

Web World Portal | Web World Tunnel

Thomas J. Elpel’s Web World Pages

About Tom | Green University®, LLC

HOPS Press, LLC | Dirt Cheap Builder Books

Primitive Living Skills | Outdoor Wilderness Living School, LLC

Wildflowers & Weeds | Jefferson River Canoe Trail

Roadmap To Reality | What’s New?

© 1997 – 2019 Thomas J. Elpel

![]()

Top Image By PIXABAY

Come Follow Us on Twitter – Come Like Us on Facebook

Check us out on Instagram – And Sign Up for our Newsletter