The Death of the Festival

Part 1 of the Girard series

(Part 1 of a multi-part series, Part 2 here, Part 3 here , Part 3.5 here , Part 4 here )

We live a double life, civilized in scientific and technical matters, wild and primitive in the things of the soul. That we are no longer conscious of being primitive, makes our tamed kind of wildness all the more dangerous. – Hans Von Hentig

The natural order is unraveling. Plagues, floods, droughts, political unrest, riots, and economic crises strike one upon the next, before society has recovered from the last. Cracks spread in the shell of normality that encloses human life. Societies have faced such circumstances repeatedly throughout history, just as we face them today.

We would like to think we are responding more rationally and more effectively than our unscientific forebears; instead, we enact age-old social dramas and superstitions dressed in the garb of modern mythology. No wonder, because the most serious crisis we face is not new.

None of the problems facing humanity today are technically difficult to solve. Holistic farming methods could heal soil and water, sequester carbon, increase biodiversity, and actually increase yields to swiftly solve various ecological and humanitarian crises. Simply declaring a moratorium on fishing in half the world’s oceans would heal them too. Systemic use of natural and alternative healing modalities could vastly reduce Covid mortality, and reverse the (objectively more serious) plagues of autoimmunity, allergies, and addiction. New economic arrangements could easily eradicate poverty. However, what all of these easy solutions have in common is that they require agreement among human beings. There is almost no limit to what a unified, coherent society can achieve. That is why the overarching crisis of our time – more serious than ecological collapse, more serious than economic collapse, more serious than the pandemic – is the polarization and fragmentation of civil society. With coherency, anything is possible. Without it, nothing is.

The late philosopher Rene Girard believed that this has always been true: since prehistoric times, the greatest threat to society has been a breakdown in cohesion. Theologian S. Mark Heim elegantly lays outGirard’s thesis: “Particularly in its infancy, social life is a fragile shoot, fatally subject to plagues of rivalry and vengeance. In the absence of law or government, escalating cycles of retaliation are the original social disease. Without finding a way to treat it, human society can hardly begin.”

The historical remedy is not very inspiring. Heim continues:

The means to break this vicious cycle appear as if miraculously. At some point, when feud threatens to dissolve a community, spontaneous and irrational mob violence erupts against some distinctive person or minority in the group. They are accused of the worst crimes the group can imagine, crimes that by their very enormity might have caused the terrible plight the community now experiences. They are lynched.

The sad good in this bad thing is that it actually works. In the train of the murder, communities find that this sudden war of all against one has delivered them from the war of each against all. The sacrifice of one person as a scapegoat discharges the pending acts of retribution. It “clears the air.” The sudden peace confirms the desperate charges that the victim had been behind the crisis to begin with. If the scapegoat’s death is the solution, the scapegoat must have been the cause. The death has such reconciling effect, that it seems the victim must possess supernatural power. So the victim becomes a criminal, a god, or both, memorialized in myth.

The buildup of reciprocal violence and anarchy that precedes this resolution was described by Girard in his masterwork, Violence and the Sacred, as a “sacrificial crisis.” Divisions rend society, violence and vengeance escalate, people ignore the usual restraints and morals, and the social order dissolves into chaos. This culminates in a transition from reciprocal violence to unanimous violence: the mob selects a victim (or class of victims) for slaughter and in that act of universal agreement, restores social order.

The Age of Reason has not uprooted this deep pattern of redemptive violence. Reason but serves to rationalize it; industry takes it to industrial scale, and high technology threatens to lift it to new heights. As society has grown more complex, so too have the variations on the theme of redemptive violence. Yet the pattern can be broken. The first step to doing that is to see it for what it is.

In order that full-blown sacrificial crises need not repeat, an institution arose that is nearly universal across human societies: the festival. Girard draws extensively from ethnography, myth, and literature to make the case that festivals originated as ritual reenactments of the breakdown of order and its subsequent restoration through violent unanimity.

A true festival is not a tame affair. It is a suspension of normal rules, mores, structures, and social distinctions. Girard explains:

Such violations [of legal, social, and sexual norms] must be viewed in their broadest context: that of the overall elimination of differences. Family and social hierarchies are temporarily suppressed or inverted; children no longer respect their parents, servants their masters, vassals their lords. This motif is reflected in the esthetics of the holiday—the display of clashing colors, the parading of transvestite figures, the slapstick antics of piebald “fools.” For the duration of the festival unnatural acts and outrageous behavior are permitted, even encouraged.

As one might expect, this destruction of differences is often accompanied by violence and strife. Subordinates hurl insults at their superiors; various social factions exchange gibes and abuse. Disputes rage in the midst of disorder. In many instances the motif of rivalry makes its appearance in the guise of a contest, game, or sporting event that has assumed a quasi-ritualistic cast. Work is suspended, and the celebrants give themselves over to drunken revelry and the consumption of all the food amassed over the course of many months.

Festivals of this kind serve to cement social coherence and remind society of the catastrophe that lays in wait should that coherence falter. Faint vestiges of them remain today, for example in football hooliganism, street carnivals, music festivals, and the Halloween phrase “trick or treat.” The “trick” is a relic of the temporary upending of the established social order. Druidic scholar Philip Carr-Gomm describesSamhuinn, the Celtic precursor to Halloween, like this:

Samhuinn, from 31 October to 2 November was a time of no-time. Celtic society, like all early societies, was highly structured and organised, everyone knew their place. But to allow that order to be psychologically comfortable, the Celts knew that there had to be a time when order and structure were abolished, when chaos could reign. And Samhuinn was such a time. Time was abolished for the three days of this festival and people did crazy things, men dressed as women and women as men. Farmers’ gates were unhinged and left in ditches, peoples’ horses were moved to different fields…

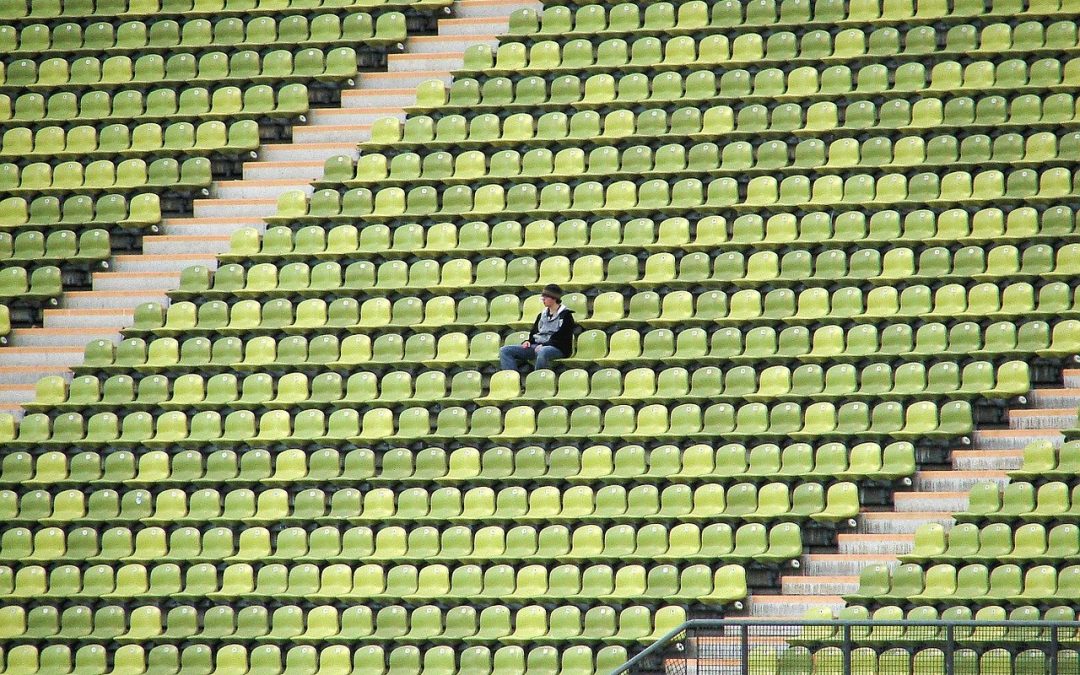

In modern, “developed” societies today, neither Halloween nor any other holiday or culturally sanctioned event permits this level of anarchy. Our holidays have been fully tamed. This does not bode well. Girard writes:

The joyous, peaceful facade of the deritualized festival, stripped of any reference to a surrogate victim and its unifying powers, rests on the framework of a sacrificial crisis attended by reciprocal violence. That is why genuine artists can still sense that tragedy lurks somewhere behind the bland festivals, the tawdry utopianism of the “leisure society.” The more trivial, vulgar, and banal holidays become, the more acutely one senses the approach of something uncanny and terrifying.

That last sentence strikes a chord of foreboding. For decades I’ve looked at the degenerating festivals of my culture with an alarm I couldn’t quite place. As All Hallows Eve devolved into a minutely supervised children’s game from 6 to 8pm, as the Rites of Resurrection devolved into the Easter Bunny and jellybeans, and Yule into an orgy of consumption, I perceived that we were stifling ourselves in a box of mundanity, a totalizing domesticity that strove to maintain a narrowing order by shutting out wildness completely. The result, I thought, could only be an explosion.

It is not just that festivals are necessary to blow off steam. They are necessary to remind us of the artificiality and frailty of the human ordering of the world, lest we go insane within it.

Mass insanity comes from the denial of what everyone knows is true. Every human being knows, if only unconsciously, that we are not the roles and personae we occupy in the cultural drama of life. We know the rules of society are arbitrary, set up so that the show can be played out to its conclusion. It is not insane to enter this show, to strut and fret one’s hour upon the stage. Like an actor in a movie, we can devotedly play our roles in life. But when the actor forgets he is acting and loses himself so fully in his role that he cannot get out of it, mistaking the movie for reality, that’s psychosis. Without respite from the conventions of the social order and without respite from our roles within it, we go crazy as well.

We should not be surprised that Western societies are showing signs of mass psychosis. The vestigial festivals that remain today – the aforementioned holidays, along with cruise ships and parties and bars – are contained within the spectacle and do not stand outside it. As for Burning Man and the transformational music & art festivals, these have exercised some of the festival’s authentic function – until recently, when their exile to online platforms stripped them of any transcendental possibility. Much as the organizers are doing their best to keep the idea of the festival alive, online festivals risk becoming just another show for consumption. One clicks into them, sits back, and watches. In-person festivals are different. They start with a journey, then one must undergo an ordeal (waiting in line for hours). Finally you get to the entrance temple (the registration booth), where a small divination ritual (checking the list) is performed to determine your fitness to attend (by having made the appropriate sacrifice – a payment – beforehand). Thereupon, the priest or priestess in the booth confers upon the celebrant a special talisman to wear around the wrist at all times. After all this, the subconscious mind understands one has entered a separate realm, where indeed, to a degree at least, normal distinctions, relations, and rules do not apply. Online events of any kind rest safely in the home. Whatever the content, the body recognizes it as a show.

More generally, locked in, locked down, and locked out, the population’s confinement within the highly controlled environment of the internet is driving them crazy. By “controlled” I do not here refer to censorship, but rather to the physical experience of being seated watching depictions of the real, absent any tactile or kinetic dimension. On line, there is no such thing as a risk. OK, sure, someone can hurt your feelings, ruin your reputation, or steal your credit card number, but all these operate within the cultural drama. They are not of the same order as crossing a stream on slippery rocks, or walking in the heat, or hammering in a nail. Because conventional reality is artificial, the human being needs regular connection to a reality that is non-conventional in order to remain sane. That hunger for unprogrammed, wild, real experiences – real food for the soul – intensifies beneath the modern diet of canned holidays, online adventures, classroom exercises, safe leisure activities, and consumer choices.

Absent authentic festivals, the pent-up need erupts in spontaneous quasi-festivals that follow the Girardian pattern. One name for such a festival is a riot. In a riot, as in an authentic festival, prevailing norms of conduct are upended. Boundaries and taboos around private property, trespassing, use of streets and public spaces, etc. dissolve for the duration of the “festival.” This enactment of social disintegration culminates either in genuine mob violence or some cathartic pseudo-violence (which can easily spill over into the real thing). An example is toppling statues, an outright ritual substituting symbolic action for real action even in the name of “taking action.” Yes, I understand its rationale (around dismantling narratives that involve symbols of white supremacy and so forth) but its main function is as a unifying act of symbolic violence. However, this cathartic release of social tensions does little to change the deep conditions that give rise to those tensions in the first place. Thus it helps to maintain them.

I became aware of the festive dimension to riots while teaching at a university in the early 2000s. Some of my students participated in a riot following a home-team basketball victory. It started as a celebration, but soon they were smashing windows, stealing street signs, removing farmers’ gates from their hinges, and otherwise violating the social order. These violations also took on a creative dimension reminiscent of street carnivals. One student recounted making a gigantic “the finger” out of foam and parading it around town. “It was the most fun I’ve had my whole life,” he said. More than any contained, neutered holiday, this was an authentic festival seeking to be born. And it wasn’t safe. People were accidentally injured. A real festival is serious business. Normal laws and customs, morals and conventions, do not govern it. It may evolve its own, but these originate organically, not imposed by authorities of the normal, conventional order; else, it is not a real festival. A real festival is essentially a repeated, ritualized riot that has evolved its own pattern language.

The more locked down, policed, and regulated a society, the less tolerance there is for anything outside its order. Eventually but one micro-festival remains – the joke. To not take things so seriously is to stand outside their reality; it is to affirm for a moment that this isn’t as real as we are making it, there is something outside this. There is truth in a joke, the same truth that is in a festival. It is a respite from the total enclosure of conventional reality. That is why totalitarian movements are so hostile to humor, with the sole exception of the kind that degrades and mocks their opponents. (Mocking humor, such as racist humor, is in fact an instrument of dehumanization in preparation for scapegoating.) In Soviet Russia one could be sent to the Gulag for telling the wrong joke; in that country, it was also jokes that kept people sane. Humor can be deeply subversive – not only by making authorities seem ridiculous, but by making light of the reality they attempt to impose.

Because it undermines conventional reality, humor is also a primal peace offering. It says, “Let’s not take our opposition so seriously.” That is not to say we should joke all the time, using humor to deflect intimacy and distract from the roles we have agreed to play in the drama of the human social experience, any more than life should be an endless festival. But because humor acts as a kind of microfestival to tether us to a transcendent reality, a society of good humor is likely to be a healthy society that needn’t veer into sacrificial violence. And a society that attempts to confine its jokes within politically correct bounds faces the same “uncanny and terrifying” prospects as a society that has tamed its festivals. Humorlessness is a sign that a sacrificial crisis is on its way.

The loss of sanity that results from confinement in unreality is itself a Girardian sacrificial crisis, the essential feature of which is internecine violence. One might think that with little but hurt feelings at stake, online interactions would be less fraught with conflict than in-person interactions. But of course it is the reverse. One way to understand it is that absent a transcendental perspective outside the orderly, conventional realm of “life,” trivial things loom large and we start taking life much too seriously. This is not to deny the substance of our disagreements, but do we really need to go to war over them? Is the other side whose shortcomings we blame for our problems really so awful? As Girard observes, “The same creatures who are at each others’ throats during the course of a sacrificial crisis are fully capable of coexisting, before and after the crisis, in the relative harmony of a ritualistic order.”

Surveying the social media landscape, it is clear that we are indeed at each others’ throats, and there is no guarantee that that will remain a mere figure of speech as something uncanny and terrifying approaches.

About the Author:

Charles Eisenstein is the author of The More Beautiful World our Hearts Know is Possible. His work is now featured on Substack.

Content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Feel free to copy and share.

© 2021 Charles Eisenstein

TOP IMAGE BY PIXABAY